Just when you think it can’t get worse—that the vocal, racist minority spewing bile will be extinguished in a show of tide-turning empathy—everything is literally engulfed in flames as a city watches it burn to cheers from a cesspool of hate. This is the 2012-2013 season for Beitar Jerusalem FC in the Israeli Premier League. A soccer team beloved by enough fans to make them a political target for President Reuven Rivlin and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the reason their owner at the time (Arcadi Gaydamak) bought the club was to cement his (failed) bid for mayor. The only team in the league to never sign an Arab, their diehard fans (La Familia) earnestly and joyously chant, “We’re the most racist team in Israel.”

Documentarian Maya Zinshtein couldn’t have picked a better season to shoot a movie about Beitar. Four years removed from playoff conversation while Gaydamak ignored his financial responsibilities to shore up bad investments on other fronts, this was to be their return to form. And the victories did add up with their star goalkeeper Ariel Harush leading them to the pitch as close to thirty thousand fans screamed from Teddy Stadium during home matches. Those championship trophies lining caretaker Meir Harush‘s Beitar museum at the clubhouse were itching for a new addition and it appeared the moment was approaching. Gaydamak was back in the box, goals were being scored, and it looked like nothing could stop them until a “friendly” in Chechnya appeared on the schedule and changed everything.

Born out of Gaydamak’s business contacts to entice Chechen Republic leader Ramzan Kadyrov into joining his ventures, the nil-nil game was stated to be a huge success by the owner. The players didn’t necessarily care either way. They got a match in, saw a new country, and were headed back home. So no one could imagine what happened next: Beitar signed Chechen defender Dzhabrail Kadiyev and striker Zaur Sadayev. The season was halfway over and suddenly there were two new players, a development that probably wouldn’t have caused much of a stir except for the fact they were Muslim. And this is a very crucial distinction to make. They were Muslim, not Arab. So technically Beitar remained the only “pure” club. But try telling that to La Familia.

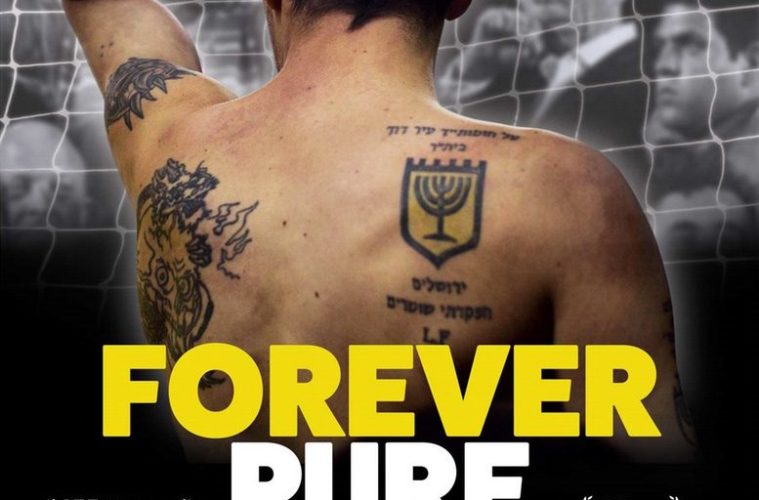

Zinshtein’s film moves from a document on the rise of Israel’s most infamous club to an exposé into the nation’s systemic racism. Entitled Forever Pure as a reaction to the banner depicting those words in the stands, we begin to understand exactly what Beitar means for its fans and Jerusalem on the whole. Heroes are labeled traitors overnight, team chairman Itzik Korenfine begins to receive death threats, and talk about the vehement protesting being sparked by “a vocal few” turns out to be as far from the truth as humanly possible. Soccer becomes a breeding ground for vitriol and abuse as being a fan proves a dangerous proposition for all. Kadiyev and Sadayev are left on an island unto themselves, morale plummets, and the losses mount.

It’s unbelievable what happens and thanks to Zinshtein’s cameras it’s captured in its entirety. Social media plays a role as well as government officials while the signs that this uproar was brewing for years and years amidst chants of “Kill the Arabs” come out of the woodwork. But no one cared back then. Everyone turned a blind eye because none of Beitar’s line-up of foreigners was Arab. The city let their racism and bigotry grow because the politicians relying on these fans’ votes needed them as a unit. And when the few become the many there’s nothing you can do. As soon as you change your position to try silencing them, they turn on you too. The comparison to Trump’s America is simply too uncanny to ignore.

Beyond anything that happens on the field, this story becomes irrefutable proof of a system relying upon prejudice. It doesn’t matter that what La Familia is arguing about isn’t even true—logic and sense don’t factor into their emotional power to tap into humanity’s darkness. Callers on the radio try to justify the hate by saying, “If you wouldn’t let your daughter marry an Arab, why would you let one on your team?” Not only are the two young men not Arab, Beitar isn’t the fans’ team. It is Gaydamak’s to do with as he pleases. The only thing fans should worry about is winning or losing, but as we soon discover these followers couldn’t care less. To them a failed season is reason to declare them correct.

What happened proves a dangerous precedent that the epilogue’s “where are they now” text admits no one learned. Zinshtein gets every epithet, slur, and violent altercation on camera as well as the silence of teammates save Ariel Harush, Dario Fernandez, and Ofir Kriaf (two for the side of morality and one his own egocentric drive for professional security). With so many political documentaries on the scene over the past five years, you wouldn’t think a movie about a soccer team could reveal itself to be just as crucial to conversations on oppression. One could say this is even more important because war and rebellion breathe this type of nationalist hatred. To see it happen over a sports team is to acknowledge just how bad the situation has become.

Forever Pure premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.