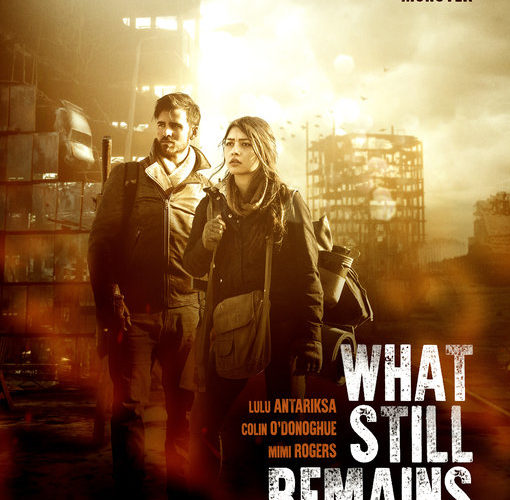

There are two kinds of people still watching The Walking Dead: those who love the gore quotient and believe zombies are the true enemy of the people and those who understand that the undead are merely a catalyst to expose the evil that has always lived within. I’m of the latter group because the drama is always more real when it builds between two very different people trying to survive via diametrically opposed ways than when it’s just the living bashing the skulls of unfeeling hollow shells. So it intrigued me when hearing zombie film What Still Remains called an apocalyptic thriller. The two descriptions are hardly mutually exclusive, but they do both sell vastly different content. Writer/director Josh Mendoza’s world isn’t being consumed. It already has been.

By fast-forwarding through the initial carnage and fallout of what civilization’s destruction wrought, Mendoza is able to create a fresh environment of extremes. He moves twenty-five years away from the viral outbreak that transformed loved ones into “the changed” so that the majority of those left can no longer be defined by the past. Rather than hold onto a sense of what “normalcy” had been, this desolate wasteland is normalcy. Trust in others has now become the exception instead of the rule because anyone other than family poses a risk as dangerously fatal as the creatures they once feared would kill them all. The zombies have therefore become as much a fairy tale as stories of salvation by the ocean. Monsters do still exist, but they aren’t undead.

While we can understand this thanks to a cultural wealth of artistic context, however, Anna (Lulu Antariksa) is quiet literally on her own. She was born six years after the “change” began and thus knows nothing but an isolated life within a cabin in the woods. We don’t know if she’s ever truly seen a zombie since the only people she’s ever met other than her parents and brother (Roshon Fegan’s David) have been traders passing through with as much potential for trouble as altruism — each combated by a locked gate and loaded gun. So when the day arrives that leaves her as the last of her people, her choices are simple: the comfort of the only four walls she’s ever known or the unpredictability of everything beyond.

Meeting a stranger days after her mother’s passing therefore brings as much excitement as dread. Peter (Colin O’Donoghue) seems kind enough, but that doesn’t guarantee kindness. So Anna protects herself. She listens to what he has to sell (a community a few days away that offers companionship and protection) at arm’s length, weighing the cost of supplying him with her trust. And if she had anyone else left to give her a reason to stay, she probably would have. But a life without backup in this world wouldn’t be sustainable for long. While Peter’s group may not prove exactly what she wants, they may be what she needs — if only for a little while. He describes them as God-fearing like her mother and thus an opportunity worth taking.

While we might never see a zombie onscreen, we do eventually catch glimpses of pure evil. What Peter teaches Anna first is that there are now men dressed as “the changed” who wander the trees in search for victims of their own. He calls them Berserkers and from what we see the name appears highly appropriate. They must therefore pray to be spared by the virus that’s taken so much and be smart enough to avoid those warped minds threatening to take some more. Unfortunately for Anna, leaving her property places her in the crosshairs. To travel to Peter’s home is to hide from anything that may cross their path. And just as she finds herself believing his tale of sanctuary, she remembers how nothing is free.

Saying much more would ruin Mendoza’s intentional mirroring of two sects of people (Peter’s group led by himself, Jeff Kober’s Zack, Mimi Rogers’ Judith, and Dohn Norwood’s Ben versus the Berserkers as portrayed by a captive in Peter O’Brien) that fluidly moves between good and bad until the delineation all but disappears. His film’s title is a literal one because it shows how two things survive these types of cataclysmic events: hope and greed. Where Anna serves as an example of the former thanks to a mother who ensured she was protected from learning ways in which the sins of man could be warped into necessity, everyone else represents the latter. And much like it is today, religion is revealed to be at the core of mankind’s treachery.

What Still Remains therefore moves beyond social commentary into the realm of entitlement by divinity. It exposes how easily we turn tragedy into a “gift” — how we condone genocide as “cleansings” wherein God chooses who’s worthy enough to prevail. The inherent problem of faith has always been its corruptibility and its promise of forgiveness. As soon as we learn the latter is only a plea away, the former sheds its consequences. And this is only magnified in a lawless land of leaders chosen from those most devout to a scripture of his/her own creation. These opportunists may begin with good intentions, but it’s not long before they’re feeding on the minds of the living as rabidly as the infected. Life becomes compromised as morality’s line fades further towards nothing.

It’s this concept at the back of everything that makes Mendoza’s micro-budgeted production worth your time. Those hoping for zombies stumbling through the forest will be disappointed, but those searching for the complexities of how such things alter our psychology will not. There aren’t many surprises (Peter’s arrival is serendipitous for a reason, his refusal to clarify statements with anything but vagueness an intentional decision so that Anna remains forever vigilant) because the way this situation plays out isn’t surprising anymore. This is what we do: seize power and fight to never let it go. Only those miraculously untouched by this truth can see with open eyes and push back. But as the climax proves, victory will eventually cease to exist. Sometimes the world can no longer be saved.

What Still Remains opens in limited release Friday, August 10 and hits VOD in the US on August 14.