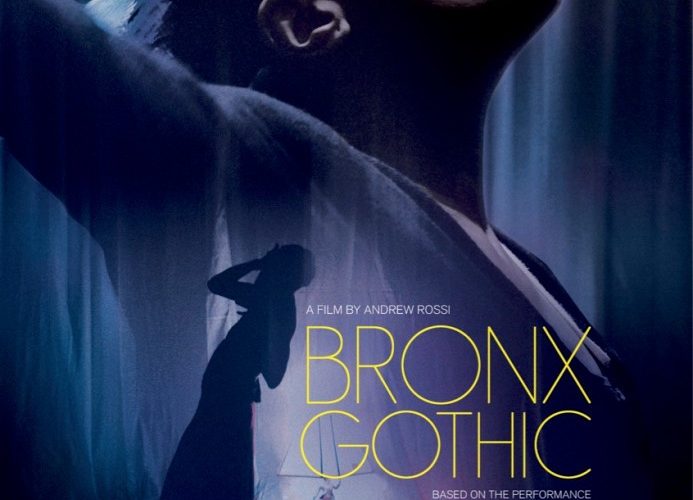

Cinematic depiction of performance art is a rich tradition, stretching back to the ‘60s as a form of documentation for what are, by design, live works. This lineage, if not directly continued, is implicitly referenced in Andrew Rossi’s documentary Bronx Gothic, which acts as a reflection of Okwui Okpokwasili’s solo performance piece of the same name. Pointedly, these two versions of Bronx Gothic – the picture and the performance – are deliberately separate. The film begins just after the final performance of the piece in the Bronx on its final tour, with an introduction of the piece as “written & performed by” Okpokwasili, before moving back to three months prior (just before the beginning of the tour) and displaying a traditional title card. This tension, among many other push-and-pulls, runs throughout Bronx Gothic, and serves to only strengthen both works — which are, in their own way, shifting, unpredictable, and passionately alive.

Bronx Gothic the performance piece is, as one might expect, the backbone of the film. Rossi takes the final tour of the piece in 2016 and weaves a surprising number of insights into Okpokwasili’s rationale and drive through the lens of three performances in Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and the Bronx, each of which takes up about a third of the runtime and are dedicated to a certain section of the roughly ninety-minute performance. The documentary’s narrative, such as it were, is defined by the piece’s, which concerns itself with a semi-autobiographical friendship between Okpokwasili as an eleven-year-old and her friend at that time, and explores notions of maturity, sexuality, and relationships – at that time, Okpokwasili represents a relative innocence and immaturity, while the friend represents a dangerous, explicit sort of experience. These are conveyed largely through handwritten letters between the two that are read aloud by Okpokwasili, but just as key are her often shockingly strenuous movements and rhythmic dancing – the first thirty minutes of the piece, beginning even before the audience walks into the curtained-off space, is solely dedicated to Okpokwasili dancing and essentially vibrating in the corner.

The rendering of these moments and many others helps illuminate what differentiates Rossi’s documentary from Okpokwasili’s performance. This writer has not seen the performance, but while the latter seems to be all about duration and her, if not strictly confrontational, then at least harrowing and disquieting interplay with the audience, the former achieves a different kind of effect and power that could never be achieved in the self-consciously spare, live-wire performance. The most notable of these is the incorporation of superimpositions, where Okpokwasili’s body is placed around the screen and audio from the more traditional documentary moments are placed over the performance. Other techniques are also prevalent: the use of subjective footage to illustrate her friend’s recurring dream of hell on Orchard Beach, the rapid-fire editing to punctuate a particular set of movements, the not-infrequent shots of the audience members, all of whom seem to be disturbed, uneasy, and more than a little moved in their own way.

But what makes Bronx Gothic (the documentary) so valuable is that even in the footage concerning Okpokwasili as a person, not as a performer – though it should be stressed that there is a very intentional blurring of the two in both piece and film – there is an undeniable interest and fidelity on the part of both filmmaker and subject, something not only evident in his willingness to let large sections of the piece play out. Whether Okpokwasili is shown holding court at a series of talk-backs about the piece, gratifyingly consisting of a diverse group of interested audience members, or sheepishly looking as her parents view part of her performance for the first time, Rossi never loses interest in this remarkable form of self-expression.

Bronx Gothic is not a filmed performance or a pat dissection of what, exactly, the piece comprises, but a hybrid of the best impulses of those two approaches. Importantly, Okpokwasili is the guiding presence and, for most of the film, the sole talking head; Rossi himself is only heard and seen in a few instances, and lets her expound unimpeded. What emerges is less a call for relevancy – a montage of various injustices ranging from the slave trade to the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter is the closest it comes – than something that feels and is thrillingly of the now, that looks back to a recent past in order to look to a personal future. Okpokwasili specifically states that the piece was inspired in large part by the then-impending birth of her daughter and her desire to provide something that would help guide her child, and it is all to the better that the film ends not with a grand statement, but a scene of domestic harmony between mother and daughter, between two black women at peace.

Bronx Gothic is now playing at Film Forum and expands in coming weeks.