It took fifteen years of perseverance—acquiring the rights, losing them, and reacquiring them at the behest of screenwriter Jane Goldman stoking the fire—but producer Stephen Woolley finally got Peter Ackroyd‘s 1994 novel on the big screen as The Limehouse Golem. There were some big names attached from Merchant Ivory originating plans to Woolley hoping for Neil Jordan years before developing it with Terry Gilliam. Don’t let this taint your opinion when peering upon Juan Carlos Medina‘s name on the director’s chair, though. Despite being only his sophomore feature, there’s a lot to like as he imbues the proceedings with a nightmarish air of mystery and suspense. It’s a dark Sherlock Holmes-esque case bolstered by a heartfelt desire for justice exactly when it appears impossible to find.

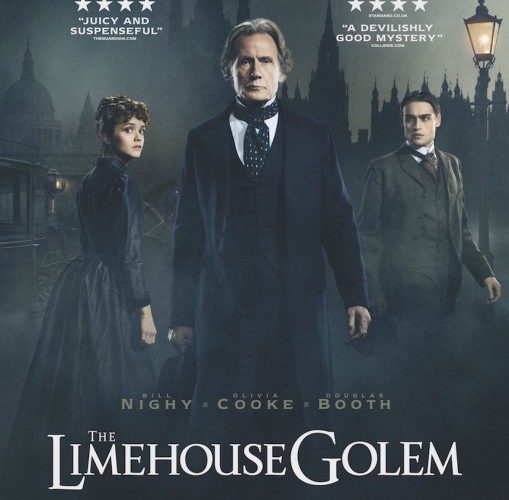

Like the words uttered by music hall comedian Dan Leno (Douglas Booth), this film begins at the end with the death of John Cree (Sam Reid). Found by his wife Lizzie (Olivia Cooke) and their maid—the latter seemingly with a bone to pick—Constable George Flood (Daniel Mays) has no alternative but to arrest the former as his prime suspect. It’s a straightforward opening that ultimately proves to be anything but, the ordeal marking a potential conclusion to a serial killer’s rampage as well as Inspector John Kildare’s (Bill Nighy) auspicious introduction. Assigned the Golem case as a scapegoat with prized policeman Roberts (Peter Sullivan) coming up empty for too long, Kildare cultivates his own fascination in Lizzie. She may just become his star witness.

What occurs from here is a complex yarn woven by Ackroyd/Goldman to keep us guessing. Everyone has a secret whether rumors of homosexuality, childhood abuse, or temper hidden beneath a façade of chivalry. Kildare is lost until a fateful epiphany whisks him off to the library where he and Flood discover a diary positing the Golem as one of four men: Karl Marx, George Gissing, Dan Leno, or John Cree. It’s the type of revelation that provides hope where none existed previously—and not just for Kildare’s career either. After speaking with Lizzie, the inspector can’t help but feel a responsibility to save her. If he can prove John was the madman wreaking havoc throughout Victorian London, her presumed guilty verdict would render her the city’s unwitting hero.

Before we approach the future, however, we must first engage the past. This entails a fun loving yet tragic tale of “Little” Lizzie’s musical career under the tutelage of Leno. Our menagerie of characters increases with actress Aveline Ortega’s (María Valverde) jealousy, theater owner Uncle’s (Eddie Marsan) proclivities, and aspiring playwright/hanger-on Cree’s ambitions. Accidents happen, the show goes on, and tensions rise to a fever pitch as details of each horror clicks with Kildare to shrink his list of suspects down. When not learning of Leno’s circus or the Crees’ involvement within, the inspector vividly imagines each murder described in the aforementioned diary. Like Hannibal‘s Will Graham, he sees and hears these heinous acts performed with cold desire by each probable culprit via a demonically deep and knowing voice.

A heavy darkness falls upon the film that I did not expect. These murders are viciously bloody, the text with the Golem’s distinctive “M” going into grave detail about each stab of the knife. Humor is also involved courtesy of Kildare’s intrinsically no-nonsense attitude creating involuntary sarcasm and Leno’s troupe’s profession, but the latter arrives shrouded beneath a layer of deflection hiding the deep-seeded pain Dan and the others use comedy to combat. If not for the rapport between Nighy and Mays, The Limehouse Golem could easily become too dour for the accessibility necessary to invest in the search. Kildare’s earnest quest for truth needs Flood’s personable nature to bounce off as well as Lizzie’s victim to force him into solving the case as rapidly as possible.

The script carries us through without much effort, its expertly paced discoveries keeping us enthralled despite early assumptions pointing to Cree as the titular monster. With that certainty comes the acknowledgement a twist may be in the works—it too an obvious conclusion arriving as soon as the thought manifests. What makes Goldman and Medina’s film potent is realizing the killer’s identity is unimportant. Kildare’s job is to ensure there won’t be any more victims, but our interests concern the living not dead. Will Lizzie’s life be spared? Will Kildare’s opportunity as lead inspector pan out? And what will happen if these two discover the truth to be something far more sinister than believed? We assume Kildare will find his man, but what he’ll do next is the kicker.

Credit Medina for never wavering from his nightmarish aesthetic of darkened streets and splattered blood. Mays shines as the everyman; Cooke a woman concealed beneath layers of artifice constructed to survive her past. Valverde’s catty adversary to Lizzie adds some humorous bite while Booth memorably brings Leno to life through flamboyant theatricality and precise humanistic compassion trumped only by the old adage, “The show must go on.” But it’s Nighy who carries the whole despite only joining the project after Alan Rickman’s failing health forced him out. I can envision Rickman relishing the role with a Severus Snape sneer, but Nighy’s nuanced, confident professionalism may suit it best. Kildare needs to be an unwavering boy scout so that the impossible decision presented at the climax earns its weight.

The Limehouse Golem is currently playing at the Toronto International Film Festival and opens on September 8.