Don’t Leave Home has an opening composition reminiscent of a postcard and a closing moment like a strange dream. Between these moments is a film that turns idyllic natural beauty into an ominous force, and ventures into nightmare territory before reaching its catharsis. Writer and director Michael Tully prefers an economical narrative language, and Don’t Leave Home is an 86-minute film that lives on the brevity of images. Tully shows these images and then imprints meaning over time; take for example the dioramas which serve as the opening credits before the viewer is introduced to them in a more traditional narrative sense (first positioned in an art gallery, then through dialogue). The viewer is already open to ideas of process via the crisply cut prologue with a painter (shot gorgeously in 4:3), so notions of creating and shrinking things from lifesize scale to canvas is already elemental to the film’s aesthetic. This reliance on pure imagery allows Tully to master his tone, making Don’t Leave Home a wonderfully atmospheric and occasionally abstract poem.

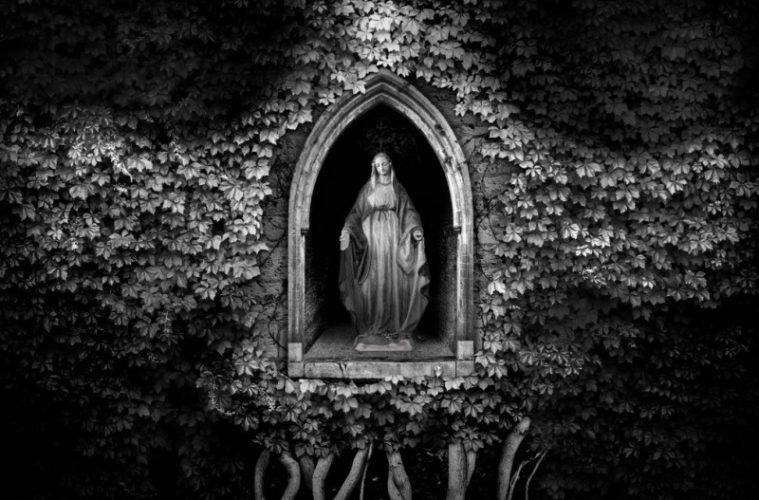

During the aforementioned prologue, we meet Father Alistair Burke, a priest and painter in Ireland who has a particular gift. Years later, American artist Melanie Thomas (Anna Margaret Hollyman) has created dioramas depicting strange incidents which occurred in Ireland, including the one from Burke’s past. With her exhibit about to open under the shadow of a scathing review, Melanie travels to Ireland on the invitation of a woman who lives with Burke in his crumbling rural estate. Once there, Melanie learns that being commissioned for a new diorama will be the last thing to hold her fixations. Soon, Melanie is a fish out of water, troubled in her sleep and gradually uncertain of those around her in her waking hours.

Tully’s shift from 4:3 in the prologue to a widescreen format is effective in how it suggests something ingrained in the psyche and yet of another time, like an old dream you may not be able to piece together in words or images, but is there in its feelings: a tingle down your spine, your ears shifting back, or the buzz in your head that something is off. This purgatory of non-space and half-dreams is where Don’t Leave Home resides, somewhere between the comfort of recent wakefulness and unease as the dreamworld spills off. These tonalities are accentuated in Zach Clark’s editing, which features a series of fascinating dissolves and razor-sharp cuts.

Just as Melanie jokes about early on with regards to walking the grounds, Don’t Leave Home leaves a trail of narrative breadcrumbs, and each piece festers with sinister hints and ominous foreshadowing. It gives the very classic horror movie sense of, ‘oh boy, something is afoot,’ yet with no concrete evidence to support a case, just strange gazes and ambiguous sentences (and a title which begs repeating throughout). These looks and words soon shift into some quite terrifying images, ones that often play with the core conceit of wakefulness and rest, holy and unholy. For as much as Tully is concerned with faith and ungodly acts of God (or someone else), he is equally concerned with the artist, with the process, and with creation. The film meditates on how an artist houses their creations, and about the toll those creations take—on you and those around you, or even those you study. How you take a part of your art, and how it takes a part of you. The things or people studied and used as metaphorical clay enter the artist’s life beyond the page or canvas which they are placed, and exist as both beauty and burden.

Before these heights are reached, Tully focuses on process; he focuses on smeared paint and sculpted clay in brief yet texturally sublime montages, which make for the films most peaceful (and later, most poignant) moments. As mentioned earlier, Tully’s images evolve over time. Rays of sunlight begin as divine and end portentous, and clumps of mud congeal into narrative signifiers. Even if all of the narrative pieces do not fall into place, the remaining gaps leave room for some of Tully’s most interesting ideas.

For where Don’t Leave Home perhaps intrigues most is in its more abstract elements. A fleeting image comes to mind, where the motif of a cloaked figure is momentarily reflected in the shifting shadows on Melanie’s face as light rapidly changes. This moment is so minute, it could be argued not to be intentional, yet its effect is nevertheless chilling. Further into abstraction, the climax largely foregoes dialogue as it veers toward dream logic, causing motifs to weave into each other as Tully builds toward the final payoff.

Don’t Leave Home transposes us to the purgatory between consciousness and slumber, at a time when it is uncertain which is preferable. The allure rests in the gradual unfurling of its narrative, luring us to a place of uneasy rest, yet rest all the time. There, in repose, it has you.

Don’t Leave Home is now in limited release and on VOD.