Mia Hansen-Løve once spoke of her corpus like a home: “I think of my work on two levels: the film itself, and then the film as a part of a larger whole. A house that would be my work. Film by film, I’m trying to build my house higher and bigger.” In One Fine Morning she returns to Paris, the city where she was born, with a work as warm as a summer stroll and just as melancholic. Playing out on sunlit days and in casually cultivated Parisian apartments, it is yet another bittersweet slice of life from a director whose cinema has always felt at its most comforting, most profound in the familiar side-streets and boulevards of the French capital.

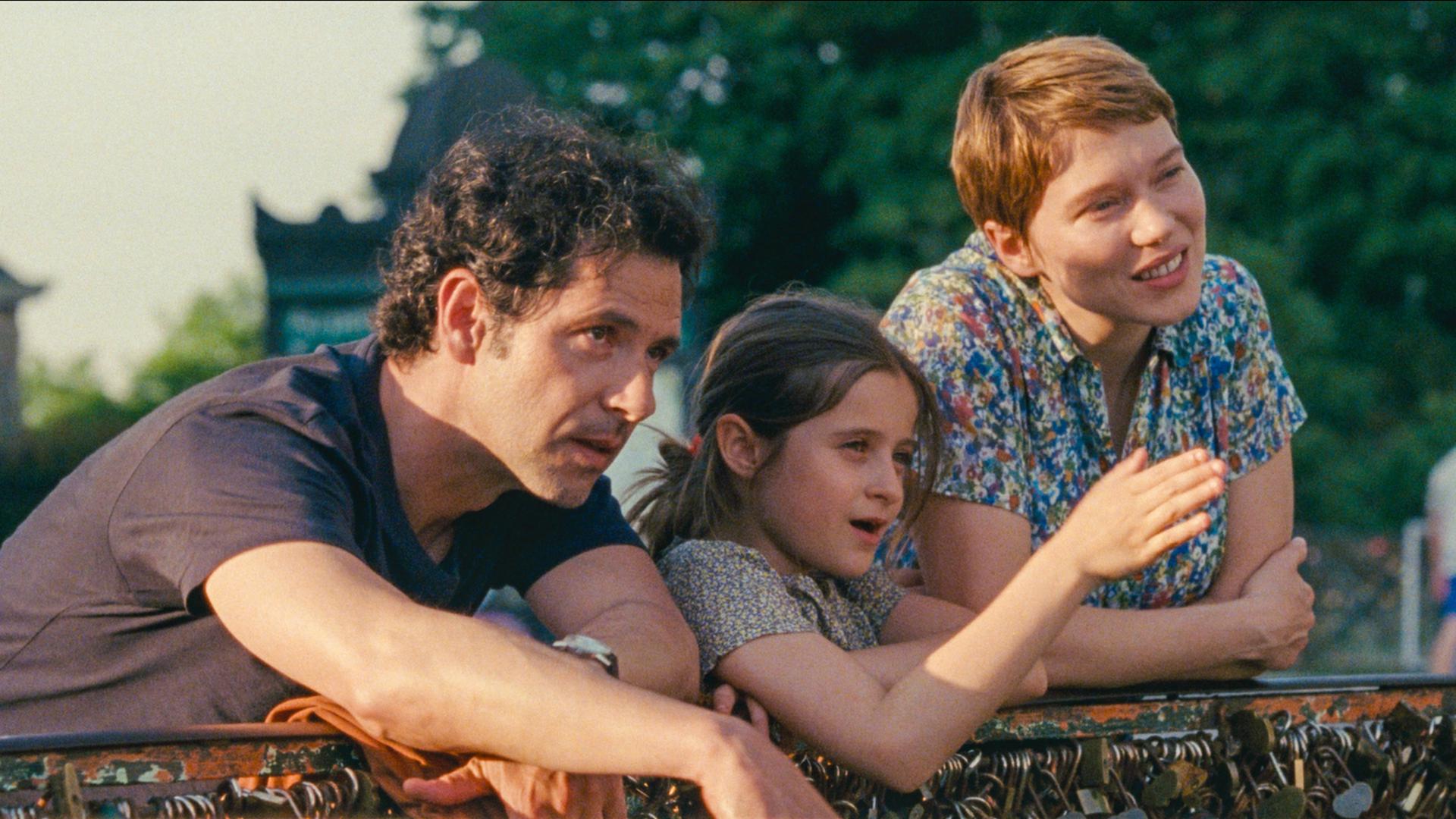

One year on from Bergman Island, her only title yet to have competed for the Palme d’Or, Hansen-Løve returned to Cannes this week in the more low-key surroundings of Directors’ Fortnight––it is indeed a more low-key film, and frankly a better one for it. It stars Léa Seydoux, perhaps the most famous French actress of her generation, though she’s rarely looked more normal: costumed here with short hair and casual dresses, she almost just about looks like someone you might actually know. Seydoux plays Sandra, a widowed mother stuck between caring for her ailing father, Georg (Pascal Gregory, delicate and heartbreaking), and her eight-year-old girl. She also begins an affair with an old friend, Clément (Melvil Poupaud), who only occasionally shows an interest in leaving his partner.

Working again from raw personal experiences (the director’s father suffered a similar degenerative disease, passing a few years ago), Hansen-Løve’s film suggests a refreshing angle on a devastating topic that has recently been in vogue (The Father, Gaspar Noé’s Vortex, and even back to Haneke’s Amour—why so often Paris?) One Fine Morning is just as concerned with showing the struggle to find Georg an appropriate care home, and is the gentler beast for it. We are never forced to witness the worst indignities of his affliction; simply seeing him wander around bewildered, shuttled from one public home to the next, gradually losing the ability to recognize his own children, proves more than sufficient to worry the tear-ducts.

Hansen-Løve peppers the cast with other performances to enjoy: Nicole Garcia has a pleasing cameo as Sandra’s mother, and Poupaud is enjoyably scuzzy as her burgeoning love interest, though I wasn’t fully convinced of their chemistry. One Fine Morning is ultimately Seydoux’s film and Seydoux’s alone. After a succession of larger-than-life roles, appearing beside James Bond twice and working for filmmakers as wildly varied as Wes Anderson, David Cronenberg, and Bruno Dumant, she has a character who is unmistakably human: unsure of herself, a lot of heartbreak and a little lost, and someone driven, for better and worse, by her own imperfect desires. Clément’s reappearance in her life also proves a sexual reawakening, and after a year without the carnal she’s ready to enjoy.

Hansen-Løve fleshes out her world in further satisfying ways. Sandra pays the bills working as an interpreter (which isn’t the metaphor you might expect it to be), a job that also allows One Fine Morning to visit locations far removed from the central drama. There is a scene at a government meeting and one at a World War II veterans’ memorial. If neither add very much to the plot, both offer the sense of a living, breathing world; when losing a loved one it’s easy to forget that life simply carries on.

It’s great seeing Hansen-Løve come full circle (again) in this way. After the misfires of Maya and Bergman Island, ambitious projects that never quite satisfied, One Fine Morning is like going back to a beloved novel. Shot in gorgeous natural light by Denis Lenoir (the cinematographer on all but one of her films since Eden), and backed by a soundtrack of typically esoteric needle drops, the director delivers her finest in years by doing what she’s always done best: a humanistic story of when to love and when to let go.

One Fine Morning premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released by Sony Pictures Classics.