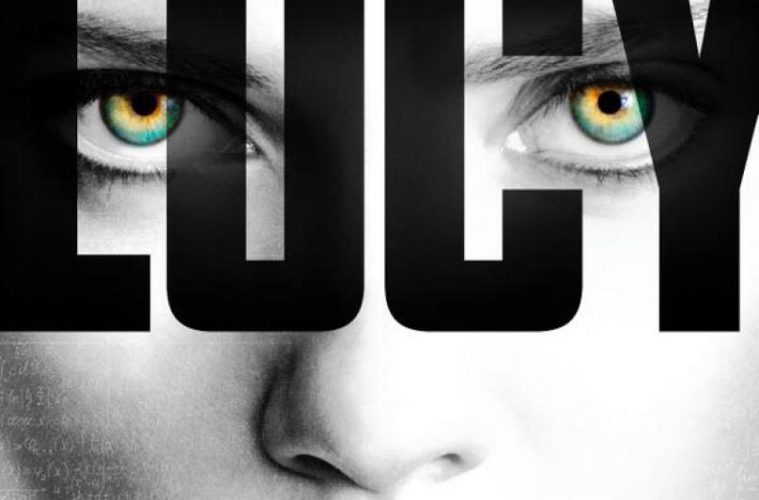

Luc Besson’s Lucy may be the most daft and blissfully idiotic science-fiction movie you see this year. That, of course, shouldn’t prevent you from seeing it, because the truth is that this odd hodge-podge of the cerebral and sensational is one of the summer’s most purely entertaining experiences. There’s not a bit of the ridiculous science that makes any real-world sense, but Scarlett Johannson, playing the titular drug mule who gets a mental upgrade via synthetic CPH4, forms a demented partnership with Besson’s visceral styling to deliver a B-movie delirium the film’s trailers barely hint at. As much fun as breathlessly devouring a dime-store pulp novel on a lazy Sunday afternoon, Lucy is a delightfully eccentric addition to the crazy French director’s filmography.

Things get off to a delightfully weird start when Besson’s camera settles on a primeval watering hole where a female proto-human turns and stares directly at an unassuming audience. This is the first Lucy, a hominid progenitor of the human species, and she’s shortly replaced by Johannson’s Lucy, a distressed expat party girl who runs afoul of Korean mob types led by Jang (Oldboy’s Choi Min-sik). Jang forcefully enlists Lucy in the smuggling of a new illicit party drug by having the merchandise sewed inside her abdomen and sending her on her way back stateside.

When the package ruptures and spews the CPH4 into Lucy’s system, she finds herself “colonizing her own brain” and developing enough super powers to furnish an entire team of X-Men. She’s off across the globe on a mission of revenge, survival, and enlightenment, underscored by an extended science lecture about the capacity of the human intelligence given by Morgan Freeman’s Professor Norman. This overt show-and-tell session, complete with helpfully blunt stock footage (including sections from Samsara), should slow the film to a halt, but the content itself is so absolutely absurd and scientifically wrong that it becomes strangely compelling.

There’s a tension at work in the film, not tied to the ultimate fate of Lucy, but to the prospect that Besson might be able to keep topping himself in the department of imaginative stupidity. It’s a task he rises to the occasion of, and Lucy has that pleasant distinction of being the kind of movie where each fifteen-minute stretch is markedly more insane than the one that followed it. You can roll your eyes at the film’s active embrace of that scientific myth that we only really use 10% of our brains (hogwash) or the conceit that improved brain functions would easily allow Johannson to mentally flip cars and generate velociraptor talons with a mere flick of the wrist. You could do that, but you would be missing most of the fun and, yes, thoughtfulness that Lucy has to offer via its particular brand of pulp sci-fi.

In truth, Lucy is a hyperactive return to form for Luc Besson and his overall best movie since 1997’s similarly over-heated The Fifth Element. The French director has had his hands in plenty of projects since then, but has never achieved the same passionate, heedless intensity that Element generated. Working with a bold kind of graphic novel bluntness, Besson wastes none of his stark-raving premise, and by conjuring increasingly fantastical images he actually redeems the blatant factual idiocies the script commits. For one thing, Lucy resists becoming an action movie in the usual Besson mode, favoring a hallucinogenic escalation of Johannson’s abilities over a series of Superman-style set pieces. Jang and his gangsters never disappear from the story, but they fail to generate tension in the face of Lucy’s God-like ascension.

As the story grows sillier, you can sense Besson himself mocking the elastic reality of most big-budget genre cinema. My favorite touches are the giant place-cards that tick off the drug’s escalation in Lucy’s system, signaling 10%, 20% on to 100, as if the mind were a file being downloaded. In favor of bombastic action to signal the transition of acts, we are treated to shifts in human perception that introduce some big and crazy ideas about where Lucy’s evolution is taking her. This is the movie that Wally Pfister’s listless Transcendence wanted to be; it has the cheerful spirit of golden-age science fiction and some of the curious wonder too. It may exist in a bizarro universe where legitimate scientists spout theories debunked 60 years ago, but it treats its world with a refreshing, wide-eyed fascination.

If the story itself is a flimsy bit of hokum, it does make an acceptable structure upon which to hang some great sequences and a captivating performance by Scarlett Johannson, who now completes a kind of absurd trilogy of characters who find themselves off the map of regular humanity. In fact, Lucy as a character has much more in common with the operating system from Her and the alien predator of Under the Skin than she does with Black Widow. Johannson starts as a nervous jittery accessory, moves to the beautifully deadly model of female power that Besson typically adores, and then heads down a more interesting trajectory that features strong, focused acting in service of some mind-bogglingly over-the-top dialogue. A scene where Lucy places a call to her mom, while being stitched back up in the hospital, is a real corker; Johannson channels odd wells of emotion as she tells her mother she can remember what the breast milk she had as an infant tastes like.

There’s no one working on the film who doesn’t realize how ridiculous the premise is, but Besson keeps the whole thing running on such a giddy vibe that we find ourselves rushing towards the final trajectory and going with it. Along the way, there’s some great filmmaking that reminds of the matter-of-fact brashness of French comic books; when Lucy is caught in the hotel lobby, being manipulated into a trap, the jarring glimpses of stalking cheetahs humorously enhance the scene despite their obviousness. The sequence that follows, with Jang and his henchman interrogating Johannson is terrific in the way it allows a palpable and seeping panic to sink into a surreal situation. The film is full of stand-outs though, including a mutation in an airplane bathroom, a car chase that looks like it was pulled from Inception, and a final vision quest that rewinds and fast-forwards the biological and geological history of the Earth as if it were a VHS tape.

Lucy isn’t a great movie—by some measures it may not even be a good one—but I found it to be a great entertainment and by the rules it sets up for itself, it amiably succeeds. I didn’t believe a word of it but I was oddly stirred by its awareness of human endeavor and adaptation. For a movie with shoot-outs and gangsters and drug mules, it keeps casting quizzical glances towards the cosmos and our own mysterious internal universes. That Besson mixes the mumbo jumbo with a hearty dose of schlock is much appreciated.

Lucy is now playing in wide release.