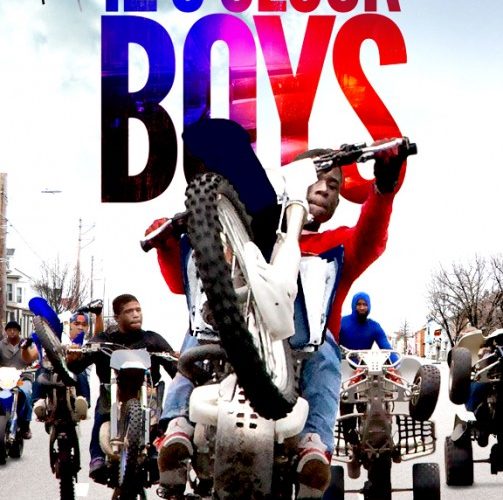

When we first meet Pug he’s a bright 13-year-old living in a rowhouse in Baltimore, spending his time idolizing the dirt-bike gang that tears and zips through downtown. Lotfy Nathan’s 12 O’Clock Boys features the titular daredevils and their hair-raising bike stunts—they are so named because they ride with their bike handles pointing vertically like the hands of a clock—but its true focus is this young man, an innocent pulled and pushed by the allure of the bikers and diminished options he faces at home. When some friends suggest that the dirt biking is a positive activity, and a far superior alternative to drug-dealing, the lack of nihilism in the thought keeps us open-minded even if unspoken doubts remain.

Nathan could have approached the tale as a condemnation of the thrill-seeking gangs and their dangerous practice of hurtling through traffic to arouse cops to chase, or as a moral indictment of the poverty and limitations that have left kids like Pug with few choices. Instead, he’s achieved a journalistic synergy that looks at all angles of Pug’s environment and observes without judgment. The result is a captivating and insular look at a culture that most know little about, driven by an urgent, surging life that stands apart from the similarly themed portrait of the city we saw in David Simon’s The Wire.

Nathan followed Pug over the course of three summers, starting in 2010 and ending when the boy was sixteen, a teenager who’d grown rougher, more surly and determined to test his skills alongside the bikers he’d enviously watched for years. This transformation in Pug is one of the most interesting aspects of the film, chiefly because what seems inevitable when we meet him still feels abrupt when we see it transpiring; it’s easy to yearn for more, while realizing that his belief in the ‘Boys’ as his one shot possesses a certain realist allure. Juxtaposed against Pug’s home life, with his mother Coco—formerly an exotic dancer—and his brothers, are the antics of the 12 O’Clock Boys themselves; a spectacle in and of itself, that deftly captures both Pug’s admiration and the inherent danger and seduction involved.

For Pug, a talented rider on his own terms, the bikers’ skill and recklessness form a symbiotic mission that he disturbingly gloms to; it’s all in for the sake of derring and thrills, and spitting in the face of death and authority is all part of the fascination. As time goes by, Pug’s obsession leaves little space for developing character and we watch him grow from innocent to hard-edged, replacing curiosity with profanity and arrogance, even going as far as to kick at the dog he once adored. His mother desperately hopes he will take his love for animals and become a vet, but he’s at a lack for any other role models in his life. An older brother who he looked up to dies suddenly from an asthma attack, and it’s not hard to see where Pug’s coming from when he says, “Tomorrow is not promised. I could die tomorrow.”

That mindset isn’t as philosophically thoughtful as it is dismissive and resigned, used to excuse the likelihood that Pug himself might encounter serious harm at the wheel of his bike. Nathan never shies away from the criminal aspect of the bikers or the escalation that happens to both riders and pursuing police when the chases get underway. For any of us who have had the experience of seeing the real Boys up close while making our way through the city on a weekend, it resonates when Nathan also observes the destruction left in their wake. In fact, the filmmaking on 12 O’Clock Boys is masterfully even-handed and fastidiously detailed, placing us at a kaleidoscopic vantage point that lets us see several perspectives at once, even as most of these characters are firmly grounded to one limited trajectory.

It’s a strong and bold first feature, and although it doesn’t necessarily offer solutions for any of Pug’s immediate issues, or offer him an tempting alternative to joining the Boys, Nathan also firmly suggests that there aren’t any easy answers available. As a portrait of Baltimore life the film accomplishes it’s goal, illuminating a world that can be at once both hopeful and oppressive, dangerous and empowering, encapsulated through the eyes of one boy living through it. When the final frames play, we are left wondering not just what Lotfy Nathan might do next as a director, but what will become of Pug, and where his journey may lead him. I’d be up for seeing this 12 O’Clock boy down the road, when the hands have turned again.

12 O’Clock Boys is currently playing in limited release.