I suppose we ought to first get one thing straight: Alain Resnais is one of the greatest directors who ever lived, and Life of Riley is his final film, premiering just three weeks before he passed away at the age of 91. One cannot be blamed, then, for conflating this context with the film itself, particularly given that its structure revolves around an absent figure and, early on, tells us it will build to his inevitable death. Many read You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet, the director’s final masterpiece and penultimate film, the same way, as encouraged by its passing-the-torch theme and a late reveal that one could see as analogous to a life-after-death provided via artistic work.

But Resnais didn’t intend for Life of Riley to be his final film, and he did not die in the making of it or right after its completion, nor does the film itself suggest his own death to an irrefutable extent. (Indeed, there are reports that he was working on a screenplay in the hospital.) The fact is, numerous Resnais films could have been a fitting farewell, so packed are they with wisdom and so strong are their points of view on life, love, and memory; thus, it is the humble opinion of this writer that to read even his true farewell as such is to avoid looking at the film as Resnais certainly would have liked — that is, on its own terms. The director famously told Last Year at Marienbad viewers to simply watch the film and let it take you, the same of which should be said of all his films.

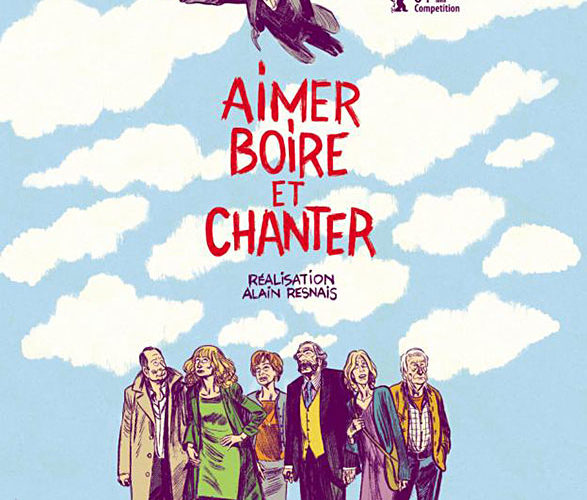

It’s worth noting that Resnais, has almost aged backwards. Landmarks Hiroshima Mon Amour and Marienbad are films made by a man full of wisdom and thought, experienced in love and life, so exacting and masterful in their construction, so deadly serious and grand, that they stood far apart from his New Wave peers. By contrast, Wild Grass is playful, romantic, and vivacious, and now he leaves us with Life of Riley, a funny, energetic, comic-book-influenced film marked by saturated colors, theatrical sets, and middle-aged people acting like the lovelorn leads favored by Eric Rohmer. Admittedly, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet is very much a film about mortality, but one enamored with the act performance — a conflation of art and life that is distinctly youthful. Perhaps he hasn’t aged backwards so much as he has not aged at all, or even needed to. He’s always seemed to possess the traits of both youth and experience in equal parts. In that regard, Life of Riley — equal parts funny and profound — is no exception.

It, like Private Fears in Public Places and Smoking/No Smoking, is adapted from an Alan Ayckbourn play, this one about four friends of George, who has only six months to live, working him into a production of Relatively Speaking (itself an Ayckbourn play). George’s ex and her new partner also enter the picture in somewhat smaller roles.

The core characters are sharply defined: Kathryn (Sabine Azéma, in her tenth collaboration with Resnais) is George’s past lover, a fashionable and fun-loving sort who’s unwilling to let anyone tell her what to do or take advantage of her; her husband, Colin (Hippolyte Girardot), is a doctor who obsessively tries to align all his clocks, an often-times nervous wreck who deeply loves his wife but also drives her crazy; Michel Vuillermoz‘s Jacques (subtitled Jack, as in the play, but pronounced in the French) is a businessman who sits out the production, considers himself George’s best friend, and is busy planning his daughter’s sweet sixteen; and his wife, Tamara (Caroline Sihol, also credited as a co-writer), once aspired to be an actress and now feels a twinge of regret and a pull away from her husband. Monica (Sandrine Kiberlain), meanwhile, left George for Simeon (André Dussollier), but is not so sure about the decision.

George thus ties these characters together. He is who Jacques wanted to be, who Kathryn could have been with, a significant marker of Monica’s past, the successful actor and uninhibited personality Tamara sometimes dreams of, and Colin is the doctor who lets it slip that George is ill in the first place. Though George is never seen, we know him as well as we know any of the other characters. He’s an ideal and a symbol of regret, but also a façade — a hedonist unhinged from real priorities.

Throughout the film, the characters / actors see their performance and life blur together. The first conversation sees Kathryn and Colin discussing marmalade, but she suddenly calls him out on skipping her line. Later, when she talks about going on vacation with George, he asks if she’s reciting lines from the play. “Good,” he responds when she says she isn’t, “because I didn’t recognize a word of it.” Jacques, meanwhile, sees that Tamara and George play the roles of lovers quite well, and begins to worry about the act slipping into reality. It all comes back to George, then. Amidst its riff on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Life of Riley inserts a structuring absence, for one man’s impending death causes his entire intimate circle to second-guess their lives, confront their own mortality, and feel as lonely as George certainly does, given his refusal to put himself in front of the camera.

Greatly enhancing the effect is the film’s aesthetic. Every scene, especially exteriors, clearly take place on a soundstage, with painted curtains standing in for walls, colors slightly but noticeably saturated, and the camera often placed in the “audience position,” so to speak. New locations are announced with comic-book drawings, and whenever a character talks honestly and introspectively, they are transported into a new space for their close-up, one marked by a black-and-white cross hatching. When they finish speaking, continuity returns and other characters respond, but they often seem to say the wrong thing or miss the point altogether. They are all alone on the inside, constantly trying to see beyond the artifice — if that’s what it is — that surrounds them. Life is beautiful, sure, but doesn’t it all look a little… constructed? George is the antidote to that, someone idealized as being so much realer and ideal that he cannot even be pictured amidst the literally-constructed life that surrounds his friends.

This artifice, reflected in the lives of the characters, is manifested in Riley’s unwritten rules. To name a couple obvious ones, there are two unseen characters in addition to George: Jacques’ and Tamara’s daughter Tammy, as well as Peggy, who is staging the forthcoming play. Additionally, almost every scene (excepting a key confrontation) is an exterior. But these are not limitations. Among the greatest delights in Resnais’ final film is how he selectively breaks these rules, continuing to allow his film to expand at the seams, never more than in its unexpected finale.

Things are funny and delightful, sure — both to the characters and to us — but wouldn’t it be great if there was more? Wouldn’t it be great if this were serious and heavy, a Resnais film that could leave big impressions and serve as a memorable, daunting farewell?

In Love Unto Death, Resnais’ first Ayckbourn adaptation, a miraculous resurrection prompts a couple to change their way of living to something more enjoyable, and death prompts questions of what to do going forward. Life of Riley, then, is the opposite: a story of how impending death prompts re-evaluations and externalizes regrets rather than aspirations, and how mortality brings clarity rather than confusion. It may not be quite as revelatory as that film, but it does present a surprisingly complex tale in what, on the surface, is third-rate Shakespeare. Underneath, Life of Riley is far more than meets the eye — it’s been a while since a comedy that could probably float with a family audience has packed so much punch.

Above all, Life of Riley is an ode to living and love, the grim spots of which serve as a carpe diem proclamation without being preachy. Resnais once remarked, “I hope that I always remain faithful to André Breton, who refused to suppose that imaginary life was not a part of real life.” If one must view Life of Riley through the prism of Resnais’ death, this quote of his — so eloquent in its perfect phrasing and full of wonder in its implications — must come with it. Life of Riley’s deliberate rule-breaking plays as surrealist, as if new dreamscapes are being unveiled and entered — but the film, moreover, refuses to suppose that imaginary life does not impact real life. Breton would surely be proud. Farewell, Mr. Resnais.

Life of Riley is playing at NYFF and will be released on October 24, courtesy of Kino Lorber.