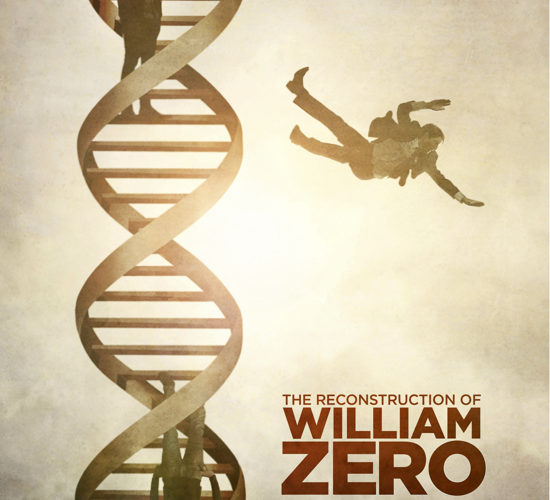

“Life is a whim of several billion cells to be you for awhile.” A genetic researcher utters these words halfway through Dan Bush’s moody indie sci-fi The Reconstruction of William Zero. Most attribute that quote to Groucho Marx, but the film leaves not just the origin vague, but the intent as well; it’s a fleeting, perplexed thought amidst a sea of perplexing thoughts, that on a whim become this film for awhile. Later, Amy Seimetz—playing the protagonist’s ex-wife—draws a starker line in the existential sand with “There’s no moral order to any of this. We don’t get paid back for the pain we went through.”

That pain she is referring to is dramatically sketched in the opening scenes of William Zero, as harried geneticist William (Conal Byrne), in a moment of self-absorbed negligence, runs over his own son, killing him. Upsetting and disarming, that prologue immediately sets the stage for an eerie, often frustrating exploration of the lengths one might go to truly shed the grief and regret of the past. If you’re not sure exactly what subgenre of science-fiction William Zero actually belongs to, then I’ll do my best to not spoil that here. The film has a few meager surprises, but they are worth arriving at on your own, free of too much expectation.

The following can be safely said; William has seemingly collapsed professionally, personally and emotionally when the film picks up in the present. He’s lost his memory after a car accident, and must face anew the painful realities of his life; his wife Jules (Seimetz) is no longer with him, his marriage has crumbled after the death of his son, leaving his twin brother (Byrne again) to help him clean-up the aftermath. It’s also not a giant spoiler to point out that the two Williams share more than a brotherly connection, or that the genetics background both men share factors in greatly with what’s going on. Back at the lab, William is questioned by his superiors regarding vital, missing materials; they fear espionage, theft or worse. As mysterious men start following William around, he himself starts trailing Jules, trying to reestablish a semblance of contact and trust.

The central struggle in William Zero has less to do with the plot itself and more with a warring tension in the film’s tone. The overarching gist of Bush’s film deals with the concept of a man wishing to improve himself in such a way that the hurt life has dealt him can be miraculously washed away. This is a meditative idea, not a visceral one, and the best sequences in William Zero follow Byrne as he attempts to right the wrongs of the past without being overwhelmed by them; pursuing Jules, struggling in his work to find a scientific answer to his present crisis. There’s a deliberate chilliness to the world William finds himself in, and the production adopts a low-key, nearly reluctant tone. We are not edging towards the solving of a mystery, but towards the inner chambers of a man who has been deliberately hiding himself away.

All of this material more or less works, most of it a credit to Conal Byrne as William and his twin. Despite playing a man waylaid by grief, Byrne discovers several different notes to play; the addled scientist, the eternally wounded father, the hopeful husband who wants to save his marriage. Seimetz is sidelined somewhat as Jules, but she does quiet, bittersweet work that echoes her tremendous role in Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color. In its best moments, William Zero strives to be the same kind of science-fiction that Carruth makes; character-driven, concerned more with the mysterious universe of human emotion than the vagaries of its science, and eschewing traditional narrative resolution. Unfortunately, Bush also splices in the worn-out genre remains of old Outer Limits episodes and bad psuedo-science potboilers. There’s a creaky thriller structure that develops in Zero, and by the end of the film, much of the poignant and compelling ideas have been wrestled to the ground by Shyamalan-style hijinks.

Zero is worth seeing, even if it can be occasionally frustrating in execution. To get the gist of what Bush and Byrne’s screenplay is after, you do have to make it through the X-Files style plot mechanics. Still, their central idea has a strong speculative power. The imagery is frequently dreamy and disorienting, expressing William’s emotional distress and the lingering hope that exists to correct it. For once it’s nice to be more intrigued by the scientist’s motivation for the technology than the technology itself. If only Bush had trusted the focal dilemma of his drama before he decided to send in the genre clones. This William deserves better than leftovers.

The Reconstruction of William Zero is now playing limited release and available on VOD.