Growing up in a Catholic country where we were instructed to say our prayers each night before going to sleep, I always found myself dreading the moment when I had to address a man in the sky to help me forget my troubles and get happy. As a queer child, I wondered how a straight man, holy or not, would understand my concerns when the very essence of who I was represented something meant to be eradicated from their organization and from society.

Things changed after I watched The Wizard of Oz. In the young Dorothy’s search for friendship, community, and a road to follow back home, I found a kindred spirit. In her tremulous determination, I found the courage to be myself. In her witty problem solving I came to terms with the idea that brains are best put to use when they’re at the service of improving society. In her profound love for the people she meets in Oz I realized that even the most battered of hearts can make room for some more compassion.

Then every night, during prayer time, an image instantly materialized in front of me, that of 16-year-old Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale asking to be transported to a place where “trouble melts like lemon drops,” where bluebirds flew and escaped the sorrows below. Somewhere over the rainbow.

I learned about Garland’s history, and how she had overcome tragic marriages, a corrupt studio system, constant loss and heartbreak, and eventually had succumbed to drug addiction. Even in death, we could see her generosity in how she had served as an inspiration for LGBTQI activists who rioted at the Stonewall in NYC, when policemen interrupted grief over her passing, to enforce inhuman laws.

After that whenever I felt the need to reach out to a holy figure, it was Garland I sought, often asking myself WWJD, “What Would Judy Do?”

The older I grew, the more grateful I was for Dorothy and for “Over the Rainbow”, but the one thing I could never shake off was Garland’s sadness in that scene, the more I watched the film–which by now I’ve seen over 100 times–the more evident her sorrow became, and as I turned into a full-on Garland obsessive watching all her films, collecting all her music, it never escaped me that when I heard her sing she activated something inside my soul, while her own always seemed to be on the verge of being shattered.

I wanted to help her in the same way she’d helped me. I went from praying with Judy, to praying to Judy, and eventually praying for Judy.

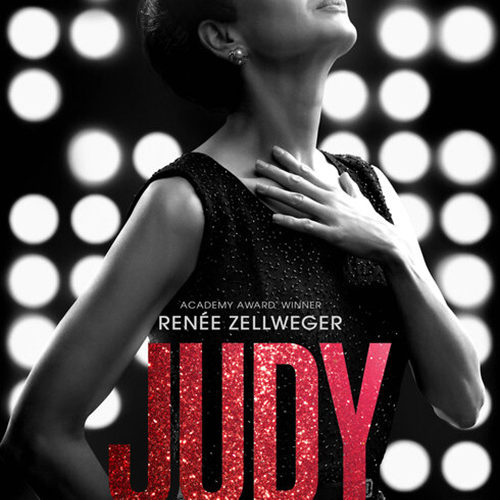

And so, if Judy Garland is a religion, in Rupert Goold’s Judy, Renée Zellweger is the faithful priestess leading us as a devoted choir, as attentive churchgoers, and above all, inviting us as human beings to open our hearts to an icon that gave us so much and asked so little in return.

The biopic based on Peter Quilter’s play End of the Rainbow, splits the character in two, one the bright-eyed young Judy (played by Darci Shaw) in the midst of shooting Oz, the other Garland, the living legend, 30 years later played by Zellweger.

Intercutting scenes from one Judy to the other, we see moments in which the young Judy endures psychological abuse at the hands of Louis B. Mayer, who makes fun of her weight, appearance, and background, insisting that young women like her are a dime a dozen. We see how the strict regimes of pills, no food, and no sleep led the young woman to seek an escape from the set of Oz, as she shot one of the most beloved films of all time. And of course how this created Garland’s lifelong dependency on amphetamines and barbiturates, which led to her untimely death in 1969 at the age of 47.

Although there is nothing new or inventive in the film’s storytelling techniques and from an aesthetic level it would be hard to tell Judy apart from the myriad prestige biopics that arrive in theaters during the fall, the film’s undeniable power rests in the miraculous performance by Zellweger.

With no offense to Shaw, who is lovely as the ingenue Judy, her scenes become redundant with just one look into Zellweger’s eyes, who plays the legend in 1968 as she fights to keep custody of her younger children, retain the vestiges of her career, and quite simply stay alive.

In many ways, Zellweger’s performance turns the film into an against-the-clock thriller, in which we desperately hope she will be able to find solutions and melt all those troubles like lemon drops. Sadly, we know better, and so Zellweger’s delicate work transforms the film into something like a heavenly audience with a beloved figure, making Judy more of a seance than a movie.

Pretending that Zellweger “becomes” Judy Garland would be ludicrous, especially considering she also sings some of Garland’s most beloved tunes in her own voice, rather than lip-syncing. Garland’s otherworldly vibrato remains inimitable, the gift she was given by the gods to share with mortals, but in attempting to evoke Judy’s spirit through her own undeniable gifts, Zellweger does something that actors in biopics often abstain from, she dares us to see her and the character she’s playing.

The actress shines brightly in numbers like “By Myself,” which Goold shoots in what seems like one cut, not the chaotic sequences filled with interminable two-second shots we’ve become used to in modern musical numbers. Unsurprisingly scenes in which she sings as Judy are the ones that become most alive, like Garland, Zellweger is an entertainer above all, and it makes sense that she would be at her best in her habitat.

Although actors who specialize in mimicry and chameleon-like performances are often praised and showered with gold statuettes during the late winter, there is nary room for actors who let us see them as they take on well-known figures. It’s almost as if we demand erasure of self in order to portray someone else, as if two souls could not co-exist at once.

This is why I gasped with delight during a moment in which Judy Garland reacts onscreen and I recognized a barely-there shrug as Renée’s own, the one I came to fall in love with in films like Bridget Jones’s Diary and Chicago, among others. Or why I was so moved during a scene in which Renée’s own voice comes across as Judy gets into an argument with her lover Mickey Dean (Finn Wittrock).

Merely a few years ago, Zellweger, who had risen to the top of stardom became a tabloid punchline as headlines wondered if her career was over, or whether she had plastic surgery done, the way in which the industry punishes women who dare succeed and that most sinful of things: age.

So to see Zellweger back onscreen, in a film that turns her work into the centerpiece isn’t only rewarding for fans of the actress or fans of the legend she plays. Zellweger was born two months before Judy Garland passed away in 1969, so at age 50 the actress gets a chance at life that Judy never had. She outlived her by three years, and in Hollywood that’s a lifetime. Although Zellweger sings some of Judy’s most famous songs, her performance itself is a version of Stephen Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here.” Good times, bum times, she’s seen the gamut from A-Z and she’s here.

For a woman to survive in an industry that loves to destroy its female idols, and deliver the best work of her career at a time when many hoped she would’ve retired is a wonder. As Garland, Zellweger celebrates her wrinkles. Her maturity, her lifelong experiences form her performance, like the rings of a tree when it’s been cut, and I simply can not think of a better tribute to Judy than this.

Judy is now playing in theaters.