Six year-old Aslak (Adam Ekeli) lives a quiet life with his single mother Astrid (Kathrine Fagerland) in a rural town adjacent to farmland and a mountaintop forest. He’s too young to understand all that’s happening around him — especially considering he’s generally told to keep away from the adults when they’re speaking — but he knows enough to gauge the strained atmosphere and heavy emotion growing. So he looks through keyholes and gazes out windows, everything he sees simultaneously meaningful and yet without meaning. When things get too intense he hides in his closest. When he begins to feel alone he finds his dog Rapp. And as tension mounts at home (police chatter about his estranged brother puts Astrid on edge), a monster begins lurking in the distant trees.

Let’s put “monster” in quotes because the word is used more as a concept than literal manifestation of the supernatural as far as Jonas Matzow Gulbrandsen’s film Valley of Shadows is concerned. Or is it? The result of his and Clement Tuffreau’s script always being from this young boy’s perspective means it could be anything. Maybe the vague generalizations he hears the men whose sheep are being slaughtered speak are in response to a lone wolf feeding in the night. Or perhaps the folk tale conjecture of his older friend Lasse (Lennard Salamon) about a werewolf skulking in the light of a full moon is more than just a scary story born from heavy metal music and active imaginations. Maybe Aslak’s brother is this suspected beast.

What is it that he knows and what can he not comprehend? Try and remember back to when you were six and attempt to answer that question because it won’t be easy. We like to think we had a handle on things in the comfort of hindsight, but who’s to say our current brains aren’t simply deciphering the puzzle pieces we couldn’t fit together back then? Imagine yourself a scared kid who doesn’t know where his brother is — who can’t even begin to recall what he looked like or who he was with Mom locking his bedroom door. Now your friend is showing you mauled animal carcasses and illustrative engravings of werewolves feeding on children. Wouldn’t you conflate the two? Dual unknowns caught within a fantasy mirroring real life?

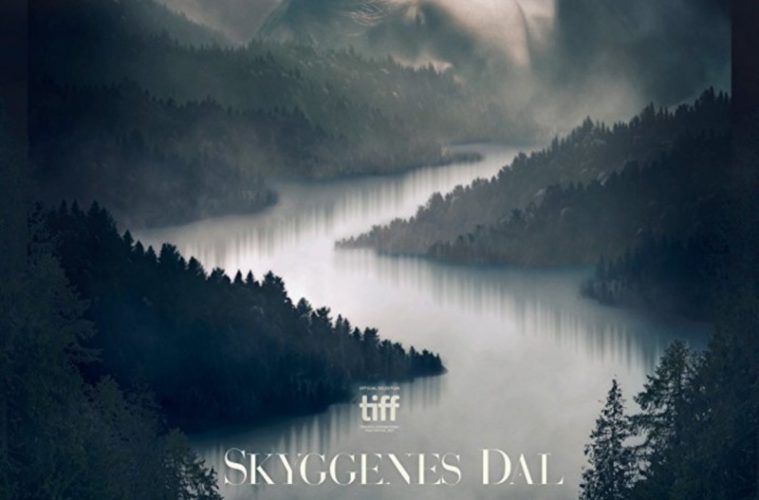

With these dark thoughts set against Zbigniew Preisner’s haunting score, you’ll discover yourself teetering on the edge of reality and nightmare. Gulbrandsen lets this visual and aural aesthetic envelop us by removing dialogue from most of the runtime either through distortion caused by distance or Aslak’s isolation. Music fills our ears as the fog rolls in to turn an already fairy tale forest dwarfing anyone who comes near — and cinematographer Marius Matzow Gulbrandsen ensures we experience its scale — into a mysterious region holding werewolves and moose alike. But while Aslak’s first foray across its border abruptly ends in fright, his second cannot. Rapp is missing and only he can find him before the monster. Couple that horror with an emotionally retreating mother and Aslak would officially be alone.

The film is a subtler take on the concept seen in A Monster Calls with both searching to represent grief’s manifestation in a child. Whereas that film dealt with an adolescent in his teens (or soon-to-be), however, Valley of Shadows takes us even younger to highlight a mind too fresh to be anything but impressionable and confused. But we aren’t merely watching Aslak’s journey while fantasy sequences arrive with clear delineating features separating them from life. Gulbrandsen has instead put us in his shoes by placing the camera at his level to peer around corners and watch without listening. We receive the same details as Aslak, our brains parsing fact from fiction with a realistic lens the filmmaker might not be using. Therefore anything remains possible.

So don’t be embarrassed when you hear something heavy in the distance cracking branches. Don’t think you’re the only one holding your breath when the camera zooms into those trees to find the culprit. We fear what we cannot see just as Aslak does, our imaginations conjuring the worst possible outcome as a product of the creepy environment and tense psychological air created. And when a stranger (John Olav Nilsen) is seen watching us from across a river, how could we not expect to witness a transformation of some kind? We’ve simultaneously traveled deep into this dangerous forest and into Aslak’s constantly roving mind so that every little thing becomes real and unreal. It’s impossible to discern one from the other as fear renders our direct vision untrustworthy.

In this regard it’s recommended that you enter Aslak’s world knowing as little as possible so your mind can process events without preconceptions. Bask in the mystery of not knowing whether Gulbrandsen has made a poignant drama or a bona fide horror because the two don’t have to be mutually exclusive. The film doesn’t need to embrace those genres literally for their labels to be apt either, the mood and tone our wonder absorbs proves as relevant as seeing something concretely fantastical onscreen anyway. Gulbrandsen isn’t telling a story, he’s leading us through one with all the uncertainty necessary to question, interpret, and understand despite no true answers being provided. Whether a monster is murdering those sheep is inconsequential to the existence of one blocking Aslak’s path.

Valley of Shadows premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.