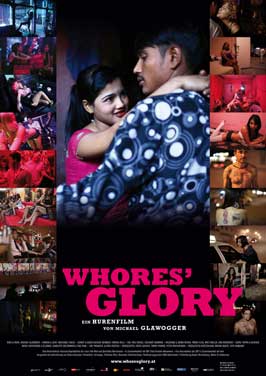

Concluding a trilogy that goes places even Mike Rowe of Dirty Jobs could never go (not on a basic cable anyway), Michael Glawogger’s Whores’ Glory is lucid, exotic and heartbreaking, tracking the world’s oldest profession in three segments from Thailand, Bangladesh and Mexico. The film is fascinating yet problematic: instead of hiring actors as some filmmakers choose to do, Glawogger hires the folks he has been documenting to participate in recreations of their lives (a scene in Mexico is the most obvious). He’s done this since has been since employing drug addicts and hustlers in early Giuliani-era Times Square to recreate prostitution related robberies in Megacities.

Glawogger’s two previous features, Megacities and Workingman’s Death, are heavily aestheticized, the “traveling filmmaker” has a background amongst other things in experimental film. Whore’s Glory opens in hyper-real Bangkok – prostitutes dance high above the city on a bridge, shooting laser beams downwards to attract clients at “The Fishbowl,” an establishment that displays the women behind glass. They get by on two clients per session and live what I’d consider a middle-class urban lifestyle unlike their counterparts in Bangladesh, which implies (without giving ages) the existence of child prostitution. At “The Fishbowl” the women debate giving up their jobs of sleeping with married men and foreign travelers (for which they have certain national preferences based on how hard they’ll have to work, so to speak – to keep it PG for this site).

In Bangladesh’s brothel district, called The City of Joy, that is the last thing apparent. The system is controlled by women (although the landlord is never seen) and designed to enslave generations of women in the system. Herein contains several of the saddest moments, but Glawogger explains a sex worker he spends time with in Megacities is one of the happiest people he’s encountered; she enjoys her life. He doesn’t go in search of her when the film moves to The Zone, a strip dedicated exclusively to prostitution in Mexico.

The role of religion is heavily on display, at least in The Zone and The City of Joy. Glawogger treats these contradictions with great respect. Life in The Zone is harsh and it’s implied drugs, alcohol and superstition fuel it. Whore’s Glory is an aesthetic treatment, not entirely different than HBO’s American Undercover series, as it allows its subjects a voice and they are collaborators with the filmmaker. The aestheticization is seductive in its use of music (including many tracks by PJ Harvey), brilliant narrative style compositions and editing, and staged moments that potentially blur a line between documentary and ethnographic narrative. This may be a complaint amongst viewers but it understands the limits of documentary. From the outside these lives look harsh and this is an experience that aims to draw us in — to share both in the joy, hardship and glory — resulting in one of the year’s best films.