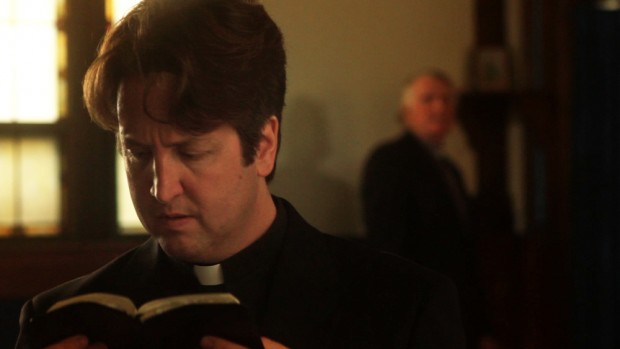

Writer/director Todd Rohal‘s latest film, The Catechism Cataclysm, is a genuine discovery. Quirky doesn’t begin to describe the film, which despite some wackier elements, is more of a comedy than anything else. The Christian-tinged farce about a priest and his idol going on a canoe trip is downright hilarious. The social awkwardness of Eastbound & Down‘s Steve Little carries the film as his idol Robbie [Robert Longstreet] tells many stories-within-a-story that continually deliver laughs. All of it is capped with a perfect song about God f-cking you up if you do bad things. Yes, it goes there.

When I got the chance to interview Rohal I had to jump on it and below you can find our conversation. We touch on the oddity of the title, the crazy stories within the film, how it all started, what kind of freedom he had, the involvement of Kickstarter and the support he received, and even the cameras used in the film.

The Film Stage: Was that on purpose [the title]? Were you trying to make a tongue twister?

Rohal: [Laughs] With the title, when we were making this, it just felt like, let’s make something that maybe somebody finds in the back of their closet after their grandfather passes away. Like some DVD that’s buried back there and they find it and 50 years, 70 years from now they put it in and its…“where did this thing come from?” It just felt like we were making something that was very specifically for an audience that just connected directly to us and our sensibilities. That title just kind of came and it felt like, this is totally unpronounceable and totally unmarketable, no one’s going to be able to read it. You know? That feels like what this movie is. It’s going to be a little confounding but like, those who see it might be intrigued and want to explore it a little bit more.

I was reading that the first film you directed, you actually toured around with it. Not because you necessarily wanted to, but because that was the only way to get the film played.

Rohal: That movie [The Guatemalan Handshake] was right when everything was kind of going to shit in the distribution world and we shot 35mm anamorphic and I had one print made and just decided it has to get shown. I didn’t feel like we can just put it on DVD and send it out. And it just felt like, to me, that theatrical booking thing, I totally got it. It’s just such a totally hard world to enter, but it felt useless to have this print and show it a couple of times and just let it be. So I just started calling theaters and booking them myself, and it worked. It was very easy. Very few people turned us down. Because we would say, “we’re going to show up, we’ll bring some musicians with us, or do something. We’ll get people out. We’ll put the work behind this. And regardless, I think that’s what is. If you have a distributor on board with you or not, that’s what you need to do anyways. You need to work just as hard on that aspect of your film, especially on this kind of level. So it just worked. I mean, it paid my bills for a year and a half; I just toured around with it. And it was not necessarily what I wanted to do, but it opened a lot of doors for me; opened my eyes to a lot of things and the reality of how things are and what people really connect with. What they’re actually out there, looking for, outside of the festivals.

With talking about this film, specifically, in the last few years, there has been quite a shift towards video on demand. It takes it out of having to have a theatrical release. Having to have some other method of distribution. It puts it, literally, right in people’s homes. Are you thankful for that? Are you a hardcore theatrical release kind of guy? What’s the feeling there?

With talking about this film, specifically, in the last few years, there has been quite a shift towards video on demand. It takes it out of having to have a theatrical release. Having to have some other method of distribution. It puts it, literally, right in people’s homes. Are you thankful for that? Are you a hardcore theatrical release kind of guy? What’s the feeling there?

Rohal: No, I think that varies film to film. I felt like, with Harmony Korine when he did Trash Humpers, I felt like that movie was the perfect…I feel like that’s not a theatrical movie. I feel like that’s a movie you want someone to invite you to go see in somebody’s dirty garage.

[Laughs]

Rohal: And you walk into it and you feel like, “What is this?” Are we watching some kind of snuff movie…that’s how that thing plays. I don’t have think that’s the kind of movie you want to see at the New York Film Festival. Like, seeing it with a bunch of snobby people from the Upper West Side, that’s… [laughs] not the viewing experience of that movie. There are certain things that I discovered, like getting a VHS copy of Pink Flamingos from my friend’s dad in high school. And watching that like at 2AM in their living room and just feeling like we were part of some underground cult, finding this thing. You know, you just felt connected to it in that way, in a more personal way. I think there are certain movies that lend themselves to that and sure, maybe they work better from a theatrical sense. Sometimes just having it as your own discovery is important. So however people can kind of get their hands on certain movies is important. But then again, there are certain aspects of a film that are much more of a cinematic experience. You just want to see them on the bigger screen for aesthetic reasons or whatever. Just discovering a movie like Troll 2 or…

[Laughs]

Rohal: I saw Sleepaway Camp for the first time, and it’s just like, “Whoa!” You’re just connected to this group of people that all have that same sensibility of “I saw this movie, I got it at Blockbuster.” I watched it when I was like 14 and totally stuck with me. And you know, there’s certain things that just play better in a more intimate atmosphere.

You’ve talked a little bit about how the film came about, but what was the initial kernel idea?

Rohal: Just a nugget of an image that came to me. I was moving from New York to Austin, Texas, and I was kicking around ideas and it was like, “Oh, look. What about a priest and communes, lost right at sunset” and who would I cast? I had this huge cast that I put together and it was just too big. I just kind of sat on that for a couple of years. And then when I was actually driving back from Austin to New York, a year and a half later, I thought about the idea again, “How can I scale this down? It seems interesting.” And I kept coming back to it and I really wanted to write something for Steve Little. The ideas just started to come together. I guess four or five different pieces I had been kicking around at that time. How can I put all these elements together and have everything work together? The main thread of it was just that story about the crisis of faith for him. And avoiding the obvious jokes of being a priest. Like, let’s obviously not make him a child molester. Let’s make him a guy that’s in a situation I can relate to. And then see where it goes from there. And then I kind of wondered what if people could show this in churches and have a movie about losing faith and returning to it. Returning back to his calling in life. How messed up would that be if that was his testimony. So it’s just stuff like that where the idea really kind of percolated and then came together relatively quickly.

And you talked about how Steve Little was your guy for this movie. You wrote it kind of with him in mind. How nervous were you when you initially approached him?

Rohal: I’d met him earlier when I had written this other script that I took to the Sundance Lab and we had a reading in LA and I asked Steve to be a part of it. I had known of him through the Eastbound and Down crew. I had actually asked him to come on board for that because I wanted to meet him. He came out and read for it and he was really funny. And I was asking him what he was up to and he was not somebody that someone was writing lead roles for at the time. I had just kept that in mind and called him up and said, “I wrote this thing for you. Do you have any interest in doing it? It’s about a priest that drops his bible in a toilet.” He said he called his mom up and was just like, “Hey, I don’t know, does this sound funny to you?” and I guess she was laughing about it and said, “Yeah, you should do that. Sounds pretty funny.” So, we got to work. And very bluntly, Steve had never been a part of anything like this. The first day of shooting he’s just like, “So, none of these people are getting paid?” He was so confused.

[Laughs]

Rohal: Like, “If I was a sound guy, and I got paid for my job, why would I come out here with all my gear and work for you for free?” He had never witnessed anything like this before. And slowly, I could see it dawning on him and it was like, “OK, yes. I can see they’re really behind it.” It’s a very different atmosphere than working on more studio, local things.

Yes, definitely different than HBO. I’m curious. There was this crazy story about this guy in a hotel with a misfiring gun, and I’m just curious, what was the inspiration for that?

Rohal: I wrote a short story maybe a few years before, and I just had it there and didn’t know how to fit it in or even what movie it fit into. It felt like this little short film about a guy who fails at everything and even his own suicide he couldn’t execute properly.

[Laughs]

Rohal: And we were like, “You know what? This feels like the stuff I should have written in high school.” [Laughs] It’s funny, when I was writing it, I though this is going to be one of those terrible suicide stories people writes in high school. So, I filed it away. And when this came up, I need a story that is kind of interesting but seems like somebody wrote in high school and then they just never did anything with. And then I remembered that and sifted through all my writings and found it again. I kind of wanted the story to ring like something like a high schooler would write where they’re touching on something that’s kind of inspirational, but it’s not very good. [Both laugh] Something you can see someone else getting a kick out of, for some reason.

How much freedom did you have with this film?

Rohal: Complete. This was in response to me turning in another film that I had been trying to get off the ground for years, and I had just gone through so much of this process of just talking about, ‘Well, why can’t you do this?’ or ‘Why can’t you do that?’, or ‘How would that work?’ and it was constantly questioning, and questioning, and questioning it to the point where you don’t even know what you have anymore. And my friend Rob [Longsreet], who is in the movie was talking to me and I just found out I thought this movie was going to go, and it ended up not going, ‘You know what? Someone just needs to write you a check for something and tell you yes. That’s what you need to hear at some point in your life. If you need my help, I’ll do it. I’ll write the first bit of money to make this thing happen.’ From that process, and the crazy thing is, no one said no ever again. Every time the phone rang, good news just constantly coming in for this. It was forever that forward momentum of just people saying, ‘Yeah, this seems completely nuts. I don’t fully understand what you’re doing, but let’s go for it and I just want to see what comes out of it.’ It was a complete support system. The same thing with Rough House, when they came on too. I sent a picture of Steve dressed as a priest in front of a picture of Jesus and he wrote back to me about how they could get this thing going. They never read the script. They saw it when it premiered at Sundance. So it was just blind support, top to bottom. For better or worse. [Both laugh]

With freewheeling it as much as the budget is concerned, I also noticed that you actually got involved with Kickstarter to get the last half of the production? Kind of push over the edge?

Rohal: Yeah. It was right before we shot and we just needed a little. I mean, we had so many crew people come on that wanted to work on it, it was like this big Seattle contingent of crew members that were willing to do this between the lulls in productions over there and it sounded like a lot of fun. So we actually had enough people, we just needed money to help house them and pay for their food and the extra equipment we could get. But I was just really hesitant to do it. If we announce that we are making this movie, then people are going to know we are making something. My whole operation from the get-go was that it would suck if we failed, but no one would never know that we made it and just bury it. As soon as we announced that we were making something, it became a reality and people would know that we made something, but we had to do it. It was too much to turn away and we raised the money really quickly. That really came through and worked. I was really surprised how that stuff actually works.

It’s like, “OK, I’m going to announce it on the internet and it isn’t even made yet.” This could be a complete and utter disaster. I thought that was also kind of funny that you got an incredible amount of support. You were asking for $6,500 dollars and you ended up raising well over nine grand.

It’s like, “OK, I’m going to announce it on the internet and it isn’t even made yet.” This could be a complete and utter disaster. I thought that was also kind of funny that you got an incredible amount of support. You were asking for $6,500 dollars and you ended up raising well over nine grand.

Rohal: You know, I’m the same way where I don’t even look at what they’re making, I support who I like. If it’s from a certain filmmaker, I just want to see their next movie. I’m the kind of person that wants to go into a movie and not know what it is, you know? If something is good and someone says, “You’re going to like this,” I don’t want to know anything about it. So, seeing what the production was like on some levels, sure, that’s possible. But I think a movie like Demo or Cory McAbee‘s Stingray Sam…

[Laughs]

Rohal: I would hate to see that go through the process of questioning that. You know? It’s like, that has to come and be a raw voice, just straight out of their head. And to make those kinds of things to look like they do and work like they do, the weirder the better.

What kind of equipment did you use?

Rohal: It was just two borrowed Canon 7D cameras with these lenses we rented, I can’t remember what they were, but we shot with two cameras pretty much the whole time. Super minimal lighting package. And then, Ben Kasulke, our DP, got the wrong hazy lens filters for it or something, and we were about to send them back but we put them on and it made it look more…shitty. You know if you have older 16MM lenses and they’re all scratched up? In film school you’d see any bright spot just turn into this haze around it, and it just felt more like an older horror film. It felt like Friday the 13th or something. I loved that. I loved that as we were looking at it, we were like, ‘Yes!’ It was a bit worse than I thought it would be but it takes away that weird crispness of what those digital things look like. The luck of our outdoor locations and the way the lights hit just made our film feel more like a horror film and it really fit into what it became.

The Catechism Cataclysm is on VOD and in limited theaters.