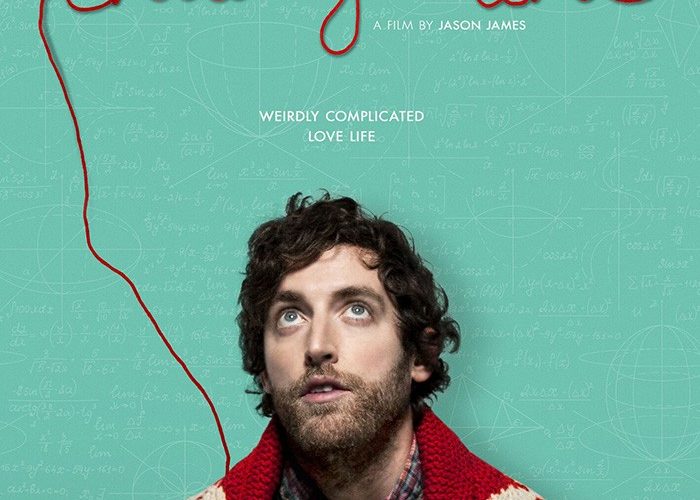

We’ve all asked the question: “What does our life mean?” Some of us do so out of curiosity, some out of boredom, and others from a place of desperation. Ben Layten (Thomas Middleditch) falls in the latter category after the wife he loved so deeply for many years leaves him for another man. He literally cannot cope with this turn of events, a long-standing bout with psychological issues and medications exacerbating any hope to find calm. So he does the unthinkable and resorts to suicide — multiple times. You could say the comical montage showing these attempts at the beginning of Jason James’ Entanglement is in somewhat poor taste, but the sense of exasperation with every near-miss failure is important. Something bigger than himself is deliberately leading him through.

Screenwriter Jason Filiatrault thankfully isn’t interested in making this “bigger thing” into God. It’s not even really a sense of spiritual fate either as Ben’s quest for answers comes from science with quantum entanglement as his guide. While he’s no longer suicidal, his depression remains like a weight on his chest of pure isolation. He therefore decides that something in his past went awry, that there’s some parallel timeline where he made a different choice and came out sane, happy, and complete. The notion that he can find this point and rectify what went wrong drives him forward with every new coincidence becoming a landmark to follow, study, and react against. So when his father drops a bombshell (Ben almost had an adopted sister), discovering her identity consumes him.

How would he have changed if he had a sibling? How would that interaction have affected his emotional stability, social skills, and confidence? The answer is a lot, but that doesn’t mean meeting her now at thirty will somehow provide the same stimuli — unless of course she is somehow his “complementary particle.” Even though they share no biological connection and have never met each other at any age, maybe the crazy circumstances behind their separation makes all that irrelevant. Since they were both meant to be Mr. and Mrs. Layten’s first child, they might share some sort of cosmic position. And when we realize he inexplicably ran into her (Jess Weixler’s Hanna) just days earlier, it’s difficult to deny that they were in fact destined to be together.

That’s what Ben wants us to believe. What I really like about Filiatrault’s script, however, is that its sense of idyllic fantasy isn’t without skeptics. While Ben embraces this strange scenario where his befriending his would-be sister blossoms into a potential romance, Tabby (Diana Bang) refuses to be so easily swayed. She’s his neighbor/friend — the former his label for her and the latter hers. It’s not hard to see she cares for him more than he’ll ever recognize, so we accept her almost maternal instincts to keep him grounded while Hanna seeks to chaotically break him out of his self-imprisonment. The result isn’t quite a love triangle since Ben is forever too oblivious, so Tabby unfortunately comes off as half-cooked sidekick for a majority of the runtime.

This is a shame since her dynamic with Ben is more compelling despite its obvious tropes. Even when Hanna is helping him see things he would never see without her, she remains a manic pixie dream girl to the nth degree. She’s the one who approached him; her romantic inclination overt from the start and therefore open to the audience assuming ulterior motives might be in play. Contrast this with the complex relationship between Ben and Tabby and we see the latter as a familiar yet enigmatic uncertainty. We see her as a guardian angel while Hanna is merely a welcome distraction from the doldrums of his heavy life. He likes Hanna’s fun (and it is therapeutic), but Tabby is always the one who picks up the pieces.

Everything ultimately goes exactly where you think it will even if the journey takes some detours. I don’t want to spoil anything, but anyone who watches a lot of movies should guess what’s happening early. James does a good job making sure certain revelations stand-up to what we’ve already seen — a blessing and curse since those breadcrumbs meant to be acknowledged in hindsight are often noticed in real-time. This isn’t a bad thing, though. You don’t need to be oblivious like Ben to appreciate where the road ends because Filiatrault has saved his strongest writing for the aftermath. Much of the film is forgettable in the sense that you’ve seen it all before. But where the jokes at the beginning feel tired, the drama at the end lands.

It makes me wish things were handled with more severity throughout. While Middleditch’s shtick is effective in its dryly-unassuming way, he proves he has the chops to go deeper into a character’s psyche beyond hard-luck Eeyore. For all the comedic trappings of the first two acts, everyone treats the rug pull into the third with authenticity. There are no easy answers or declarations of love; life is simply allowed to carry on in its messy and often confusing ways. Fate still lords over them all, just subtler than circumstances might have had us assume. Some moments are purely there for the juxtaposition gag (we never learn why Ben sees a child psychologist his own age — ruling out consistency in care), but they don’t distract from the film’s goals.

So don’t give up on Entanglement early. I’m not one to blindly look past the same clichés every romantic comedy pretends are unique, but this project does transcend its surface if you let it. Sit through the sitcom humor (“Your Dad should be fine … probably.”) and cringe when the script lets Bang down in its decision to draw Tabby as the meekly rejected without ever being rejected “nice girl” because things will get better for the overall tone and her character. The fantasy sequences of cartoon deer, public pool jellyfish, and kiss-ignited fireworks may seem hokey in the moment but their meaning will become less fickle in context with reality too. There’s more than meets the eye beyond that which the filmmakers intentionally hope you don’t see.

Entanglement is now in limited release.