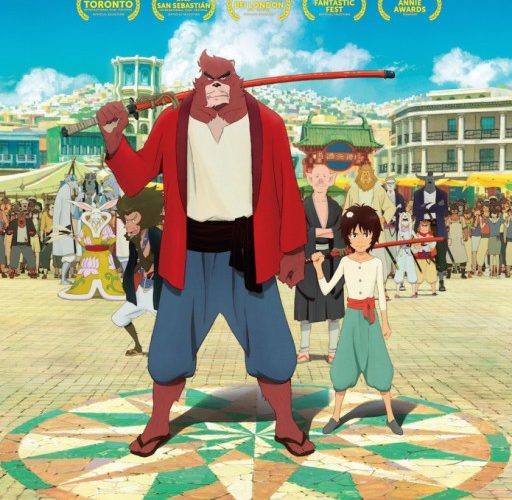

Two worlds collide once young Kyuta (Shôta Sometani) and warrior Kumatetsu (Kôji Yakusho) meet in Mamoru Hosoda‘s The Boy and the Beast. The former was recently orphaned after his mother’s death (she had divorced his father years ago and her family refuses to get in touch with him), currently working his way towards becoming a solitary street urchin full of dark rage aimed at the human race for causing him such pain. The latter is a candidate to replace the Beast Kingdom Jutengai’s lord—a fighter of immense power but little discipline who probably won’t stand a chance against his opponent Iozan (Kazuhiro Yamaji). One needs a father and the other an apprentice. One to learn strength and love while the other discovers humility and patience’s immense value.

It’s all pretty familiar—at the beginning. The film’s first half can get tedious as a result. The human world has forgotten Kyuta and the beast world sees Kumatetsu as a joke. They’re the perfect pair because they’re so alike: two stubborn creatures that should amplify the other’s volatility to further separate them from their goals and yet somehow prop the other up for victory instead. Everyone dismisses them as lost causes including Kumatetsu’s best friend Tatara (Yô Ôizumi) and an animal monk-in-training named Hyakushūbō (Rirî Furankî) who’s taken a shine to the boy. But if Kyuta can learn from Kumatetsu despite his master’s complete lack of educating talent, they can grow together as one. Their fire can begin fueling their desires rather than hold it back.

What follows is your run-of-the-mill fast-forwarding through training as eight years pass and visible changes occur to both characters’ physique and mental integrity. Tempers are still high, but a mutual respect has blossomed where only frustration existed. I admittedly started to get bored because nothing seemed intriguing beyond the inevitable conflict between Kumatetsu and Iozan once out-going Lord Sōshi (Masahiko Tsugawa) finally set a date (he must first decide what God to ascend to in retirement and meanwhile work his sage wisdom to make his favorite scoundrel of a pupil mature into the potential leader he knows him to be). Well, nothing but the very obvious artistic decision to render one of Iozan’s children as human. How does no one else see that Ichirōhiko (Mamoru Miyano) isn’t beast?

The truth will eventually come out and luckily the journey to that revelation isn’t left stagnated by Hosoda’s initially ho-hum origin tale of master and apprentice. Suddenly, just when I thought the film would languish in that trope forever, a wrinkle is introduced. Kyuta rediscovers the alley to the human world and enters it. This one action catalyzes a wholly different fork in the road to conjure themes of parenthood (biological versus adoptive), pride, love, friendship, contrition, and emotional stability in the face of so much chaos. The Boy and the Beast literally becomes something new and better as Kyuta transforms from a pawn in Kumatetsu’s game to a three-dimensional character ready to confront the tumultuous life he has lived. The praise I had read finally made sense.

Importance changes as the yin and yang of human and beast rises to the surface to show why the inhabitants of Jutengai were so fearful of Kumatetsu taking on a human apprentice. Cool anime aesthetic choices such as the darkened silhouette of a boy with a hurricane void of black where his soul should be earn meaning beyond visual flourish. Bullies become cheerleaders; sportsmen with impeccable form become villains possessed by greed and envy. So many relationships colored with primary hues transform into complex rainbows of uncertainty as gamesmanship is threatened and traditions defiled with the toss of an unsheathed sword. Jutengai is revealed to be a glimpse of Earth without war—a utopia man swiftly seeks to refashion in his genetically predisposed violence and unnecessary death.

I’m not saying the film didn’t work before this shift; it simply didn’t resonate beyond an adolescent level of humor and storybook evolution. That isn’t a bad thing considering American audiences will consist of families with children who want to experience exactly that (there are a couple instances of Kumatetsu saying “shit” in the subtitled version, so maybe the English dub alters the translation). Adults need more so it’s nice to discover the rather somber introduction to Kyuta’s (then known as Ren) tragic existence is foreshadowing and not exposition to never be mentioned again. Those years following spent in Jutengai training just don’t possess worthwhile stakes since it’s practically a fairy tale dream. Hosoda needs a dark streak of drama and he delivers it right on cue.

This is true with the animation too. The style isn’t necessarily inferior to Studio Ghibli—it’s just different. While the matte paintings are gorgeous (one scene renders a chain link fence behind Kyuta and Sumire Morohoshi‘s Choko as though photograph), the characters are less elaborate. It’s more Pokémon than Spirited Away—a personal preference, I know. But once the shift in plot occurs to add drama, the visuals change as well. Telekinetic powers of destruction show themselves, monsters are created, and cheery disposition is replaced by uncertainty. Good becomes evil and both worlds are at risk of never being the same again. And all of a sudden Kumatetsu’s quest to defeat Iozan and Kyuta’s refusal to be weak prove inconsequential as personal desire is replaced by selfless heroism.

The Boy and the Beast opens in limited release on March 4th.