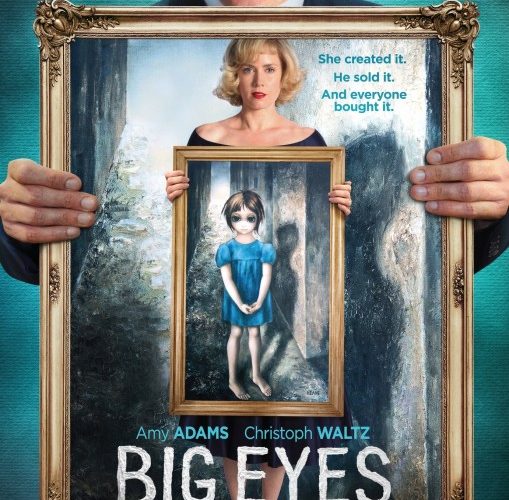

With a kind of quiet reserve, Big Eyes is a rare effort from the Tim Burton that plays it straight. The director wisely keeps the Burton-esque touches to a minimum, despite the temptation to explore the darker sides of Margaret Keane’s work, which appear to have influenced manga comics. The screenplay by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski (known for their biopics including The People vs. Larry Flynt, Man on the Moon and of course, Ed Wood) also plays it straight as a portrait of a marriage missing the psychological punch of Keane’s paintings.

While I took issue with Foxcatcher as an attempt to create psychological tension without a truly deep analysis of character psychology, Big Eyes is a far lighter affair. As a portrait of time and place, we follow two characters whom meet, fall in love and collude in a deception that ultimately picks at the core of Margaret (Amy Adams). The film is ultimately an art history story, tracing not the source of inspiration but the circumstances of production, exhibition and distribution. Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz) is first and foremost is a sales man and entrepreneur, seizing marketing opportunities at every turn, essentially working in the same mode as Warhol. Warhol, we learn from the film’s opening, admired Keane’s work for the same reason the Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl admires Gangnam Style.

Opening in a California suburb in 1959, Margaret and daughter escape a failed marriage to head for San Francisco. A painter by trade, Margaret is introduce to the neighborhood by her pal DeeAnn (Krysten Ritter) and soon finds herself sketching portraits at the park, where she stumbles across a friendly “painter,” Walter Keane. He’s a real estate agent with a talent for sales and business, and soon they marry and attempt to market their work to the San Francisco art community. The contemporary art world, embodied by gallery owner Ruben (Jason Schwartzman) and later New York Times critic John Canaday (Terence Stamp) pan the work as disposable. Water Keane, in an attempt to exhibit the work, coaxes a night club owner into wall space where the paintings, and Walter, find themselves the topic of intrigue in the local gossip rag. On the case is our occasional narrator Dick Nolan (Danny Huston), whom befriends the Keanes, loosing journalistic objectivity in the process — that is, until the film’s third act.

The lies start to collide within moments that are kept off-screen, including a confrontation between DeeAnn and Walter, as the latter grows increasingly violent after the deception has spawned an industry that includes posters, post-cards and a gallery. In one of the film’s strongest sequences, Margaret, while shopping in an A&P passes a row of Campbell’s soup cans, walking down an isle towards a monstrous display of Keane merchandise. This scene is essentially the most Burton-esque, but here he takes a somewhat lighter touch in a story about limited self-expression. An issues film that takes on the art world, it contains very few scenes of the glamor associated with the world; after all, in this portrait Margaret and Walter live a more conservative life than the New York scene. Older and with children and responsibilities, Walter unlike Warhol is not a cult leader — his method of manufacturing work is limited to his wife.

Chronicling the ups and down without a heavy psychological analysis — and surely some must be left in Margaret’s later work — Burton places us in the shoes of Walter: tasked, for the press, of figuring out why a grown man might continually paint pictures of little girls in pain. An effective portrait of the influence of art in the age of mechanical reproduction and creation on demand, with a light touch Big Eyes is a personal triumph wrapped within a critique of conceptual art.

Big Eyes is now playing nationwide.