James Wan’s new horror movie, The Conjuring, has all the accoutrements we expect–the declarations of truthiness, a beleaguered family under spiritual attack, and long, gracefully rendered scenes of people sauntering around in the dark while something damp and clammy silently glides over their shoulder. Unlike previous features, Wan is in full amusement park mode for this particular haunting and his performers are ready to exercise—or is it exorcise?—their considerable acting chops.

Wan and scriptwriters Chad Hayes and Carey Hayes (adapting the House of Darkness, House of Light trilogy) have the benefit of an actual 1970’s setting for The Conjuring and it does wonders for the film’s visual ambience. When Carolyn (Lili Taylor) and Roger Perron (Ron Livingston) and their girls move into their new home in Harrisville, Rhode Island, site of old ghastly wounds and some supernaturally oozing fresh ones, the house itself becomes an eccentric, unpredictable character. Production designer Julie Berghoff and art director Geoffrey S. Grimsman create a convincing melding of tingling neo-Gothic architecture and moody 70’s kitsch. Shot through with psychic dread by the discerning, transformative lens of DP John R. Leonetti, the spaces of the house adopt their own other reality, a world easily shared by sloppy teens, harried parents and lonesome specters without the audience batting an eye.

Sketching out otherworldly terror with a modest, restrained hand, Wan uses the first act to set the stage for a horror movie that depends upon our emotional investment, which is always a tricky maneuver because it requires all cylinders of the film be firing in unison when the ectoplasm finally hits the fan. The way this is done is not necessarily original but it is effective; Wan takes us into the headspace of the children living in this house, sisters who react with a dramatic honesty when dark figures start showing up in the corners of their bedroom and sinister messages start manifesting in uncouth ways.

Taylor and Livingston are called upon to deliver a married couple whose strain and devotion can be understood without the need for extrasensory event, the kind of chemistry and rapport that could carry a film even if phantasmal monsters never showed up to menace them. Wan and his writers are not merely borrowing a page from Poltergeist, they lift the entire early structure. Unlike Insidious, which more or less just copied and pasted the same source without artistic intent, The Conjuring makes these tropes its own and Wan has learned to more expertly walk that tightrope between what creeps us out and what just takes us out of the picture.

There is a refreshing reliance upon old-fashioned minimalist scares in the movie, and it trusts the power of well-placed, meaningfully eerie props. Two hands clapping from the darkness is pants-soilingly terrifying in a way that a CGI Darth Maul clone never was in Insidious. The mood and trajectory are established skillfully and early, and we fear for this family–who are in some dire straits if this attack continues—well before the movie introduces Ed and Lorraine Warren to us. If there was any element of The Conjuring I was particularly aware of, and resistant towards, when walking into the theater, it was the use of the real-life Warrens and their status as self-proclaimed demonologists to sell the film as “true.”

To judge The Conjuring on its own merits, any feeling one may have towards the Warrens and their vocation (The Amityville Horror is also based off their case files) should be left at the door. Those who believe them to be self-deluded frauds or some canny breed of con artists will likely be as reluctant to embrace the film as the true faithful, who think the Warrens were God-appointed Catholic warriors fighting hell spawn, will be to dismiss it. None of this really matters because despite the claims of truth, The Conjuring is a fantasy that exists firmly in the same world that all Hollywood supernatural horror occupies; one filled with malevolent forces that do everything in their power to be muddy in intent but disruptive in practice. There’s a reason this lot always have unfinished business; they suck at clarity and subtlety.

The good news then is that Patrick Wilson and Vera Farmiga are so effective that they sculpt characters who feel real and plausible while not seeming especially connected to the actual Warrens. Wan has likely chosen the duo because the image they perpetuated—questions of authenticity aside—is enticing, a committed couple who battle the supernatural as an earnest family unit, resting upon the rich and already established vault of Catholic tradition to draw formidable villains from. What the Warrens give us in this film is an equal calibration to the besieged Hayes clan, and their subplot works in tandem with the already stirred pot of a family in crisis. On all sides of the haunting, there are people to care about and they carry the film beyond a simple entertaining exercise admired for its funhouse string pulling.

To my surprise and delight, The Conjuring is a memorably spooky event; a campfire tale told not just with reliable bells and whistles, but also with a breathless adamancy that stirs the hackles and attacks the imagination. If it all goes on too long and achieves an anti-climactic resolution, these flaws can be forgiven because they are attached to a film that is full of juicy spookiness, signaling the evolution and maturity of a genre director who has finally shed the shackles of Saw.

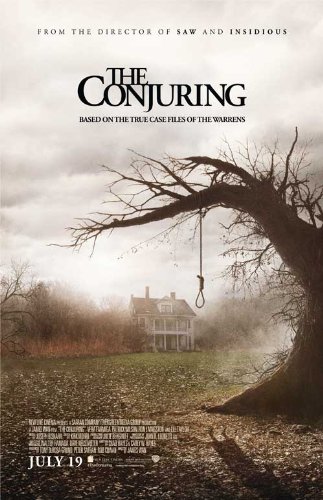

The Conjuring opens in wide release this Friday, July 19th.