A word of caution to the romantically inclined sci-fi buff: About Time is not a time travel movie — it’s a Richard Curtis movie. If you have ever entertained the possibility of swimming against the current of your own time stream and remaking key choices therein, then you’ve likely put more thought into this premise than Curtis did. The very conceit of the time displacement is treated with about the same speculative rigor as the remote control in Adam Sandler’s Click. This doesn’t make it a bad movie, but it is a real missed opportunity. This is one of those times Curtis might want to replay and fine tune.

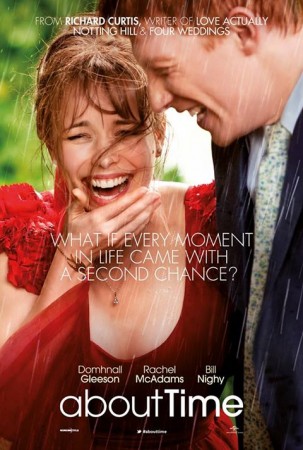

Of course, like his previous efforts, the film has been impeccably cast. Affable Irish ginger Domhnall Gleeson is Tim, a would-be lawyer who, at 21, is dropped a bombshell by his quirky dad; the men in his well-off family line have always had the ability to travel in time. Bill Nighy, who effortlessly steals every scene he’s in and makes countless others better by association, plays Tim’s Dad, and as he explains it this process only works backwards and only in your own lifetime.

As it’s so eloquently put by the blissfully understated Nighy, “You can’t kill Hitler or shag Helen of Troy.” Too bad he had to say that, because I’m now doing two things counter-productive to enjoying About Time. One of them is imagining the movie where Gleeson and Nighy set out to do both of the above-mentioned activities, and the other is recalling Nighy’s slight-but-emotionally resonant moment as a museum docent in the Nu-Who episode, Vincent and the Doctor. Ahem, moving on.

There are a wealth of things you could do with this ability, even if it’s also required you do your best to hide your departure. Tim often adopts a C.S. Lewis meets Clark Kent approach to this subterfuge, stepping into a wardrobe or dark corner so he can whisk off and replay some fumbled bit of personal history. For Tim, it’s mostly used in romantic interludes, when he’s got to seriously redo something inane he’s said or refine something else he’s mangled because of lack of experience (he tries out a sexual encounter until he’s a master the first time through).

Tim also meets cute and perky Mary (Rachel McAdams, in more spot-on casting), an American who babbles about Kate Moss and bangs, and he decides she’s the one. If we’ve learned nothing else from movies like this one and The Time Traveler’s Wife, it’s that genetically inclined time-traveling males are cosmically drawn to Rachel McAdams. If it seemed rather creepy that Eric Bana visit a child-age version of his eventual wife in that film, Tim doesn’t get off scott-free in the morality department either. He fails to ever inform his love of the constant time-fiddling he’s done to shape his perfect reality. At least Bana was an out-of-the-closet time traveler as far as his family was concerned.

But of course that perfect reality isn’t achievable anyway. How could it be? Our bad decisions—or those decisions we see as bad—were often made with the best information we had at the time. A decade, year, week, or even hour after said decision doesn’t necessarily mean that because we feel regret, we have any more of an informed understanding on how to make it truly better. Tim learns this through a number of other painfully obvious, poignant and sometimes uplifting things. Seize the day, cherish and enjoy friends and family even when they drive you nuts, nothing lasts; it’s all here and delivered with the same tact as that cue card sequence involving Keira Knightley in Love Actually. Typical of Curtis, it isn’t these broad proclamations or even the slight and airy central love story that registers. It’s the side characters and smaller moments of About Time that ring true.

Gleeson is a nice change of pace for a romantic lead, and he embodies Tim’s shyness and gentle good-nature, even in the face of the wrong course of action. McAdams is scrumptiously adorable, but that’s about it for her character, although she wears it incredibly well. You came to see them — they are on the poster — but what you should really know is that it’s in Nighy, Tom Hollander as Gleeson’s scathing playwright and Lydia Wilson as offbeat sis Kit Kat that the movie finds most of its energy and heart. Just as the family and friends surrounding Hugh Grant in Notting Hill resonate more deeply than his fop caught in Julia Robert’s headlights, so too does this trio outshine the Gleeson/McAdams plot, even when they represent well-worn Curtis clichés.

Nighy, particularly, is very good in his scenes with Gleeson, and together they threaten to turn the movie into a love story of a far more refreshing kind; the familial bond between a father and his son. Here’s where the big downside of About Time comes in; it never truly commits to its premise or those tastier pieces. Yes, we know the time travel is just a vehicle to get to these big themes Curtis wants to emphasize, but once introduced, it catches our interest and imagination. Given that, it’s grating when all elements of logic or basic consistency go out the window. The movie doesn’t play fair because it doesn’t think it has to. It believes in love, but not the story it is telling.

From there, it’s entirely up to you the viewer to decide if About Time has provided enough value to make the trip to the cinema worth your time. Curtis, even when he over-eggs the pudding, can be very good. He’s even very good in About Time, but not all the time, and not nearly enough to ensure that we aren’t considering winding back our own lifetime so we can strategically watch just the good parts.

About Time hits wide release today, November 8th.