Between 1979 and 2015, the Chinese Communist Party was engaged in one of the greatest attempts at totalitarian social engineering in human history: the national one-child policy. Intended to stymie overpopulation and combat famine, the policy mandated that Chinese families (with few exceptions) must have exactly one child, or else face state-sanctioned punishment ranging from public ostracism to property seizure to forced abortion and sterilization.

Chinese-American expat Nanfu Wang and Lynn Zhang’s sobering new documentary, simply titled One Child Nation, largely eschews the kind of abstract, “objective” historical and political analysis one would expect to find in, say, a CNN production. (Amazon Studios, the film’s distributor, is evidently unconcerned with provoking the ire of state-backed Chinese investors.) No “expert” talking heads rattle off statistics or theories or digestible factoids, and in fact the particular “how”s and “why”s of the one-child policy’s design and implementation are only broadly outlined through archival news clips and Wang’s expository narration. Instead, leveraging her proximity to the subject in ways few Western-born filmmakers could easily replicate, Wang–herself a product of the first one-child generation–places personal narrative front and center, starting with a visit to her rural hometown and spiraling out to produce a deeply personal snapshot of social engineering through the eyes of those predominantly working-class people most affected by it.

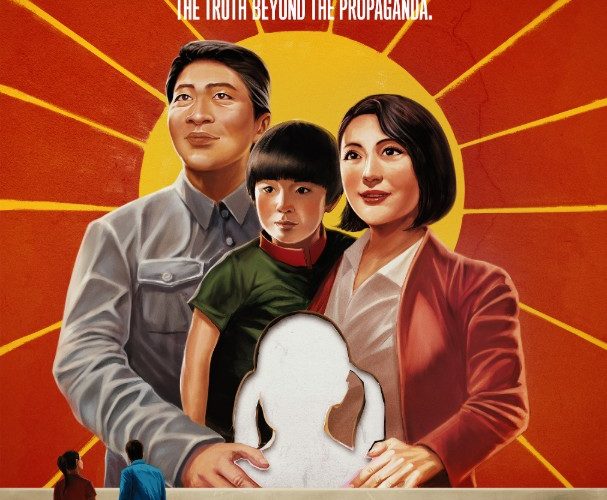

Wang begins with herself, recalling a youth spent immersed in omnipresent CCP propaganda, from which photographs and video clips are interspersed throughout the film. Nathan Halpern and Chris Ruggiero’s score rather needlessly attempts to underline the Orwellian spookiness of these images, as if they didn’t speak quite loudly for themselves: in one clip from a national TV broadcast, a young boy in traditional folk garb sings cheerfully of the punishments awaiting any families foolish enough to defy the wisdom of the Party. It’s a level of absolute, multifaceted media compliance which Donald Trump only dreams of, pitched at a level of mawkish sledgehammer bluntness only possible in a nation where state propaganda exists in an uncontested cultural landscape. Lest we doubt the efficacy of this iron-fisted approach, Wang’s own family–residents of a farming village far removed from China’s urban centers of partisan power–chime in with eerie, almost word-for-word recitations of the party line on family planning.

From here the film spans out to an ever-expanding network of individuals in myriad locations whose lives were shaped and dictated in some way by the titular policy. Local authorities and government-employed doctors recall their complicity in a web of systemic violence that disproportionately targeted women: pregnant mothers drugged and aborted at gunpoint, infant daughters left for dead by families in need of male heirs, midwives compelled to commit infanticide or else lose their profession. (The devastating intersection of state-dictated morality and culturally engrained misogyny may strike a cord for citizens of Alabama, an ironic parallel not lost on Wang.) Many echo the all-too-familiar refrain of “just following orders,” but a few figures stand out for their conscience: a former midwife, tortured by guilt, who became a fertility specialist to “repent for the lives [she] took”; an artist whose macabre work preserves discarded human fetuses recovered from landfills; a sibling team of convicted human traffickers, publicly condemned for rescuing infants left to die in the streets and selling them to orphanages for a meager profit.

In the more documentary-standard final stretch of the film, Wang also touches briefly on the fate of Chinese infants adopted overseas, bringing in an American couple who specialize in reconnections adoptees with their birth families–or at least attempting it. It’s slightly discordant with the intentionally localized scope of the film’s first two-thirds, which take after Shoah in recreating historical nightmares through only the haunted voices and faces of those who bore witness, and the spaces in which they did so. This expanded section does, at least, follow through on chasing the incalculable personal fallout of one absolute policy in the most populous nation on earth. What it lacks in formal finesse or educational scope, the film more than compensates as a taut illustration of the profound disconnect between high-level social engineering and the lived social realities that totalitarian policies entail. It’s quiet, feminist rage against Big Brother.

One Child Nation opens on Friday, August 9.