So much of what we do in our lives comes down to a matter of could versus should. Many of us want to prove ourselves worthy by doing something nobody has ever done before, yet the hubris of such a desire often leaves us paying a price we neglected to realize had to be paid. Even if “should” factored in, however, the end result still wouldn’t be guaranteed because good intentions aren’t enough to offset that cost. Just because the pain and suffering we experience due to the untimely death of loved ones isn’t fair doesn’t mean bringing them back to life suddenly wipes the slate clean. There are psychological and emotional ramifications to consider for all parties involved. Making life ultimately ensures the taking of it too.

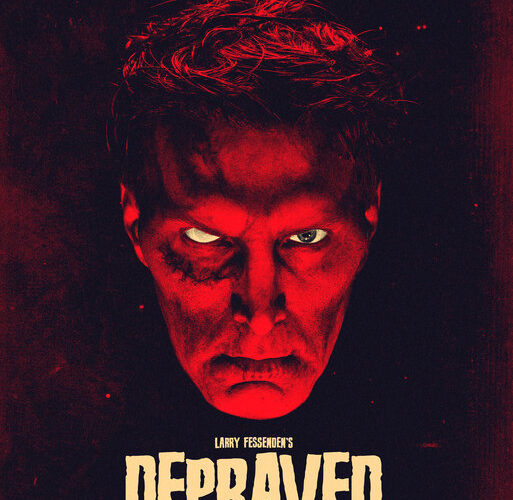

It’s in this mode of reconciliation that Larry Fessenden reworks Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein by providing not one but two doctors hovering over their cobbled together experiment of blood and guts. One (Joshua Leonard’s Polidori) wants to play God and commodify the act in order to turn a profit. The other (David Call’s Henry) wants to correct the flaw in God’s plan by saving those who never deserved to die. The opportunist and idealist make a pact wherein each of their goals could come to fruition if their illegal test run delivers the data to support continued financial assistance. Henry solves the puzzle of creating a suitable subject while Polidori supplies the drugs to keep its rotting flesh alive. Is one better than the other or are both Depraved?

There’s a line that must be crossed and as a result the whole is more about whether they acknowledge the wrong they’ve committed in the aftermath. It’s not just the wrong of messing with the science to create a man and assume he understands complex subjects that children have years to comprehend. The even bigger issue at-hand is the fact that they required a brain to give Adam (Alex Breaux) everything he needs to survive. As such, there’s a person (Owen Campbell’s Alex) trapped inside as memory, nightmare, impulse, and sadness. Henry truly does want Adam to succeed and knows healing the brain within his skull is a huge piece towards achieving that goal. But as those synapses reroute themselves, more of Alex begins rising to the surface.

This is the film’s best aspect because it deals with past and present as echoes reverberating back and forth. The life Alex had with Lucy (Chloë Levine) manifests as a hole in Adam’s heart that he didn’t realize existed until after meeting Henry’s ex-girlfriend Liz (Ana Kaye) and Polidori’s rich pharmaceutical company heiress wife Georgina (Maria Dizzia). Those two broken relationships don’t necessarily provide him examples of love, but the couplings themselves spark feelings his brain used to have and thus puts him on a one-track path towards finding “a girl” of his own. Because this is Frankenstein, that journey cannot end well no matter his own good intentions. These are all men acting on selfish desires without the capacity to empathize with the targets of their affection.

What doesn’t work as well is the fatherhood commentary. From Alex’s visceral rejection of the concept to Henry’s skewed perspective merging parent with warden to Polidori’s “cool” uncle causing trouble before dropping Adam back off with dad, it’s too overt to ever really say much beyond paternal instincts being purely about gain rather than support. To his credit, Henry does gradually become aware of this flaw and attempts to correct himself despite it already being too late. His realization is in regards to his pursuit for something down the road blinding him to the problems he must confront right now. He’s not lying when he tells Adam that he didn’t chose his name for its Biblical connotations. Henry’s backstory is much too heartbreaking for such simplicity.

This was a big surprise for me considering I entered Depraved with a mindset that wasn’t quite prepared for how quiet and introspective it proves. There’s a through-line concerning PTSD and Henry having fought in the Middle East with Liz being a therapist and thus a proponent for him to receive the help he needs before his chose to dive into his work and exorcise demons on his own terms. This character is therefore simultaneously victim and perpetrator, escaping trauma by creating trauma in another as though they won’t feel as helpless as he does in the process. That’s basically what Adam is in some respects. He’s a walking, talking personification of PTSD with wildly violent mood swings, pervasive melancholy, and a wealth of belated contrition.

Adam is literally a shell composed of the shadows of other men haunted by their own uncertainties, tragedies, and identity crises. Henry wants to tap into those voices without thinking (and in some cases without knowing) about how fresh those internal wounds are. Polidori conversely wishes to spark a reaction by drowning Adam with stimuli to study his limitations and push him to the edge of them. They are both in turn using their creation as a sounding board to get what they want for themselves. The former is damaged and searching for a cure while the latter is a sociopath desperate for an outlet to enjoy his hedonism and experience the joy of watching the pain he wrought. And Adam follows in both their footsteps.

That he possesses the self-awareness to realize his own descent towards mankind’s depravity is as inspiring for our ability to improve as heartbreaking in our readiness to devolve and become our worst selves via social conditioning. In this respect the fatherhood idea finally arrives with implicit intent. Children can only know what they’re taught—good or bad. So Adam succumbing to baser desires was foretold considering the men who raised him were driven by their own too. Rather than the world being unready to accept him for what he is, though, it’s Adam himself who cannot. Talk about a common trait many cope with on a daily basis. Victims to our own insecurities and fears, we too often project them onto others instead of confronting them head-on.

Depraved is now in limited release.