When first approaching Marlon Riggs’ small yet impactful filmography, it is impossible to ignore the breadth of documentary modes utilized to tell his stories and shed light on the experiences of gay Black men, fluidly gliding between multiple approaches to explore various facets of storytelling. With his entire oeuvre now on the Criterion Channel, Riggs’ extensive prowess for wielding the documentary as a force for compassion is available for all to see.

I was first introduced to Riggs’ work through his made-for-TV documentary Color Adjustment (1992), an exhaustively well-researched non-fiction film exposing how TV’s many attempts to assimilate Black characters on screen, and therefore into white homes, has time and again missed the mark. From the calcified stereotypes of Amos ‘n’ Andy and Beulah to the lack of culture seen in shows such as Julia, TV executives continually misjudge appropriate portrayals. Upon revisiting, though, I was struck by Riggs’ ability to treat the TV as not merely a medium but an empathetic figure in the growing conversation. While Riggs accuses and indicts TV for its outdated notions of Black life in America, he also sympathizes with those who have attempted a more worthwhile integration. Color Adjustment spotlights shows like East Side, West Side that attempted to tackle the “Race Problem” of the ’60s by inviting viewers inside lower socio-economic neighborhoods that weren’t otherwise shown on TV at the time. With characters calling out their counterparts for their implicit racism, the show was quite ahead of its time—evidenced by it being canceled after one season. In the same way, Riggs devotes just as much attention to the assimilated Cosby Show as he does to its contemporary and more realistic depiction of Black life, Frank’s Place. Both Color Adjustment and Riggs’ first professional documentary, Ethnic Notions, show a filmmaker utilizing an expository mode of documentary filmmaking that focuses more on information than aesthetics. What these two projects lack in aesthetic artistry they compensate for tenfold in their ability to convey empathy to the viewer.

It is not the expository documentaries, though, that Riggs is known for, but rather his performative and poetic movies. In one short, Anthem, Riggs weaves together erotic images of Black men and superimposes them on patriotic images that attempt to appropriately integrate Black queerness through the use of Eisensteinian, Constructivist editing techniques. In another short, Affirmations, Riggs utilizes observational documentary camera techniques to zero in on the African American Freedom Day Parade that runs through Harlem. Alongside the Black pride banners, Riggs captures those in the parade who are focused on the intersectionality of Blackness and queerness. Riggs uses his sound design to convey a cacophony of voices within the parade so no chant can be heard distinctly, until one man shouts from the crowd at the gay Black men, “There are children here!” Riggs here, and in the majority of his work, focuses on the idea that many gay Black men not only feel alienated from society as a whole, but Black society as well.

Tongues Untied

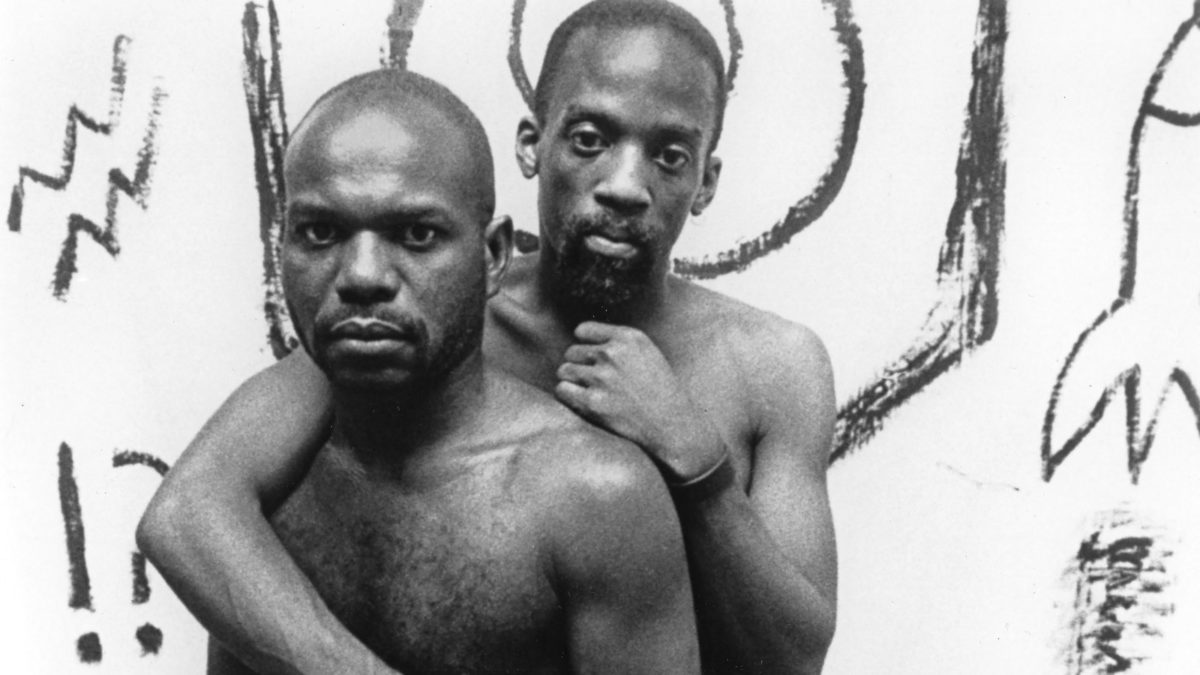

The themes and footage of Affirmations expand into a much larger documentary—arguably Riggs’ magnum opus—Tongues Untied. At one point poetic in its use of aesthetics and imagery and at another performative in Riggs utilizing his own storytelling onscreen, Tongues Untied is a true deconstruction of society’s interpretation of Black queerness. Riggs takes the opportunity to pontificate how difficult it is to be a gay Black man in America, being so violently thrown across the identity and emotional spectrums, never really knowing where you fit in and belong. Using footage from Hollywood and stand-up specials by Eddie Murphy, Riggs also shows the difficulty of even fitting into the Black community and feeling like an outcast there. One of the documentary’s most compelling points comes towards the start as Riggs sets his thesis: against a black backdrop, an unnamed naked Black man moves across the frame, almost dancing, as the camera follows him. Riggs is calling on the early cinematic documentation utilized by Edison in the Black Maria. As people were still understanding how the cinema and moving pictures worked, filmmakers and audiences were fascinated with just watching and understanding how bodies moved on screen. This plays out with the famous Eugen “The Strongman” Sandow and Serpentine dances of Loie Fuller. Riggs is attaching Black queerness to this tradition: as we deconstruct our preconceived notions of race and representation on screen, Riggs wants us to revert back to our most primal, cinematic form, which is merely to observe and understand.

Riggs is not merely a great documentarian because of the subjects he chooses to spotlight, but also because of his mastery of the form. It is in this fusion that made his work so important in its time and, even more so after death, of grave importance now.

Race, Sex & Cinema: The World of Marlon Riggs is now playing on The Criterion Channel.