Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2024, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

It is almost impossible, or so it seems to me, to have a conversation about the films of 2024 without first considering 2014. That year, many of us wondered where cinematic language was headed, especially given our recent experiences: Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue is the Warmest Color (2013), Michael Haneke’s Amour (2012), and the revolutionary Terrence Malick’s adventure The Tree of Life (2011). What more was there to be said, if anything at all? But then, Paweł Pawlikowski presented Ida, a quiet yet audacious black-and-white, 4:3-ratio, minimalist film, and we thought the possibilities for great cinema were infinite, and that we really could have a masterpiece every year (naturally, we were wrong).

Ida, in any case, was and still is, something more than a masterpiece: it’s a classic, and as such, a reminder that good cinema, like good art, should always be simple. The trouble is that simplicity is hard because, as some French philosopher would say, “La simplicité n’est pas la simplification” (Simplicity isn’t simplification). The night I watched Ida for the first time, it was in a tiny movie theatre in Trastevere (Rome) that has since ceased to exist. The room was crowded, and I sat a couple of rows behind my friend who had purchased the ticket for me (I still have that ticket, and I’ll never stop thanking her). I believe that night made me aware of what I’ve always known to be true inside me: that small things can be powerful, that your almost invisible existence matters in relation to its truthfulness, and that if you can find it, you should hold on to that glimpse of truth despite living in a world that provides you with alternate realities made of glamor, and advertisement, and comfortable lies. Resisting consumerist society, Pasolini warned us from the very beginning, is far more difficult than resisting fascism.

Ida also made me think about the end of Federico Fellini’s 8 ½, when the film critic addresses the protagonist: “There are so many superfluous things in the world already,” he says. “No need to add chaos to chaos. We’re smothered by words, images and sounds that have no right to exist, that come from the void and return to the void. Of any artist, truly deserving of the name, we should ask nothing but this act of faith: to learn silence.”

After winning the Lux Prize, Pawlikowski noted: “(Ida) It’s not a film about the Holocaust. It’s about faith, yes, faith in general, but also faith in Marxism, the need for faith. Of course we all have the need to believe.” What he was trying to say, I think, is that sometimes to talk about something, it’s better to talk about something else. Pawlikowski also belongs to a generation that strongly believes art should suggest and never explain. Cinema, as we once knew it, was a space for evasion, not a prison of empty concepts. Authors understood that the risk, when you want to say too much, is to say absolutely nothing.

“Cinema is a question of style, and style is a moral issue,” affirms the cinephile in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution, staring at the protagonist in anguish over something as seemingly frivolous as love. He continues: “I watched Vertigo eight times. Journey to Italy fifteen, and you can live without Hitchcock and Rossellini? You say that Resnais and Godard make entertainment films. Une Femme est Une Femme is more ‘engaged’ than the films of De Santis or Lizzani, and even Franco Rosi. Things happen in life which we don’t understand at first, but which are important and change us. A tracking shot is style, for instance, but style is a moral question. I remember a tracking shot by Nicholas Ray of 360°, which is one of the highest moral moments, and thus ‘engaged’, in the history of film. A 360° of morality. Remember, Fabrizio, one can’t live without Rossellini!” Once again, a generation that understood any conversation about style and meaning is pointless, simply because style is meaning.

Today’s films have become increasingly didascalic. Following new pseudo-political trends, writers and directors seem to have forgotten that their duty is not to educate the audience but to make good films. A good film can, of course, eventually educate the audience, but that’s another conversation— and not one for today, where it is indeed difficult to tell the difference between a film, a music video, a fashion show, an overlong Saturday Night Live sketch, or a series of Instagram stories. Personally, I’m a big fan of mixing up the medium, when the result is The Zone of Interest, though sadly, not everyone is Jonathan Glazer. One wonders if, in a few more years, we’ll ask ourselves whether replacing authors with influencers was a great idea after all.

Meanwhile, we should ask ourselves: “In the past 10 years, have I seen a tracking shot that changed my life?” Personally, I have—in Godland (Hlynur Pálmason, 2023). I trust it, it speaks to my education, and I’m going to hold on to it for the times to come. I hope you’ve got one too, and I hope that you won’t feel bad about watching it over and over again. And if you don’t have one, I hope you’ll consider going to the movie theater, on these winter nights, and checking out more films. Sometimes special things are hidden in unexpected places. I hope to see you at the movies.

Here are 15 films whose stories made me reflect on life in (Late) Capitalist societies—films that struggle with the question of language, both in terms of identity and relationship, which is the possibility of sharing a moment of truth amidst diversity.

First-Viewing Honorable Mentions:

- Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the 60s in Brussels (Chantal Akerman, 1994): Akerman might be the only director who completely achieved her intention of adapting Existentialism to the (either big or small) screen. This television film is also a masterclass in camera work—very much needed.

- Queen of Hearts (May el-Toukhy, 2019): A film that exposes the drama, frustrations, and little lies of the bourgeoisie, permeated with subtle intelligence, and a sort of cold fury. Terrific!

- Origin (Ava DuVernay, 2023): A very ambitious project, executed with meticulous filmmaking, and an extraordinary level of care for its subject matter.

- Expats (Lulu Wang, 2024) is one of the things I enjoyed the most this year. Wang’s ability to be quirky and funny until she goes full drama makes her irresistible.

- Il grido (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1957) came back to theaters in a gorgeous 4K restoration. It’s a brilliant exploration of Italian patriarchy through a man’s inability to be sentimentally independent from the woman he believes to love, and therefore from any other woman. A must-watch.

Top 10 of 2024:

10. Girls Will be Girls (Shuchi Talati)

A journey of sentimental education for both a teenage girl (played by Preeti Panigrahi) and her mother (Kani Kusruti), who vie for the attention of the same young man (Kesav Binoy Kiron). Talati builds an interesting narrative structure around the effects of female sexual repression and confinement in Indian society, while also provoking the audience into uncomfortable questions about female freedom—and not just a formal one—everywhere else. How much does the presence of a man still define a woman’s life? Are we ready for real change? And is the possibility of freedom so frightening, that we would rather continue living in slavery? The film does not answer, but the questions stay with you. Sweet.

9. Sebastian (Mikko Mäkelä)

Notably, Marguerite Duras believed that publication is prostitution, so the story of a young writer (played by Ruaridh Mollica) who publishes short stories in Granta and subsequently decides to try sex work seems particularly brilliant to me. Publishing has also changed significantly since Duras’ time, turning into an industry where the quality of writing isn’t exactly the criterion that decides the success of a book, let alone whether a book even gets published. Mäkelä chose an efficient way of illustrating the compromises young people must make to be seen or heard, and how the conversation often centers more on the writer’s image, rather than on their real skills. I especially appreciated the final, positive note, when the protagonist meets someone (Jonathan Hyde) willing to help him with no expectation of anything in return. While this may not happen in reality, it’s nice when filmmakers remind the viewer that we can all be better, if we only choose to be.

8. A Traveler’s Needs (Hong Sangsoo)

Hong Sangsoo’s decision to craft a story with very few means results in a simple tale of resistance to financial capitalism, which reveals itself to be very powerful. To me, this is above all the story of a friendship between a 20-year-old Korean student (Ha Seong-guk) and an older French woman, Iris (Isabelle Huppert), who becomes his roommate after deciding to move to Seoul with no money and no profession. Since neither of them seems to fit into society, they quickly bond, and Iris begins giving unusual French lessons. The money she makes the first day, she gives to the boy because, she says, he’s the one who’s helped and advised her. His mother stands in for societal standards, but this story of two people of different ages who can’t do anything for each other because they can’t even help themselves, is refreshing. Perhaps the main theme of the film is that real relationships are only possible outside the market. Perhaps we should all give it a try.

7. The Shadowless Tower (Zhang Lü)

A divorced middle-aged food critic, Gu Wentong (Xin Baiqing), seems to realize that life in adulthood might just be boredom and regret, but also, that it is totally fine to navigate one’s failures, and insist on living despite it all. There’s an old Chinese song that the children at the Chaoyang Welfare Centre sing: “Willow trees on the riverbank sway wildly in the autumn breeze. All the leaves have fallen, leaving only bare fragile stems. Remembering those days when the green grass was lush and the spring light was warm. Nowadays all we have are bleak, cold, and dark autumn days. Blustering winds and pouring rain. Everything in sight has completely changed beyond recognition. Has completely changed beyond recognition. We reflect and look back in unbearable sorrow.”

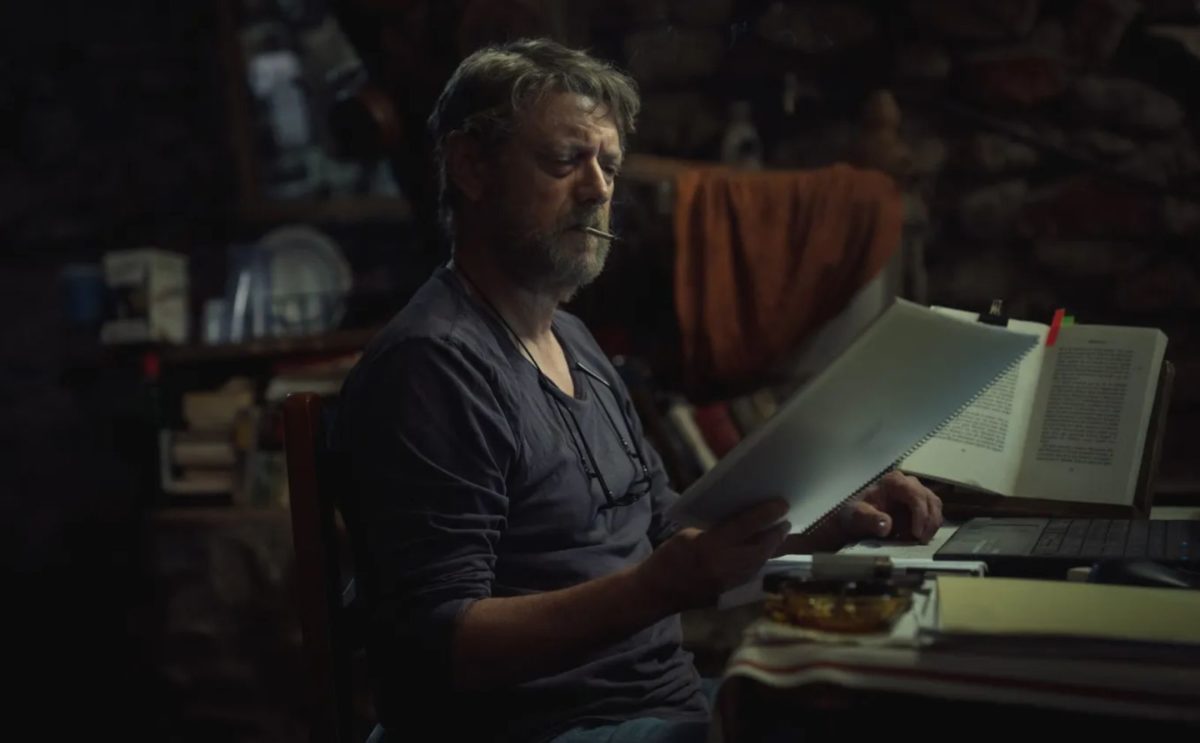

6. Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice)

I guess this film hits you differently depending on how familiar or obsessed you are with The Spirit of the Beehive. Víctor Erice may not make many films but when he does, one surely notices. Fifty years after his masterpiece, he returns with a quiet yet inexorable rumination on the meaning of life and, why not, perhaps the death of cinema as “the great folk art of the century” (Erice). “As opposed as it is today,” he notes: “a consumerist good dictated by the market of television. Filmmakers like myself are marginalized not because we want to be, but because we’re forced by this system.” As in a Proustian epic, Ana Torrent, the little girl from The Spirit of the Beehive who enchanted generations of cinema lovers, also returns—only this time as a mature woman. Unaltered are both her charm and her eyes and, I suppose, as we neared the end of the film, her “Soy Ana” made us all squirm. Remember? “If you’re his friend, you can talk to him whenever you want. Close your eyes. And call him. Soy Ana, soy Ana…”

5. The Last Showgirl (Gia Coppola)

This is one of my favorite pieces of filmmaking of the year. It is also a reminder that directors, if they truly are such, should always be able to work with very limited budgets. Sometimes, family projects with tiny crews and the opportunity to really focus on the craft are the best. Gia Coppola filmed a 16mm marvel, from a finely drawn story (written by Kate Gersten) and gorgeous costumes (designed by her mother, Jacqui Getty). The film was produced by her cousin, Robert Schwartzman. Pamela Anderson delivered a standout performance, and Jamie Lee Curtis is perfection. If, when in Vegas, you’ve ever wondered what life is really like for people who work in casinos and show business, this film is for you. If you’re an admirer of Jacques Demy’s Bay of Angeles, this film is definitely for you. It is also a tender mother-daughter story and, at the same time, a resilient testament to one’s freedom, despite the duties and responsibilities one feels toward those they love.

4. Flow (Gints Zilbalodis)

A troubled odyssey for a charming kitten and his animal allies—perhaps soon-to-be friends—in this experimental gem, whose style is reminiscent of both Terrence Malick and Apocalypse Now. Waking up in a world devastated by a major flood that threatens life on Earth, the group, formed by different species of animals, is forced to cohabitate on the same boat and work as a team despite their inherent differences. Flow isn’t only a call for environmental action but also a testament to the beauty of life when we are able to see it in its essential form. Because in the end, as humans, we’re most of all animals.

3. The Settlers (Felipe Gálvez Haberle)

When you want to be reminded of what real cinema looks like, you can safely turn to Chilean directors. Felipe Gálvez Haberle teams up with Italian cinematographer Simone D’Arcangelo for his first feature, a stylish domestic Western based on yet another forgotten chapter in the history of the colonization of indigenous people. Three horsemen—a mixed-raced (Camilo Arancibia), a Texan mercenary (Benjamin Westfall) and a British former soldier (Mark Stanley)—are sent into a genocidal mission that will affect each of them in very different ways. Here is a film where evil characters remain evil, and the relentless resilience of survivors is shown through imperceptible looks and gestures, right up until the very last shot. The cast is perfect, the script is sharp (Antonia Girardi, Felipe Gálvez Haberle, Mariano Llinás), and the cinematography, costumes (Muriel Parra), production design (Sebastián Orgambide), music (Harry Allouche), and sound design (Duu-Chih Tu and Tse Kang Tu) are impeccable. This is one film to be remembered.

2. Nocturnes (Anirban Dutta and Anupama Srinivasan)

I was fortunate enough to have had the chance to watch this exquisite documentary in a movie theater, which gave me eighty-two minutes of pure pleasure. Co-directors Anirban Dutta and Anupama Srinivasan crafted a heavenly film with a truly emotional cinematography (by Satya Rai Nagpaul), and a uniquely evocative sound design (by Tom Paul and Shreyank Nanjappa). There’s something mysterious and magical about this story, perhaps even divine. Ecologist and postdoctoral researcher Mansi Mungee, and her assistant, Bicki, seem to have found the secret to happiness, which consists in living in the Eastern Himalayan forest, studying the behavior of the moths. Moths are important, we learn; they contribute to the equilibrium of the forest. Though some of them live no more than two or three days, they’ve been on Earth for almost 300 million years! That’s before dinosaurs, and even flowering plants. Moths have survived five mass extinctions, mastering and shaping the notion of Time. Who are we in comparison to the moths? How dare we breathe their same air?

1. All We Imagine as Light (Payal Kapadia)

The first tracking shot through the streets of Mumbai, accompanied by the voices of anonymous migrants, immediately tells us that a great director is speaking. She’s speaking also through the voices (off-screen) of her brave protagonists—two nurses in their early and late thirties who share the same apartment, Anu (Divya Prabha) and Prabha (Kani Kusruti), and an older, newly retired hospital cook, Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam)—and through the city’s lights at night as well. The lights serve as a focal point amidst the chaotic movements of those who inhabit the city. Anu has a lover with whom she can’t really make love to, while Prabha can’t confront her suitor, a doctor who writes poetry for her, as she’s still married to a man who migrated to Germany. Parvaty, meanwhile, is forced to return to her village. Is leaving the city a defeat or a victory? All We Imagine as Light can be read like a long poem sustained by various voices, all ultimately belonging to the voice of the author. Like in a poem, a few clear yet unimportant details will remain with us. For me: the numb faces of those who take public transportation, the enchanting golden jewels touching the skin of the women as they work, cook, make love, and the flickering lights that pay no heed to the struggle of ordinary people’s life.