I have to believe Tyler Perry is smarter than this. The primary disconnect between critics and audiences of his films is essentially Roger Ebert’s law, his first rule of film criticism: “A film is not what it its about, but how it’s about.” Perry has in the past churned out two theatrical features a year, with two additional films on the schedule for 2012. Despite a large disconnect, one could refer to him as the “Robert Altman of our generation”, as in that director’s heyday he also cranked out two features a year.

Where the quality disconnects is not so much content as it is in execution; on the stage, subtly gets lost. A general principal of screenwriters (or any writing for that matter) is economy – is there a look or an action that can describe what would take 5 sentences of dialogue? Perry has progressed very little in the use of these devices and is a master manipulator, for when it works, I’m in awe (as it did in Why Did I Get Married Too?). But Tyler Perry’s Good Deeds is a strange journey, also with an uplifting if not implausible ending, perhaps even offensive in a more feminist context.

Where Perry fails in his subtly, he hits us over the head with it and continues to, making sure the audience doesn’t miss any small gesture. He repeats it again – there is no mystery to any character, to the point that the film’s very last scene contains the line “A lot of times in relationships people don’t say what they really mean.” Really? Not in Tyler Perry’s Good Deeds, as the dialogue is the very definition of on the nose.

Perry, uncomfortable out of drag, is Wesley Deeds, a businessman running Deeds Industries, a software company that in recent years deals more in mergers and acquisitions, Bain Capital-style. He’s asked by a member of his cleaning staff and the film’s leading lady, Lindsey (Thandie Newton) if he knows the price of milk. Unlike Margret Thatcher, Mr. Deeds has to look it up and get back to her. Wesley lives in an upscale high-rise apartment with his fiancée, Natalie (Gabrielle Union) who has memorized his routine from putting on his tie, to complaining about the cleaning women, and finally his breakfast (egg whites and oatmeal). Even actresses of the caliber of Newton and Union can’t save the very spot-on nature of the film (really – do we need Natalie narrating Wesley’s morning rituals, isn’t there a more interesting and subtle way to achieve exposition?).

Over a slow-motion shower sequence straight out of a Lifetime Original Movie, we learn in voice-over he’s a member of the lucky sperm club to take over his father’s business – a dream that was never his. Shifting the setting from Perry’s frequent base of operation, the ATL, he’s now in San Francisco in a film that evokes – at least in its screenplay – another fine San Francisco melodrama, Tommy Wiseau’s The Room, one equally as gramatically challenged.

Wesley’s day starts by picking up his brother, Walter (Brian White) the drunken black sheep of the family. Multiple DUIs on his record, he has no respect for women in moments again far too broad for the screen. They’re all kept in check by the matriarch of the Deeds family, pulling the strings like Lucille Bluth is their mother Willimena (played by Phylicia Rashad, again in another stellar performance). When Wesley and Walter are held by a single mother who parks in their space, leaving her daughter Ariel (Jordenn Thompson) in the car, he gets involved in their lives. Admiring the way this women – who works both the day and night shifts after the IRS garners her wages down to $120 – talks to him, he’s drawn in and starts what is the least charming and blandest romances I’ve seen on screen in years.

This film will be successful because of what it is about. Perry is a master manipulator, he knows how to make us feel, even bashing us over the head with “Time After Time” – a trope so common it should be outlawed as too easy. While the performances from the women of Good Deeds are stellar, the direction is lackluster – this is far too easy, and its no wonder Perry continues to churn them out at a rate of potentially 3 in 2012, making up for only one theatrical feature (Madea’s Big Happy Family) and two videos he released in 2010.

Still, Perry is filling a void – Douglas Sirk he is not, an auteur and perhaps movie mogul he is, building both a brand and a physical studio in Atlanta. He is an important filmmaker, I just wish he were a better one. Chronicling and calling attention to the diversity of the black American experience is important and Perry has made many films about multiple income and education levels. He’s less a a satirist, rather an observer of issues whose commentary tells us what we should already know. Clarity and entertainment are important but let’s just call continued, extreme over-simplification what it is: an insult to our intelligence.

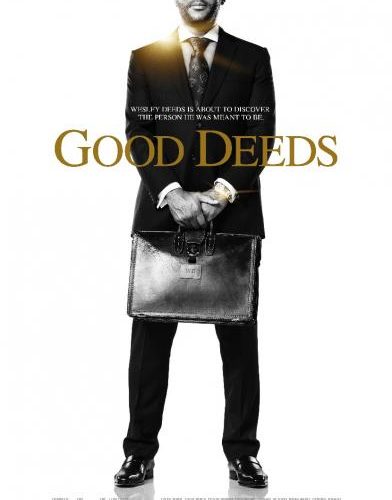

Tyler Perry’s Good Deeds is now in wide release.