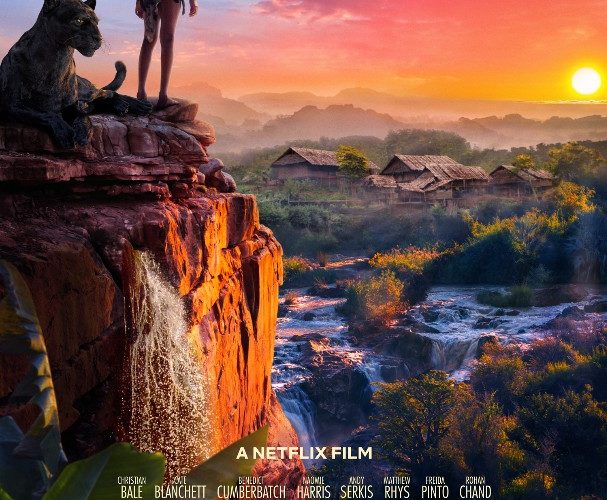

Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle is a strange beast. It’s a dark re-imagining of the world from The Jungle Book, familiar to anyone that saw Jon Favreau’s 2016 reboot to the Disney classic of the same name. Helmed by Andy Serkis (shot before his debut Breathe, but released after), this take on the man-boy Mowgli and his pack of jungle pals strides in technically bold new directions while also wading through narratively thin waters. The result is a film brimming with visual marvel that at first blends seamlessly with its ideas, then begins to unravel once we’re left with the scraps of its story.

Mowgli (Rohan Chand) is not like other boys. Raised by wolves, he communicates with all life in the jungle (except the monkey people, more on them later) and runs on all fours. This means he is a part of the jungle community, its customs, and its political machinations. Mowgli the film sets up a world around Mowgli the boy where animals hold meetings to make decisions and if a leader misses a kill whilst hunting, he must fend off an ambitious member of his own pack. As Mowgli prepares for The Running, an event for young cubs to see if they’re fit to be part of the pack, larger forces of nature and man conspire around him. Soon, Mowgli must face what it means to be a human being, and question if he has a place amidst beasts.

The first reel of Mowgli is sort of stunning. It’s all melodrama and big ideas around life and death, man and animal. Take the shot of an animal’s eye as it takes its last breath (a running theme here being honoring those you kill), which fades into a pristine shot of vines and trees to make for an exquisite meditation on the natural cycle of life. With a single dissolve, Serkis serves up refreshingly concise ideological and thematic wonders.

The prologue dishes out a Lord of the Rings-esque tableaux, complete with Cate Blanchett narration and a slaughter of man by animals fit for a Grimm fairytale. Soon after, council meetings are held by wolves on a dark, jagged cliff and a sadistic tiger (Benedict Cumberbatch) makes mentions of tasting blood and doing bad deeds. It’s almost impressively seedy, and yet is packed with such silly dialogue delivered by mega-stars in gorgeous motion capture that it is oddly jaw-dropping in a very uncanny valley, tingle-on-the-back-of-your neck kind of way. Here, in these early moments, one can perhaps become most enthralled in Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle; when sweeping emotionality and darkly rich promises of bloodshed are yet unfilled, but teased as forthcoming.

All of these elements are a showcase for, and in turn, showcased by one element: motion-capture. It’s hard to avoid when one becomes cognizant of Serkis’ extreme passion and aggressive experimentation with the technology. He is a frontiersman, coaxing richer textures and deeper, subtler expressions with each foray into the digital unknown. It’s heart-pounding to see once one starts to consider it, which is an interior digression that is impossible to avoid once you stare into the absolutely manic tiger eyes of Benedict Cumberbatch.

Serkis captures his often immaculate motion-capture with a digital cinema style that evokes Peter Jackson and James Cameron. These gestures work in sweeping movements, but sometimes fail Serkis in small ones. Just as the familiar narrative of Mowgli is held up against the edges of digital experimentation, so too Serkis’ cinematic grammar meshes the old and new. He openly tests his performance-capturing technology against visual techniques that are now tried and true by digital auteurs before him.

The second half of Mowgil takes an abrupt shift that at first feels fresh, but soon becomes stale. Hints of Apocalypse Now become Apocalypse Later as the narrative engine chugs, and even further unions of theme and visualization (this time around real versus motion-captured animals, as well as the earlier man / beast intersection) cannot save Mowgli or Mowgli from losing their beastly edge. As the film staggers into its third act, moments that should be loaded with significance are brushed over (see: reunions) and thematic conceits are foregone or needlessly repeated in the name of narrative conclusions. Serkis builds multiple forces of evil but somehow under-uses them, nor does he capitalize on the momentum he has built in the first half.

Rousing sequences occasionally shine through, including a banger but all-too-short segment in the monkey people’s lair or the visualized similarities and differences of man and animal shown in The Running; or the light meditative touches Serkis sprinkles in. Unfortunately, the affect of these elements become deadened by the film’s halfhearted conclusions on its ideas. Oh, did I mention Christian Bale is in this movie? There’s a lot going on, and yet somehow not enough.

Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle hits Netflix on December 7.