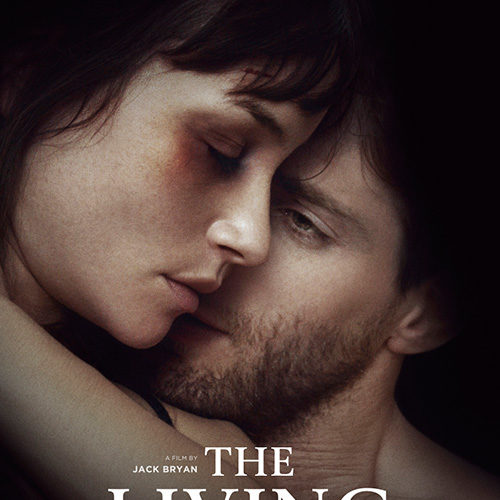

An interesting choice was made on Jack Bryan‘s film The Living—one that occurred before the camera rolled. If you’re familiar with Fran Kranz‘s emotionally fractured science nerd Topher from Dollhouse and Kenny Wormald‘s coolly confident Ren from the Footloose remake, you’d probably have a pretty good idea of who would play who inside a plot dealing with an abusive husband and the sheepishly insecure brother-in-law wrestling with the desire to hire a hitman to kill him. For whatever reason—and this is to the filmmakers’ credit—the opposite proves true. While Kranz’s capacity to earn our sympathy via guilt shines through whenever his Teddy’s attempts at charming battered wife Molly (Jocelin Donahue) into forgiving him fail, all remnants of Wormald’s cocky dancer have been replaced by a surprisingly effective turn as the apprehensive Gordon.

I didn’t think he had it in him, but Wormald steals The Living back from a marketing campaign using Kranz as its poster boy. It’s a smart move on paper, however, despite the character of Teddy being the first person we see and his actions the impetus for all that follows, it’s Gordon who receives the majority of the screen time and the heavier workload. I wouldn’t quite say the domestic abuse subplot is marginalized as a result, but it’s definitely not given enough room to allow Molly’s decision to let Teddy stay seem more than the emotionally clouded choice her mother Angela (Joelle Carter) believes to be true. Their final interaction at the fridge does the conversation no favors either.

Perhaps this was Bryan’s intent: to show legitimate remorse on behalf of a man who doesn’t remember the heinous act he committed beyond its evidence and the impossible tug-of-war she undertakes as a victim refusing to be made the fool or relinquish the love and life she’s built before portraying the sobering truth that good intentions aren’t enough. If so, he did a great job ensuring this dark thriller becomes even darker by quickly transforming a moment of relief into one of anguished disappointment courtesy of a smile and shrug of indifference at the potential of restarting the cycle of abuse all over again. This dynamic between Teddy and Molly could fill out a feature film of its own, but by having it become the background to Gordon’s tale unfortunately makes it appear rushed and incomplete.

As Gordon’s hired gun Howard (Chris Mulkey) states—and the title so succinctly alludes—evil isn’t left to those caught on the receiving end or any deity intently watching from afar that refuses to intervene. It’s the living who endure the pain and suffering, the bystanders witnessing it who are unable to forget. This is the role Gordon plays as a young man talking big with friends yet unable to find that same voice with those who matter. The film ultimately becomes his—how he reacts to what’s going on, how he decides to intervene, and how he reconciles his own actions no matter how extreme, misguided, or poorly executed they are. Whether his sister takes her husband back is meaningless in the grand scheme once Gordon marks him a dead man. Their relationship simply impacts his conscience.

To some extent it impacts ours too because we see Teddy and Molly’s evolution through the unfiltered gaze of flies on the wall. Gordon and Angela have their preconceptions, their ideas of morality and the line where enough has proven enough. But they don’t see Molly wielding her strength and forcing Teddy into a position where he must earn redemption. Her cold shoulder may thaw too rapidly due to constraints of the medium and runtime, but we understand she isn’t rolling over or placing the blame on herself. There’s a fantastic scene wherein she makes him take her to dinner at their usual haunt with everyone they know in attendance. He not only must own what he’s done with her, but the whole town too. From there her forgiveness is hers alone to give.

Both Kranz and Donahue perform their roles nicely, giving their nightmare a necessary emotional velocity even if the script doesn’t quite give us anything we haven’t already seen before. The captivating part of The Living therefore comes from Gordon trying to escape the anger trapped inside his head and find the courage to do what his mother wishes he would where defending his sister is concerned. Mulkey’s Howard adds a lot to this by being drawn as a complete wild card of which we can only rely on his lack of humanity. We in the audience watch as he helps nudge Gordon along, making our own assumptions on whether Teddy deserves the future these two men are laying for him or not. We watch Gordon struggle with the reality of what’s coming and how his bark morphs into bite.

Through it all, however, Wormald retains his uncertainty. He possesses an innocence that’s quickly relinquished with one phone call—an innocence replaced by fear. Gordon becomes a master at avoiding eye contact as though he is hiding from everyone because he cannot hide from himself or his failings as a brother, a son, and a man (or at least those the people around him have projected). Whether Teddy, Molly, or Howard survive the ordeal or not, their fates are in Gordon’s possession. Life or death, love or hate, forgiveness or blame—Gordon is blind to them all above this sense of duty. Portraying that tumult isn’t an easy feat and while the film may end up exactly where you know it should, Wormald keeps it resonant by becoming worse than the men he’s seeking to expunge.

The Living is currently touring the festival circuit and screens at Austin Film Festival this weekend.