What if humanity’s apocalypse wasn’t the world’s end? We’ve become so used to treating ourselves as rulers of this planet despite knowing so little about it and the surrounding universe while also doing our best to destroy everything we touch. So what are we truly besides another in a long line of species with no greater hold on Mother Nature than the last? Our demise doesn’t therefore have to be by our own hand and hubris. Perhaps those two things merely place our heads on the chopping block for fate to enter. Instead of hoping to survive a viral zombie outbreak, maybe we should welcome it as an earned necessity. Instead of fighting tooth and nail to stop our demise, maybe our death ensures Earth’s continued life.

In this way the last line of young Renata’s (Amy Schuk) prayer as remembered by her sister Vivi (Gro Swantje Kohlhof) is true, “We are but rocks that see both life and death.” And we should aspire to be exactly that: spectators living amongst equals in a carefully modulated ecosystem rather than empowered creatures who believe we hold the right to deem what should or shouldn’t survive within it. Because when you think about it, why would God be ours? Why would God be in our image if not for our needing that familiarity for our own sense of self worth? We are but a blip on the timeline of history that arrived well past the universe’s creation. We’re just another piece of a grander entity. Ants marching.

But just as we need God to look like us, so too must our heroes in order to feel empathy. Is that a strength or weakness for our species, though? If Carolina Hellsgård and screenwriter/comic creator Olivia Vieweg have any say via their film Endzeit – Ever After, it’s most assuredly the latter. Because what does that human-centric thought process create? Entitlement. It allows us to decide who is good and who isn’t — who should survive and who shouldn’t — but not on a macro scale like our system of laws would pretend. No, we decide those answers on an individual basis. We point out those amongst us that will be a liability and we dismiss them. We scoff at the weak and inevitably become haunted by our own weakness.

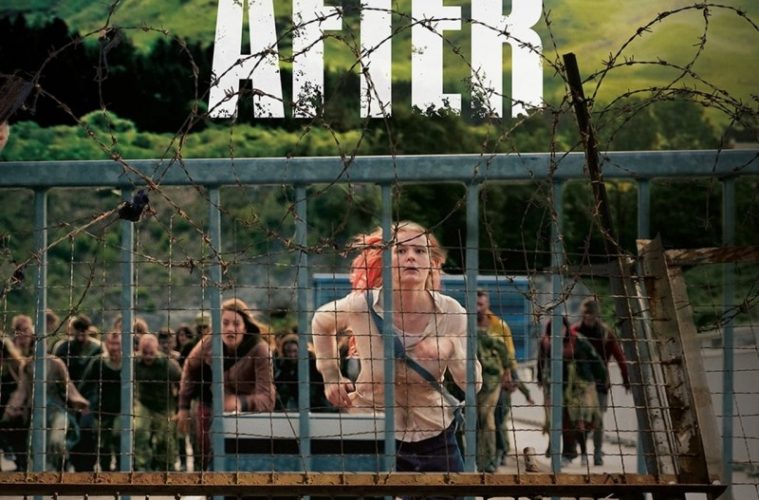

To teach this lesson they supply us one of each: the coward (Vivi) and the so-called warrior who represses her fragility (Maja Lehrer’s Eva). They place them in a world where only two cities remain, both fenced off from the wide-open expanses now ruled by the undead. One is said to be developing a cure while the other refuses to afford such hope and merely disposes of the infected with a utilitarian swiftness. Vivi and Eva live in the latter and it can’t help but gradually dismantle an already flimsy resolve that’s miraculously stayed intact these past two years post-outbreak. One is followed by the nightmare of being unable to save her sister while the other’s job is to remind everyone else that no one can be saved.

So while the road to their mutual destination is different, they both seek escape for the same reason. The hope is that this sister city can provide optimism where home supplied dread. Maybe if they can arrive at a place that still values life as more than a ticking time bomb forever quickening to zero, the voices and visions of the horrors they’ve endured might evaporate from memory. But whether they acknowledge this similarity or not, they’ll be forced to at least understand it by the end once their mode of transportation leaves them stranded with nowhere to run. Will they hold the other (or tragically themselves) as expendable? Or will they realize their self-inflicted isolation is what’s kept them drowning? Only together do they stand a chance.

What makes Ever After so intriguing is how Hellsgård and Vieweg put these familiar characters and ubiquitous premise into a mythology that’s wholly unique. The rabid zombies feverishly running for flesh here are still changing. What was human is turned inhuman and then it becomes overgrown with weeds as if the Earth is reclaiming its failed experiment. And if that’s the case, has survival as we know it been rendered the wrong choice? We’re so used to projecting ourselves as Icarus flying too close to the sun that we forget just how inferior we are to so much around us. What’s ironic is that those same people who believe man is king are the ones who believe we’re too insignificant to cause climate change. It’s hypocrisy at work.

Well either way Mother Earth is angry and threatening to consume every single one of us with natural disasters and disease. And in a stunning example of even greater irony, we are that disease. We are allowing Measles newfound life. We are helping to facilitate the creation of super bacteria. We are shifting nature to our financial whims with no regard for the future. So rather than simply wipe us out, Mother Earth has made it so we see our true selves first. She strips away the façade in order for us to become rabid beasts with no impulse other than consumption. But she also shows us the strength to fight back — just not in a way that will achieve victory. She lets us reclaim our dignity instead.

Here’s where this beautifully shot piece of horror becomes undeniably beautiful. Amongst the carnage and evil lies a beacon of light. Perhaps it’s Vivi and a guilt that’s strong enough to make her contemplate suicide before ever wanting to replicate what she did to earn it. Maybe it’s Eva and her capacity to feel remorse and strive for better regardless of the gruff exterior she uses to shield her vulnerability. Or it could also be the God-like creature known as The Gardener (Trine Dyrholm) — proof of what’s to come and/or a delusion presenting what’s always been here despite our ceaseless attempts to ignore it. If we’re to believe in the flood and the rapture, why not believe in this? In each scenario mankind disappears. Our privilege runs out.

Endzeit – Ever After screened at the Toronto International Film Festival.