It’s not every day we see a remake of a currently running franchise, but now there is Child’s Play. While original screenwriter Don Mancini continues to advance the escapades of his version’s murderous doll possessed by a serial killer’s soul (most recently in 2017’s Cult of Chucky with a SyFy television show arriving in 2020), MGM and United Artists decided to flex their legal retention of ownership by branching off anew. After Mancini unsurprisingly declined to provide them his seal of approval—brand confusion is definitely not something he’d willingly condone—the project moved forward under the stewardship of writer Tyler Burton Smith and director Lars Klevberg. Thankfully, they knew to make it their own.

Whether a result of needing to stick solely to what was kept in the divorce or an actual desire to cut a fresh path, the only similarity between Mancini’s horror and Klevberg’s reboot is the generic premise wherein a sentient plastic doll kills humans. The world has changed these past three decades–thus a toy coming to life skews more towards science fiction than Charles Lee Ray’s supernatural voodoo fantasy. With the fictional specter of Skynet looming and the reality that Alexa smart home devices have infiltrated civilization, mankind’s hubris is already primed for self-destructive imprisonment and potential annihilation. Once you give a machine the keys to your convenience, its unyielding objectivity will inevitability conflict with your safety and that of your loved ones.

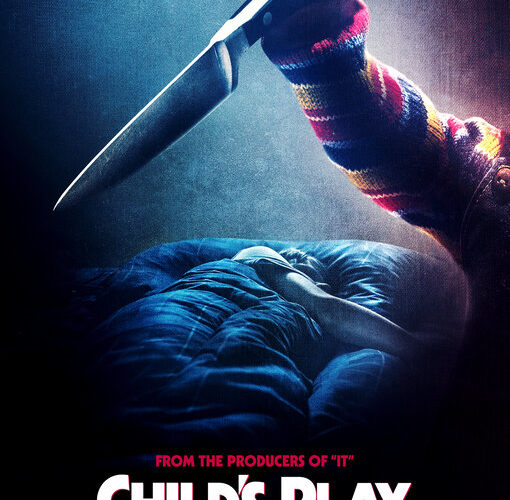

On paper this sense of omnipotent power is much scarier than a two-foot-tall, knife-wielding plaything you could punt across the room. That’s why Mancini has turned his films into cult comedies rather than the more straightforward fear machine Klevberg hopes his remake proves. The possibilities become endless when one malicious doll can act as a computer virus infecting every product with its same built-in Kaslan infrastructure. Whereas that technology’s namesake (Tim Matheson’s Henry Kaslon) strives to connect people (and surely profit off the sale of their analytical and searching trends), an autonomous force within its code could expand its reach and enforce a totalitarian strength globally. Maybe that’s a direction the filmmakers will go in the future. For now, though, their sights are set on the Barclays.

Karen (Aubrey Plaza) just moved her son Andy (Gabriel Bateman) to a new apartment to restart their lives. Their boxes are still packed and she can’t help seeing how much of a struggle it’s all been for him. Rather than try to meet new friends, Andy spends his time on his phone to revel in the memes surrounding the bane of mom’s 9-to-5 retail existence: Buddi. This tech-integrating toy is almost obsolete with an upgraded line (Buddi 2) yet to be revealed, so Karen knows she can twist her boss’s arm into letting her take a defective return home for free as a birthday gift. Andy is definitely too old for it, but she knows he’s the perfect age to still enjoy what it has to offer ironically.

What’s interesting about the genesis of this Chucky (voiced by Mark Hamill, replacing Brad Dourif) is that its bloodlust isn’t automatic. A disgruntled employee at Kaslon’s Vietnam factory might turn off this single unit’s security protocols and safety features, but he doesn’t teach it to be cruel. That happens courtesy adolescence’s nihilistic apathy. It hears Andy swear and repeats him because its profanity filter is turned off. It experiences the pleasure he and his friends (Beatrice Kitsos and Ty Consiglio) show while watching slasher films on television. And it listens to Andy’s hyperbolic declarations of hatred towards shady figures like mom’s boyfriend (David Lewis). Violence seemingly becomes Chucky’s most direct road towards young Andy’s heart.

Think of it like a variation on “The Monkey’s Paw” wherein a person’s three wishes are granted with dire consequences. Rather than adding collateral damage to each command, Chucky acts on everyone’s words to their last dispassionate letter without caring about intent. If Karen flippantly says the cat is the reason Chucky is locked away from playing with Andy, the cat obviously has to go before reclaiming his freedom. He thinks in black-and-white, remembering literally everything thanks to audio- and visual-recording capabilities–more than the means to commit homicide, this killer has the evidence that would prove a human had motive enough to be blamed by the authorities. Yet the script doesn’t capitalize on this to create any grey areas.

Because Andy is older than his 1988 counterpart, he has the wherewithal not to blurt out that his toy is alive. So instead of a murder bringing Detective Mike (Brian Tyree Henry) to the Barclays’ apartment, he’s merely an acquaintance because his mother (Carlease Burke’s Doreen) lives down the hall. The first death is thus swept under the rug with Falyn and Pugg acting as confidantes. The second forces Mike into Andy life in a professional capacity, but there isn’t an inclination that the boy is at fault. Smith tries to inject a line of dialogue implying Chucky might be the scapegoat of a delusional psychopath, but the film has already proven this isn’t true by showing–beyond a shadow of a doubt–that the doll did it.

Chucky’s abilities to frame people are therefore used as threats to keep Andy in line. This is a missed opportunity: it ensures the plot will never possess ambiguity or intrigue besides whether or not the robot will be stopped. Child’s Play becomes a matter-of-fact A-to-B progression devoid of wiggle room where obstacles manifest as physical impediments to survival instead of narrative blockades to our understanding of what’s happening. While this renders the whole less robust in story-telling prowess, it also augments the action of a no-holds-barred climax that sees Chucky using his powers to their fullest possible extent in an environment that guarantees his advantage. The real fun arrives with hardened teens showing their mettle as adults run and scream.

The film thus proves a mixed bag–heavy exposition marked by brief moments of carnage before Chucky is allowed to wreak havoc with impunity and dial things up to where I would have liked him to start. How the toy evolves is authentic insofar as its artificial intelligence learning without a capacity for morality and its character design is sufficiently creepy without needing to try. (Just wait until you see one of the Buddi 2 upgrade skins.) Plaza is good, if under-utilized, while Bateman proves more than capable of carrying the film’s weight on his shoulders as its lead. Henry delivers a wide-ranging performance that elevates the material whenever he’s onscreen and Kitsos steals many scenes with a formidable presence perfectly contrasting her diminutive frame.

Child’s Play is now in wide release.