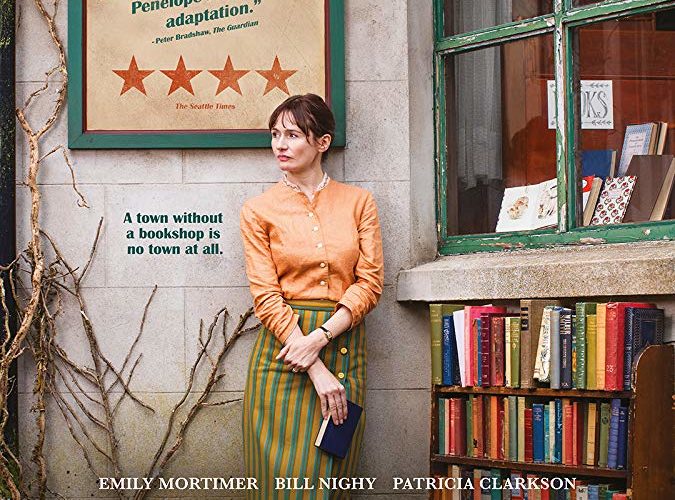

Looks are deceiving with Isabel Coixet’s The Bookshop, an adaptation of Penelope Fitzgerald’s Booker Prize-shortlisted novel from 1978. What appears to be a run-of-the-mill drama that will surely fall into the usual clichés of perseverance and eventual victory about a woman standing up to a small town of bullies that sees her as an outsider is actually much more complex. Rather than be about an ever-increasing contingent of allies coming out of the woodwork to rally around her as she sticks it to the haughty aristocrats up on the hill, this story focuses upon the unfortunate reality that money and power will almost always prevail. Instead of fantasizing about an old-fashioned conservative community’s wholesale ideological change, Fitzgerald and Coixet reveal how success happens one person at a time.

It’s the type of message that simultaneously inspires and frustrates in today’s climate of bullish partisans refusing to recognize how far from reason they’ve strayed. While we’d love to believe hearts and minds can be changed by foolproof rhetoric and empathy, we’ve recently seen too often that truth and decency have become the most rare of commodities. So it will take time to gradually lead each subsequent generation back to shore. It will take educating the young to see past the ingrained ideology of their parents so they can teach that clarity to their own children. Watching Florence Green (Emily Mortimer) refuse to kowtow to Violet Gamart’s (Patricia Clarkson) artificially polite pressure is therefore less important than how she awakens the mind of little Christine Gipping (Honor Kneafsey).

The film hinges upon a notion of remembrance by utilizing narration from Julie Christie to walk us through what happens. We aren’t in the fictional coastal town of Hardborough, Suffolk circa 1959 — this unknown woman is telling us what occurred alongside a wonderful hint of nostalgia. She talks about the widow Florence buying up the derelict, too-long forgotten to dampness and ghosts “Old House” in order to follow her dreams of opening a bookshop as a means to share her love of literature with a community in desperate need of escape, enlightenment, and entertainment. And she introduces the wealthy Ms. Gamart waking from a slumber of complacency with unfounded desperation to claim that “hallowed” site for herself and thus ignite a petty battle led by her over-inflated ego.

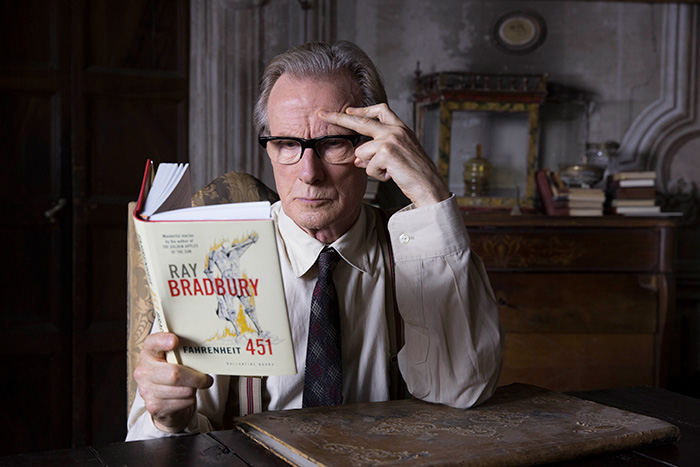

Florence’s business earns surprising customers, young Christine (a vehement non-reader) to lend a hand, and the praise of local recluse Edmund Brundish (Bill Nighy) — a man who hasn’t deigned to communicate with anyone in decades. A colorful mix of characters enter the fray from Florence’s double-dealing lawyer, Violet’s insufferably oblivious husband, Christine’s brusque blue-collar mother, and the educated façade of Milo North’s (James Lance) vapid opportunist. And as the store evolves with an interested if thrifty customer base, the desire to provide them what they need rather than what they think they want arrives courtesy of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Florence’s every step towards progress is met with an attempt at intellectual suffocation by Violet. What seemed a slight melodrama transforms into a treatise on privately financed, bureaucratically sanctioned censorship.

Does it go as far as it could in that respect? No. But that doesn’t diminish its success in subverting audience expectations. Coixet is making a piece of entertainment after all — one that earned Best Film, Director, and Adapted Screenplay at this year’s Goya Awards in Spain. To that end it uses North’s humorous lech and General Gamart’s (Reg Wilson) snobbish detachment from reality to augment the disparity between their charmed lives of leisure and the hardworking citizens down below with comedy. The whole reason Violet wants “Old House” is so she can build an arts center the town doesn’t want. Her inability to accept that a bookshop could help her desire for more culture only proves her intent is purely selfish. It’s a world of out-of-touch caricatures.

This only makes the likes of Kneafsey, Nighy, and Mortimer more interesting by comparison. We laugh when Christine fast-talks Florence into hiring her because of work ethic rather than a love of books and watch as she begins to understand the importance of what those pages hold. We enjoy Mr. Brundish’s awkwardness and lack of social cues to risk dismissing him as a kook only to discover a fiery passion long dormant due to the town’s changing climate into one dictated by its socio-economic divide. And we pull for Florence to find a path through the nonsense and bring back the feeling of community she shared with her late husband years ago. We admire her compassion and kindness all while fearing how they might both facilitate her demise.

That’s a lesson we should take to heart. Yes, it’s blatantly in-our-face here (How often must North tell Florence he’s not a good man for her to heed him?), but that’s not without intention. I might be reading way too much into The Bookshop due to our current political discourse in America, but it’s nice when art can admit civility isn’t enough. Just because we can pat ourselves on the back for not stooping to our opponents’ base level of discourse and morality doesn’t mean it’s an effective strategy for equality. Whereas fairy tales work for children because they still hold onto the optimistic hope of a future untethered by factors far outside their control, adults can’t escape reality. Thankfully some defeats still generate inspiringly potent, long-lasting victories.

The Bookshop opens in limited release Friday, August 24.