While director Anthony Banua-Simon uses the revelation as a sort of “gotcha” moment to end his documentary Cane Fire, hearing Kauai-native Larry Rivera—an entertainer who performed at the Coco Palms before it was destroyed in a hurricane, who rubbed elbows with the likes of Elvis Presley and Bing Crosby—admit the only “Hawaiian legends” he knows are the ones his former boss Grace Guslander fabricated to awe tourists isn’t really a surprise. He and co-writer Michael Vass set the table for that truth too well throughout their deep dive into the island’s colonial legacy, separating allies from exploiters and ancestors from opportunists. That doesn’t make Rivera a villain. It simply shows the insidiousness of the systematic destruction and appropriation of Hawaiian culture and land.

We’re transported back to the origins of the Hawaii we know as the 50th state of America. Captain Cook arrives, white plantation owners follow, and soon you have the indigenous population being pushed off their land to make way for cheap labor transplants from China, Japan, Philippines, and more—who eventually learn to work the cane fields and pineapple canneries that inevitably earn their bosses millions. If anyone dared fight for a living wage, they were deported and replaced. It only made sense that big business (Banua-Simon focuses almost exclusively on a single corporation, Alexander & Baldwin) would invite Hollywood to film: a partnership could ensure anti-union propaganda made it into the result. Profiteers scratching profiteers’ backs en route to more exorbitant wealth.

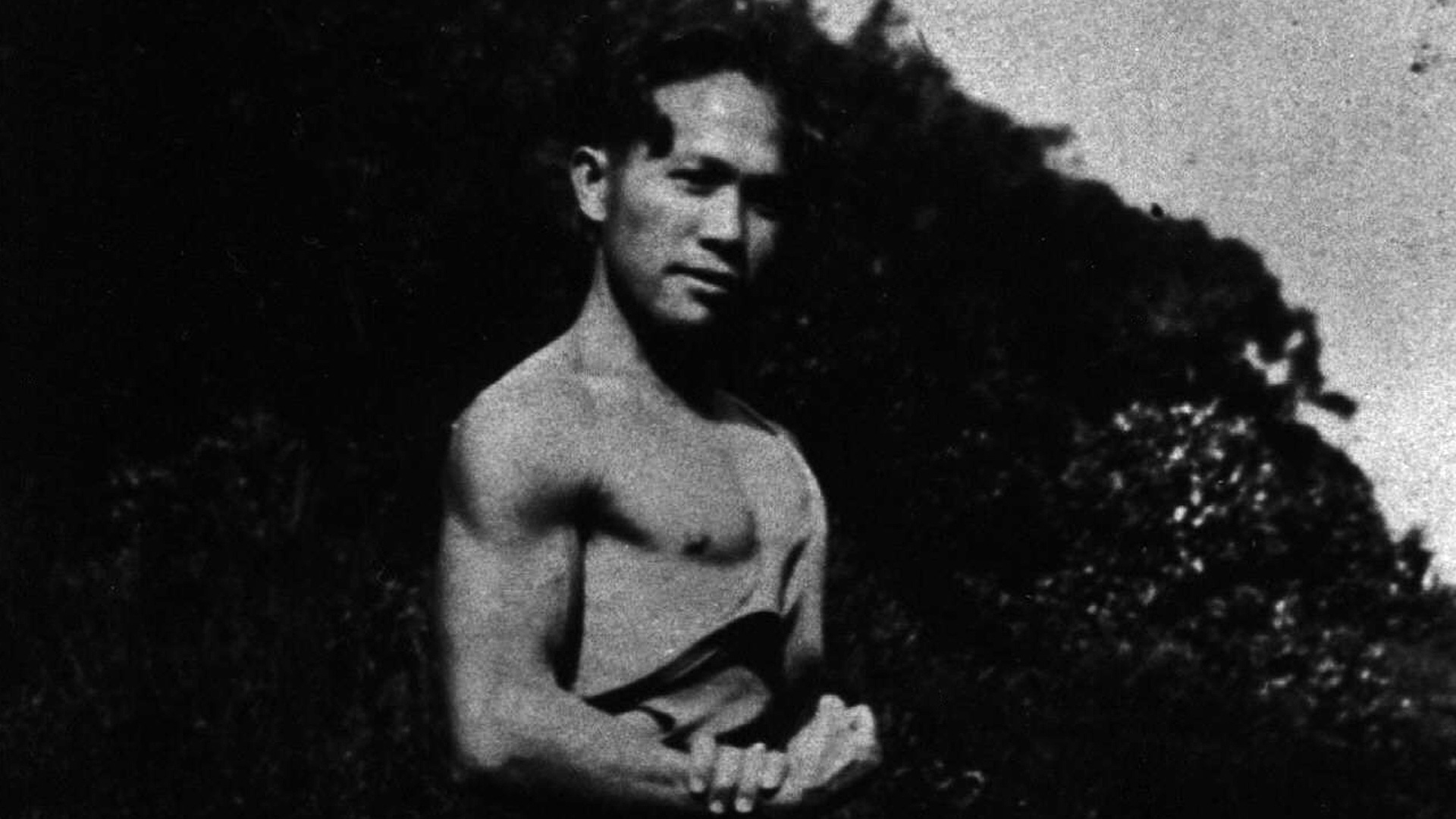

And Banua-Simon’s family experienced it all. His great-grandfather was a Filipino immigrant who ended up leaving after his work to unionize the cane plantations left him unemployed. His grandfather and great-uncle stayed and worked in both the agricultural and film industry—the former appearing as an extra in Lois Weber’s lost film White Heat, the latter serving as a driver for visiting directors. Now his aunt and cousins traverse the complex landscape of needing to exist within the systems that have destroyed their culture while also trying to stay true to them. That’s what happens when the capitalist machine takes over: you either join or die. Thankfully there are some who continue to fight anyway, knowing it’s a futile endeavor beyond exposing their enemies’ hypocrisy.

It’s through these familial ties that Cane Fire’s trajectory begins and through those strangers he meets along the way that it continues forward into the present. Banua-Simon narrates it himself, splicing interviews with his great-uncle Henry Bermoy and former union leader Alfred Castillo about the shift from sugar to tourism (and how everything the workers fought for and won in the fields was erased for those forced to enter the service industry regardless of both being owned by the same companies) together with clips from the many cinematic productions filtering those labor disputes and resulting poverty through an America First, anti-Communism lens. Everything that occurred did so at the behest of usurpers. And those struggling to survive became expendable annoyances upon their own land.

The whole possesses a pretty consistent narrative timeline, each new step building off the last with more invasive measures keeping colonialists’ descendants fat and happy. Banua-Simon’s main piece of scaffolding is the rising cost of real estate, how broken promises and weakening unions paved the way for the insane stat that over 50% of all residential housing on Kauai is owned by non-permanent residents using mansions as vacation homes and investments. He talks to the men and women who cannot afford homes of their own and mainland transplant Chad Deal, newly appointed Board of Realtors president, explaining how he “doesn’t make the rules” and is “preserving aloha” by selling stolen land to the rich elite. It’s familiar territory content-wise, but no less damning.

Where Banua-Simon gets inventive is his use of readily available commercials and YouTube videos to drive home the racist underpinnings of what has been happening since Hawaii was absorbed into the union. Archival film is great to discuss major events like the USA’s takeover (backed by the sugar plantations) and subsequent demolishing of Kauai’s kingdom and burial grounds (the aforementioned Como Palms was built upon the site, its own destruction at the hands of Mother Nature feeling like the byproduct of a karmic curse), but nothing portrays the gross indifference of consumer culture and “America Exceptionalism” like white women charging thousands of dollars for clay baths or white men intrusively filming strangers while mocking natives during vacation. Resort life is exposed as the damaging façade it is.

The vicious cycle sees no end, though. Banua-Simon’s cousins struggle to find work and stable housing. The current labor union head talks about conditions deteriorating to the point where a new worker revolt is unavoidable, even if she won’t be alive to witness it. And the Como Palms sees development to bring it back to life, despite native activists restoring the land to its former pre-theft glory. Like so much of America’s past, the image being sold is a lie meant to shield the public from a truth that no moral person could ever let be swept under the rug. Yet money walks, traveling between Kauai and Washington DC to solidify the one-party system that maintains the economic disparity billionaires on both sides of the aisle feast upon.

Cane Fire opens in limited release on May 20.