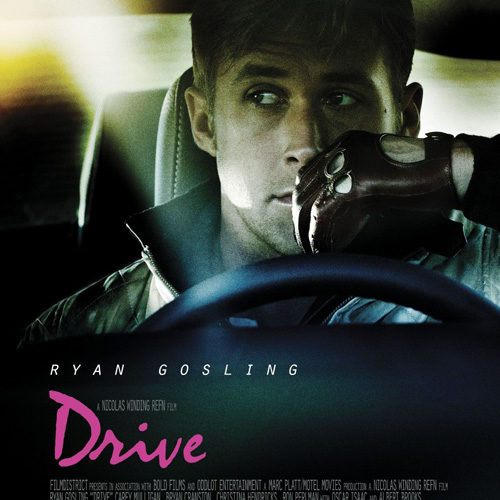

“They just don’t make ’em like they used to.”

It’s our go-to reaction whenever we feel the need to rue modernity. This catch-all derivative statement can be applied to appliances, cars, and especially movies. Which is exactly what makes Drive such a pleasure: they don’t make movies like this anymore. And in many ways? They never did.

This is both exciting and limiting. Drive is firmly in the mold of a late-70s/80s action film, in its plotting in characters. It plays every archetype to the hilt, relying instead on the phenomenal cast to carry the emotion while we check off our scorecards.

Ryan Gosling gives a dynamite performance as a character known only as Driver. He’s not just any driver, naturally: he’s the best. All of his jobs go through Shannon (Bryan Cranston), an automobile shop owner looking to go legit, taking his gifted wheelman onto the race track. The dream is bankrolled by the film’s dual heavies, the former producer Bernie Rose (a phenomenal Albert Brooks) and the constant thug Nino (big, loud, abrasive Ron Perlman). Everything is going according to plan until Gosling runs into Carey Mulligan‘s Irene, a single mother so fragile if you blow hard enough she’d shatter to pieces. Her husband (and the father of her child) returns from jail, but an outstanding debt thrusts Driver into a deal that–shockingly–goes bad.

While the plot is at best full of tropes, and at worst rote, the direction from Nicolas Winding Refn is snare-drum tight. The script from Hossein Amini, adapted by James Sallis‘ novel of the same name, is well-paced but incredibly sparse. Take, for example, a scene in the first third of the film where The Driver is supposed to woo the girl. It is played not as a bumbling, unsocialized man endearing himself to the girl. He simply has no words to say. And so they gaze at each other, deeply, for a minute, maybe longer. And through the extraordinary talents of Mulligan and Gosling, and the absolute guile of Refn to try and pull this off in a film with a ton of excellent action beats and car chases, we have a touching, poignant moment written, ever so subtly, through the tiniest of facial twitches. When she leaves, we know he has her because she has showed us.

It is a refined film when it needs to be, giving us a more humane side to these characters than we have any right to ask for in this kind of genre. It’s a beautiful film when time warrants, as cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel turns Los Angeles into a neon dreamland, caught somewhere between modernity and a 1980s that never quite existed. For every moving bit of silence, there are loud bursts of gun fire, splats of blood, and the rippings apart of human flesh when hit with a shotgun blast in close proximity. The tone is rather flexible (there are some great one-liners from Brooks and Perlman, which is probably to be expected) but the action becomes way too heavy for my taste as well as my logistic meter.

We meet Driver when he’s on the road, on the job. After picking up two bag men, he plays a tense cat-and-mouse game with the local on-duty police. Soon a helicopter–and its spotlight–hovers over head, announcing to the world that the non-descript car has now been sighted. As the perps (and the audience) squirm in their seats, nothing more than a frown flashes across our hero’s face as he hits the gas and dominates the curves of the greater Los Angeles area. After a good number of minutes, Driver makes off into the night, ready to go home and add another mark to the “last day litigated” countdown he keeps at home.

The entire sequence is predicated on the ever-present police force that he must constantly avoid. Soon after, we are treated to a gaggle of murders that take place in sleezy motel rooms, restaurants, and busy parking lots with nary a single “whoop-woo!” let alone a physical officer of the law getting involved. All the while Driver, initially so concerned, never gives concealment or consequence a thought.

For that reason (and the entire Driver character, really) this might be the best superhero movie of the year. That is not meant to be a slight. There is something wonderful about watching a character who does everything well, especially in the underworld. There is seemingly nothing that Gosling’s character can’t do, and to watch his actions play out really is a joy to behold. If, for whatever reason, we haven’t christened him a star yet, then this is the movie that should push him over the top.