In supposing that there’s entertainment to be found watching torture onscreen, a horror/thriller subgenre was created that emphasized it to “pornographic” heights and thus separated itself from the well-worn slasher title through how excessively the body would withstand the most gruesome of gore. Yet for every occasionally risky or at least admirably grotesque example of these films, there are just as many risible cases in which their excess is under the guise of being meaningful; as a post-9/11 cinema has produced dozens upon dozens of glib, opportunistic reactions to a confused world with filmmakers half-heartedly equating their faux-gritty grand guignol to media-spread images of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay.

And the problem that comes with Big Bad Wolves is that its excessive violence is too intrinsically tied to questions of morality to simply create excuses of “it’s just entertainment.” But in the film’s gleeful race to get its three primary characters into a dingy torture dungeon (a cross-cutting montage of the trio near the end of the first act announcing to the audience to prepare for the main event; to which it’ll never create enough moral distance from), it unintentionally eradicates any chance of enjoyment.

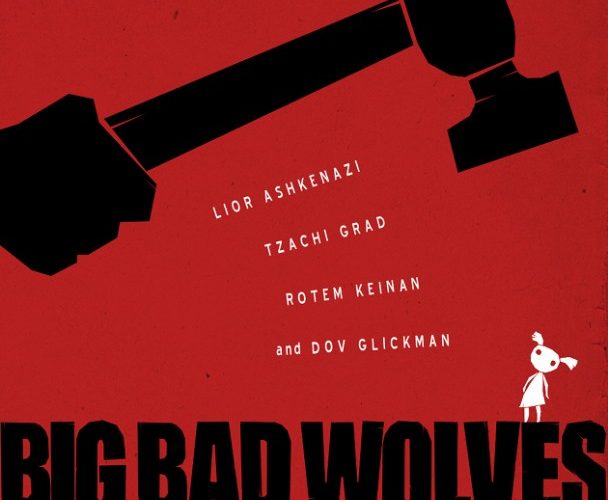

Our three being the obviously leather jacket adorned rogue cop Miki (Lior Ashkenazi), the nebbish teacher Dror (Rotem Keinan) and bourgeois Gidi (Tzahi Grad). After the body of Gidi’s young daughter is found (and obviously in line with the film’s miserabilism with marks of sexual abuse), Miki suspects Dror, which swiftly results in a brutal beating by him and his two other police goons. Though, unfortunately for them, it’s caught on a child’s iPhone and subsequently uploaded online, which embarrasses the police force and thus frees Dror. Yet Miki and Gidi won’t have any of it, capturing Dror and subjecting him to their own brand of justice.

It would appear that it wants to say something about the law, particularly in regards to Israeli society, yet it’s unfortunately too eager in getting to the torture, the allusion to actual politics revealing itself as simply first-act time-filler. The extent of its commentary is just stating there’s often a misconceived righteousness that leads to operating outside the law, which seeks more to reflect film tropes than actual real life.

And therefore, a moralising born out of movies, rather than real consequences, leads to violence of the same effect; breaking a finger is only breaking a finger. Because of the close-ups on the carnage, it becomes less about the action of the character than the effect on the audience. It’s essentially no better than the characters it’s criticizing.

And eventually it becomes more and more problematic through the joy it takes in its violence; the introduction of a blowtorch, for example, serving not as a further descent into madness, but rather the filmmaker’s latest trick for destroying the human body. It’s as if there’s worry about the audience getting bored just by broken bones, cuts and repeated threats to masculinity with swift kicks and pointed guns towards the crotch — itself a reminder of the film’s self-awareness at the largely male audience that’ll cheer it on through the genre festival circuit.

But mutilation doesn’t make up the entirety of its runtime. As to only add to its offenses, it’s the kind of film in which the ripping of someone’s toenail is interrupted by a pop-song ringtone. Beyond just being a ridiculously tired and unfunny joke, it speaks to the film still counting on the banality of evil; the process of crime contrasted with everyman tasks, which at this point is just banality itself, having been driven into the ground by post-Tarantino crime films. And coupled with a montage of baking a cake set to Buddy Holly’s “Everyday” (sorry, Lynne Ramsay already made eyes roll with that one), raises the question of if we’re supposed to be horrified by the violence, then why is it being smothered in comic-relief? Rather than create levity, it instead accentuates its overall lack of responsibility; a seeming non-committal to the weight of its images.

And with one last slap against the face of the audience, it ends with a portentous twist that makes the message amount to nothing more than “everyone is horrible.” This twist seemingly wants you to reconsider everything you saw before and if the violence was justified, but it only makes its repugnant manipulation more apparent. Even though it seemed to want to deal in ambiguities the entire time, not revealing if Dror was guilty or not, that’s still not excusable for the position it puts the audience in, and more or less the entire point of watching the film. The next time you want your exploitation film to actually deliver on its transgressive nature, don’t invoke things you have no interest in actually addressing.