Nick Simon‘s The Girl in the Photographs seems to be a story reverse-engineered from its final image — which, for a low-budget horror film, is an effective one. No spoilers here, and it wouldn’t matter if there were. By that point, it’s too little and far too late to redeem the film after we’ve been subjected to recycled horror tropes, which predictably clunk their way toward an unsettling final moment. Perhaps this should have been a short and not a ponderous, forgettable feature. In a sense, it’s a horror picture for the selfie generation — fitting, as the narrative is utterly vapid and shallow.

Colleen (Claudia Lee), a South Dakota waitress, begins finding posed photographs of murdered women left at the coffee shop where she works, uncertain if they’re real or staged. They indeed are: the photographers are a pair of deranged backwoods boys who lock women in cages and photograph their terrified faces before killing them. The news story goes national, drawing the attention of acclaimed L.A.-based photographer Peter Hemmings (Kal Penn), who believes the images are inspired by his own work. I assume the name is a film-geek reference to David Hemmings, star of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, an infinitely superior film set in the world of photography, while the killer’s modus operandi brings to mind another classic, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. It’s never wise to draw comparisons to such beloved films, for imitators inevitably fail to surpass their masters.

Similarly, the film opens with two women laughing uproariously as they exit a movie theater. One exclaims, “No more horror movies for me.” Her friend disagrees with, “I thought the first kill was great!” (Incidentally, The Girl in the Photographs‘ first kill is not great. In fact, “great” is not a word that should be found anywhere near this movie.) These lines would indeed feel right at home in a Wes Craven film, which relegates the dialogue into the realm of an unintentional red herring. Within minutes, we quickly realize this is hardly worthy of such comparisons. Unlike cutesy and self-aware ’90s horror hits such as Craven’s Scream, this has no ambitions of satirizing the genre. It’s merely throwaway dialogue, and, like almost everything else in the narrative, it could be tossed away and the plot would continue on undisturbed. Hardcore horror fans may have fun with the goofy characters and morbid premise, but, as the final entry in the great Craven’s filmography (albeit as an Executive Producer), The Girl In The Photographs is a whimper, not a bang.

Craven’s horror catalog is full of tongue-in-cheek moments of levity, playfully toying with the genre’s formulas to often entertaining results. Unfortunately, that was long ago. The majority of the screenplay’s crude attempts at humor drop to the floor like a dead bird, roughly as smart and funny as your average episode of Entourage. Is the idea of mocking superficial, airheaded supermodels at the cutting edge of comedy? (Sorry, Zoolander 2.) Its screenplay contains a laborious jumble of differing tones, which alternately appear and vanish whenever required by the threadbare slasher formula. Thank your lucky stars for Dean Cundey‘s craftsman-like cinematography, which elevates moments to the edge of mood and atmosphere, blinding car headlights cutting through the night and momentarily evoking his earlier work with Steven Spielberg and John Carpenter.

The recent horror films of Kevin Smith come to mind, in particular the woefully miscalculated Tusk, which shares many tonal similarities with The Girl in the Photographs. For starters, the only moment in Tusk that actually works is the closing few moments. In that film, the protagonist played by Justin Long was a crude, self-absorbed scumbag, who meets a terribly gruesome fate. It seemed that Smith believed Long’s character must be established as unlikable before his torture can begin, apparently worried that audiences would not go along for the twisted ride unless the victim somehow deserved it. Instead, by portraying Long’s character that way, we don’t care about him, and thus watch his grotesque transformation with the same lack of engagement until the film’s final moments jump to ephemeral life seconds before credits roll.

If the audience doesn’t care about the characters, they won’t care when they’re chased around or even gutted by psychotic killers. The Girl in the Photographs operates under Tusk‘s same misguided pretense. The hateful big-city stereotypes who descend into this small South Dakota town are really just cannon fodder, fresh bodies for our villain to slice up. There are shades of Tusk‘s hateful lead character in Kal Penn’s acclaimed photographer, clearly based on real-life celebrity photog Terry Richardson and other sleazeballs of a similar ilk: a crass, egotistical chump long overdue his comeuppance. Sure, Colleen seems nice enough, but she’s all surface, seemingly defined by the fact that she has a skeevy ex-boyfriend following her around. They’re essentially meat awaiting the grinder, living bodies ready to be transformed into bloody corpses at a screenwriter’s lackadaisical whim. At least Kevin Smith has the ability to construct nuanced and believable characters, regardless of crudeness. These Los Angeles caricatures are lifelessly one-dimensional, totally lacking any definable or engaging personality traits.

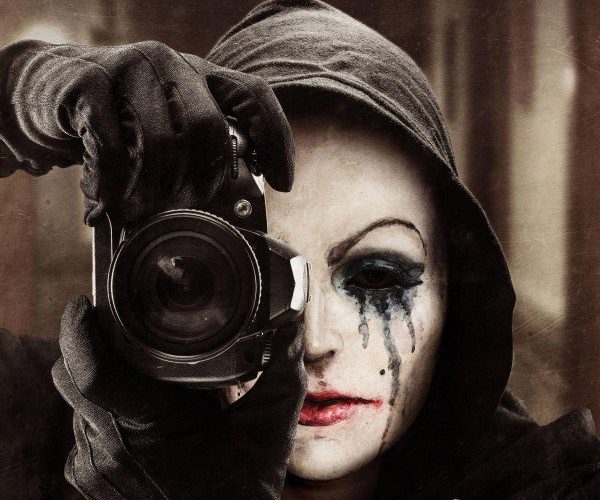

The film rarely builds any level of suspense, mood, or atmosphere, and when it briefly does, the screenplay hasn’t a clue what to do with it. The most effectively creepy scene in the film — in which Colleen is alone in her apartment after her jerky boyfriend departs — manages to achieve a solid feeling of tension for a few fleeting moments. There’s even a fine jump-scare. However, we hastily cut to the next morning and all of the tension immediately evaporates. The “creepy” masks worn by the killers are another wasted element, one the director continually cloaks in shadowy wide angles. Why not let us see these masks, which were likely designed specifically for the production? After seeing Scream, audience members could easily draw that killer’s ghost mask from memory. These details can contribute beautifully to the overall atmosphere, but the film has no interest in such flourishes.

Despite its high-minded ambitions — the film even opens with a William S. Burroughs quote that the screenwriters interpreted rather literally — The Girl in the Photographs quickly devolves into jags of low-brow banality, regularly punctuated by tediously staged violence. Oh, well. At least Dean Cundey was there.

The Girl in the Photographs opens in limited release on April 1st.