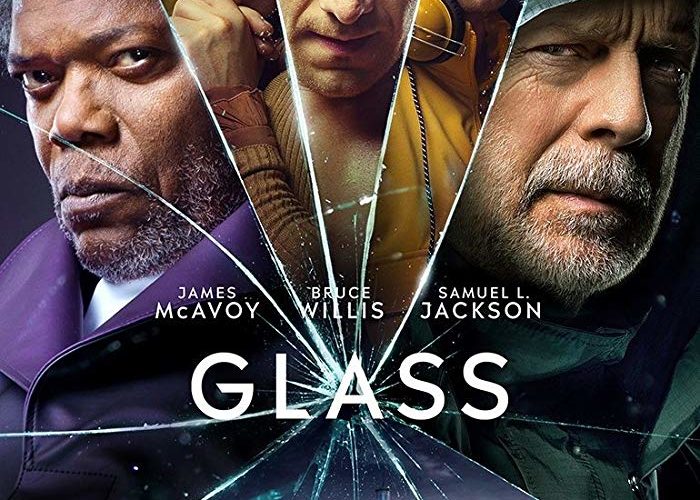

Almost three years ago, M. Night Shyamalan—famous and infamous for his twist endings—pulled the greatest cinematic reveal yet in his career. At the end of Split, the story of three girls kidnapped by a man with Dissociative Identity Disorder, it is unveiled that not only is that man capable of supernatural feats, but that the whole movie had been a sort of stealth sequel to Unbreakable, his 2000 film starring Bruce Willis as a man realizing he may be a superhero. Now, with his narrative cards laid firmly on the table, Shyamalan returns with Glass, the presumptive finale to his comic book movie trilogy, a film that seems designed to disappoint, delight, and confuse in equal measures.

Coming out of Split, it seemed as though the pitch for a sequel would be rather easy to guess; David Dunn (Willis) has to track down and stop The Beast (James McAvoy) from causing more harm. However, Glass uses this idea as a mere jumping-off point to the real story, wherein Dunn and The Beast are both captured by Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson) and brought to a mental hospital for evaluation and possibly treatment for their “delusion.” This hospital also houses Unbreakable‘s Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), also know as Mr. Glass, who may or may not have a few nefarious ideas on what to do now that two super individuals are under his own roof.

The concept of making both superheroes and super villains having to confront their possible mental and emotional damage through forced therapy stemming from their actions in the real world is an interesting one, though perhaps a little underserved here. Dr. Staple is lent a level of empathetic earnestness by Paulson’s expressive eyes and comforting voice, which goes a long way toward making her interest in this particular trio seem genuine and earned. However, having gone through two movies wherein we see David and The Beast at their best, it is a narrative bridge too far to expect that the audience will ever doubt that these men are who they claim to be. Luckily, both Willis and McAvoy dig deep to show their characters truly struggling with the possibility that they may just be two damaged men with slightly more strength than the average person.

Jackson is the real star of the show, as well as the true protagonist, though he is deployed with stealth and cunning to match his character. If this film is, at its core, a fight for the souls of the presumptive hero and villain at its center, then Elijah is the Angel on the shoulder opposite Dr. Staple’s Devil. Perhaps those two should be swapped, considering that Elijah’s adherence to comic book lore necessitates that his plans always involve imperiling innocence. Though, given that the audience is spoiling for a fight, that means he’s really working for our benefit. Jackson relished his chance to take the peculiar, obsessive Mr. Glass for a spin again, and his pleasure at his deviousness is the bright spot in what is at first a rather dour and stoic film.

That Shyamalan formalism and earnestness (which could also be termed as gravity) does hamper the film’s pacing a little bit. This is a movie about broken people, and there are close-ups and memories and static shots galore to make sure we can feel that emotional weight. A scene in which all three super-people are aligned to speak with Dr. Staple overstays its welcome, though the effort does mine some compelling character dynamics for the latter half of the movie. All the same, there are only so many times we need to see Joseph Dunn (Spencer Treat Clark), Casey (Anya Taylor-Joy), and Mrs. Price (Charlayne Woodard) talk about comics or their tropes and then explain those tropes to one another or to disbelieving third parties. While I would argue that these moments serve to gird the film’s central conceit with regards to how comic books amplify inherent knowledge in the world of the movie, the essential clumsiness of these scenes cannot be ignored. Odds are that when detractors decide to begin picking at this movie, these will be the first scraps they sink their teeth into.

Glass is not the movie some may have been hoping for: the apex of Shyamalan’s return to form and a classic good-versus-evil showdown. To audiences who have proven how happy they are to be fed something designed by committee to have the broadest, most base appeal, this will be a shocking, infuriating movie. Rather than being a more grounded and stylized homeopathic antidote to Marvel films, Shyamalan has delivered a strange journey into the meaning and the hope to be found in comic books. This movie treats comics not as a narrative format to be recycled and adapted, but as religious myths to be followed and fulfilled. It is a single, impassioned vision that is totally uncompromising and utterly its own, comprised of layers and ideas that, while messily delivered, deserve to be turned over and explored.

Glass opens on January 18.