American journalist Marie Colvin’s family’s lawyers say they have evidence proving the Bashar al-Assad-led government of Syria ordered her death in 2012. If that doesn’t express the power of a free press, I’m not sure what could. At a time when the US President is acting like an autocratic leader deciding who is allowed to cover the White House beat while also calling the media at-large “an enemy of the people,” we would do well to look back at what Colvin did just before a Homs explosion killed her. Back then it was still believed that Assad was bombing terrorists rather than civilians and she risked everything to tell the world he was lying. Her voice opened eyes and her coverage turned the spotlight onto its true target.

It’s therefore tough to see how little has changed in the six years since. Assad still bombs his citizens (see Last Men in Aleppo) and America still ignores it by banning Syrian refugees. This truth doesn’t diminish what she did, though. If anything it reinforces how important it was. Because whether or not the current administrations of countries with the resources to do something about this atrocity will, people with the potential to unseat them now have the tools to right the ship. War correspondents like Colvin who put themselves in the path of bullets to tell the stories of those without the means to do so are literally the first line of defense for victims of crimes against humanity. And Syria was far from her first rodeo.

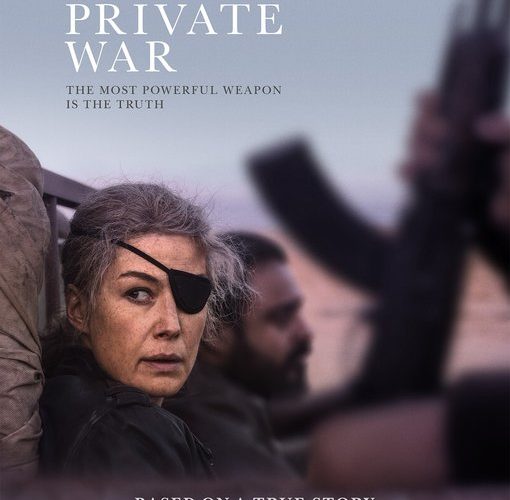

Enter documentarian Matthew Heineman and his narrative debut A Private War. Based on a Vanity Fair article by Marie Brenner (“Marie Colvin’s Private War”), screenwriter Arash Amel delivers an eleven-year countdown before Homs to get into the mind of Colvin and attempt to better understand her drive and demons. Heineman then takes us into the war zones of Sri Lanka, Iraq, Libya, and Syria to reenact the danger and suspense of what embedded journalists go through on a day-to-day basis. He must go even further than that, though, as Colvin (Rosamund Pike) wasn’t your run-of-the-mill reporter looking to broadcast just close enough to the action to make it seem real. No, she would ignore the military’s instructions and head out without protection. She was a moth to a flame.

Eleven years is a long time to depict in two hours, but Heineman and company do well to accomplish it by refusing to linger on sentimentality. This isn’t some manipulative drama looking to ram its message down our throats because it’s harrowing enough to simply let it play out. So we watch as Colvin shirks protocol and loses her eye in the process. We experience the uneasy slips into nightmare as her PTSD-ravaged brain permanently affixes the horrors she’s seen onto her emotions until she begins to see a dead Palestinian girl lying in her bed. There’s the heavy drinking, the angry ex-husband, and the worried friends (Nikki Amuka-Bird’s Rita shines brightest) who aren’t afraid to tell her she’s gone too far despite knowing they can’t stop her.

Save a couple brief excursions to awards ceremonies that cut before speeches and really only arrive onscreen to reinforce Colvin’s matter-of-fact nature and business-first mindset, Heineman puts his focus almost exclusively on the cost of her job rather than its rewards. He doesn’t gloss over the cynicism of wondering whether there will be enough humanity left to care about the things she has exposed. He also doesn’t try to pretend coping with war is easy. Not only is Colvin shown having debilitating episodes of traumatic memories, she seeks help and inevitably comes out of it too soon or goes back into Hell too hard. But she wouldn’t have it any other way because she knows no one else would be willing to go that extra mile.

That is the title’s “private war.” When everyone is told to run, Colvin heads in closer to make sure those poor, helpless casualties aren’t forgotten. It’s why her The Sunday Times editor Sean Ryan (Tom Hollander) sends her to locales she believes are being underserved and why he can’t ever be certain she’ll get the job done before finding herself strapped to a hospital bed or worse. So it’s hardly surprising that Paul Conroy (Jamie Dornan) would ultimately become the one photographer she actually likes being that he served in the army, knows first-hand what’s at stake, and is almost as fearless as she. Even he can only be the voice of reason half the time, though. The other half has him following so she’s not forgotten either.

This film is concrete proof that doing so is impossible. Its snapshots amidst chaos and destruction become the perfect setting for Colvin’s psychology, motivations, and contradictions to be laid bare. We don’t need more with her ex (Greg Wise’s David Irens) than his inability to accept that what she does is more than just a career to understand that chapter in absentia. We don’t need more than her later boyfriend Tony Shaw’s (Stanley Tucci) smile or a heartfelt kiss atop her sightless eye to understand the stability and love he provided. And after hearing her tell Conroy about all her regrets, we see that they will never overpower her desire to ensure she never creates more where her innocent subjects caught on the battlefield are concerned.

These inferences become fact through Pike’s magnificently inspirational performance. Heineman places her inside nightmarish environments and she handles each with a compassionate humanity and justifiable rage that we sadly don’t see enough of these days. Her tenacity will force us to take note of her actions, but it’s her vulnerability that exposes the woman behind the legend. She’s so fully committed to this role that the actors around her can’t help but give their best through sheer reactionary impulse. There’s a scene with Hollander towards the end that highlights his internal tug-of-war between being friend and boss that will remind you he has the goods for more than his usual comic relief. And Dornan shedding his Christian Grey sociopathy to become her brother-in-arms can’t help but stand out.

Part of why the performances work so effectively is that Heineman uses his documentary sensibilities to capture them with sensory context above dialogue alone. It’s almost as though he filmed three times the amount of footage we see and chose to edit it in a way that augments the whole rather than each solitary moment moving from A-to-B. Those interactions back home with friends work to give depth to her joy and pain. The ones that occur in the field lend substantive evidence towards her personal mission to get underneath the politics and write the truth. Heineman progresses through the years with purpose as far as showing Colvin’s relationship with war above all else. Rather than straight biography, A Private War proves an emotionally poetic representation of identity.

A Private War is now in theaters.