A love letter stuck in limbo—forever undelivered, returned to sender, and lost in transit—the union between Layla and Qays can never be cemented. Caught in a world of oppressive forces from both occupiers of their land and the zealots perverting their religion, these two college students must contend with tradition in a generation ready to move forward. Theirs is a time where a Palestinian should be allowed to enjoy a film such as Rocky without being called a traitor or ally of the Zionists. In 2001, art should stand on its own as a way to live and breathe away from the stifled dreams of an anger-ravaged Gaza Strip lost and unable to find its way home.

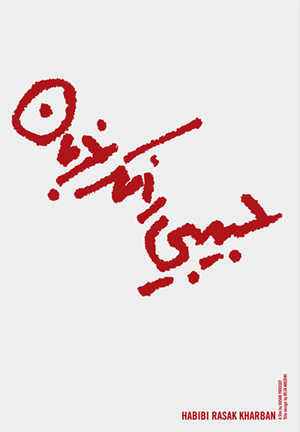

Written and directed by Susan Youssef, Habibi Rasak Kharban [Habibi] is a contemporary retelling of the ninth century tragic love poem Majnun Layla. Legend has the work written by a poet driven mad by his love in what’s now Saudi Arabia, but the universal themes fit right in with the tumultuousness of Gaza at the turn of the century. Youssef uses its words to fashion a story of fearful and confused young men who use the Qur’an to inflict the same harm on their people as they accuse the Israeli occupiers of doing. Clouded by family history and the warped teachings of Hamas, they are recruited through their grief for fallen friends, the unknown origin of bullets flying around perfect fodder for cultivating an enemy to revile and blame. It’s a place that frowns upon progress, making the love between a beautiful girl of means and a construction worker refugee impossible.

Bookended with poetic verse—opened by Qays (Kais Nashif) and concluded by Layla (Maisa Abd Elhadi)—we watch the journey they take towards their inevitable realization of how far freedom has fallen from favor. Attending school in the West Bank, he for literature and she engineering, life seemed hopeful and bright. They spoke of brilliant Arab minds from the past and the time devoid of art afterwards as their people were displaced. To them, though, such physical and psychological imprisonment shouldn’t be an excuse to stop creating, but at least those living through it found a way to preserve the greats from the era now long distant behind them. The time before Israeli occupation survived so that in theory it could never be forgotten. Yet with the new regime of hate, it ended up being lost anyway. Artists no longer had a place in the new war, fighters ruled by using words of peace and love against those who cherished them the most.

As Layla says towards the end of the film, the Qur’an was always about tolerance. Her parents quoted it to share its beauty, not to police and punish as the emblazoned power of youth usurped it to mean. She and Qays are the most Muslim people in Gaza, their love for one another stronger than any force. They don’t need to be inspected by bullies or steered into unwanted life choices. The occupation of their land pushed their studies back and left them unfinished and without work, so using this lack of education to make Qays an undesirable husband in the eyes of Layla’s parents (Yosef Abu Wardeh and Najwa Mubarki) only gives the Israelis victory. And they understand this fact after seeing the love their daughter has, but love isn’t enough. Her wellbeing and future rest in marrying a self-sufficient man that can provide for her—this and nothing else.

So Layla and Qays must meet in secret, their hope for love all that’s left to cling to as they seek an escape. She attempts to return to school while he tells the city of his muse through graffiti at night—stonewalls of Gaza standing amidst the rubble becoming the blank canvases of his soul. She yearns to return home with him to the West Bank, their time at school more powerful than what she has with family. But his painted poetry risks driving them apart forever as it sullies her name within a culture that rejects public affection. Her parents hasten their plans for matrimony as a result and throw Qays out of their house while Layla’s brother Walid (Jihad Al-Khattib) and his new friends look to teach him a lesson.

Forbidden to be together, one last chance to begin life anew presents itself. With it comes the difficult choice of forsaking all she believed before the moment she first heard her Qays read aloud. Love becomes an impossible decision between happiness and survival, the physical and the spiritual forking away from each other to never again meet. To run away means going against the Qur’an and falling pray to western ideals—a leap that’s harder than it may look from the outside. Their anguish and sudden realization of what’s most important give way to the inherent tragedy of growing up with customs that have refused to modernize in a world no longer able to shield the alternative lifestyles available abroad. Elhadi and Nashif give their all to the camera, opening our eyes to the political and emotional oppression onscreen and earning Habibi’s spot at the Toronto International Film Festival as a film to let us experience a lifestyle we may never fully understand.

Engrossing us with her three-dimensional characters, Youssef shows a wonderful handle on tone. But clumsy moments throughout rush certain plot devices and sadly show the artist’s hand behind the desired authenticity of the poetic verse on display. The reason for Layla’s brother’s newfound allegiance to Hamas is abrupt and easy, people changing their outlooks do so unnaturally to serve the story, and the resolution slaps us in the face before we know what to do with it. And while this tale of Romeo and Juliet needs such a forceful climax to resonate and earn its dénouement, something about it seems manufactured. Like Layla and Qays’ love in the story, the resolution isn’t enough to support the whole. Those moments that do work, however, will captivate and grab hold as you follow the central, tragic bond until its end. It is here that we are all released into the sea—the singularly place where freedom rules and one’s duty is to the heart alone.

Habibi plays at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 14, 15 & 17.