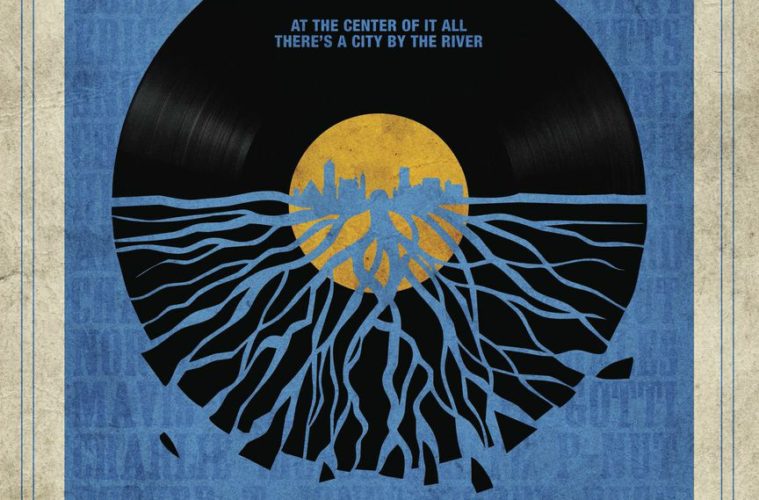

While it could have easily become a simple behind the scenes feature for an album of three generations of Memphis soul musicians coming together to recut some hits, Take Me to the River finds room to be more. Stewarded by director Martin Shore and composer Cody Dickinson, the simple act of getting these legends in the same room catalyzes the opportunity for stories to be told beyond lyrics. We hear them all individually outside the studio too in interviews explaining what it was like creating at a time of segregation, integration, civil rights, and the explosion of music with a unique flair bigger than race or gender that traveled the world. It’s history in song, remembrance, and the formation of new collaborations with up-and-comers and stars sadly no longer with us today.

The latter is what proves to be the documentary’s largest appeal because the sessions we see are some of their last. Someone makes mention early on about how many people were lost while the project was still in its infancy, so to be able to capture guys like Charles “Skip” Pitts, Bobby Blue Bland, and Hubert Sumlin in their element is an amazing coup. These aren’t the kind of people who simply show up, do their take, and go home either. No, there is palpable electricity involved as the old-timers embrace the rap interludes, the rappers declare their love for their idols, and Shore and Dickinson nearly pass out from glee watching the musicianship shore. When young and old talk about recording together again in the future it doesn’t seem like hollow words. The mutual respect is authentic.

A love letter to Memphis and its musical culture, Take Me to the River isn’t afraid to give us both good and bad in between recordings. Booker T. talks about his band with the M.G.’s as uniquely traversing the racial climate as an integrated ensemble. David Porter, William Bell, and others laugh about the origins of the hit “Hold On I’m Coming”. Luther Dickinson reminisces about he and Cody wanting to sing The Staples Singers‘ “Freedom Highway” and his mother calling Mavis and Yvonne for lyrics hearing them wonder why a couple of white kids wanted to sing a civil rights song. And Al Bell tells the story of Stax Records’ demise after Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder through economic racism and scapegoating. Honestly, though, just learning who worked with whom and who influenced who is a treat.

While you may stick around for the stories, the film’s true draw is the music. The combinations are inspired with Booker T. and Al Kapone laying down “Supposed to Be”; Otis Clay and Lil P-Nut doing “Tryin’ to Live My Life Without You”; Bobby Rush and Frayser Boy singing “Push and Pull”; Mavis Staples singing “Wish I Had Answered” with Luther Dickinson strumming her father “Pops'” riff by ear; and Bobby Blue Bland and Yo Gotti coming together for “Ain’t No Sunshine”. We’re given a glimpse inside Royal Studio, Zebra Ranch Studios, St. Blues Guitar Workshop, and Young Avenue Sound; see the rebuilt Stax’s current existence as a museum; and take a walk through the Memphis streets to catch monuments burnt into the history of Soul and America itself.

The list of artists involved span Ben Cauley to Snoop Dogg with actor Terrence Howard narrating and getting behind the mic for “Walk Away”. And all the while Shore ensures we see a little bit of the arrangement process, rehearsal, performance, and the aftermath when someone like Bobby Blue Bland can ask Lil P-Nut over to teach him it’s okay to sing from your throat when the diaphragm isn’t needed for long notes. This candor and willingness to help throughout allows “Skip” Pitts can tell a seventeen-year old guitarist and sixteen-year old drummer how genuinely good they are. There’s purity to the project in this way so that the final album and movie are merely documentation of the experience itself so we can at least get a taste of the once-in-a-lifetime convergence secondhand.

Constructing it around the songs themselves makes the film easy to follow too even if some moments seem out of context. It’s great to get the whole story of Otis Clay and P’Nut’s meeting without interruption, but it confuses when the latter is suddenly in the studio with Bobby Blue Bland five songs and maybe days later. I also get why Mavis Staples’ conversation is shown way before her actual song (which serves as the film’s final track), but you could have just ended with William Bell’s “I Forgot to be Your Lover” merging of legend, contemporary, and future. It’s a minor gripe for a film of this ilk because the multiple in-studio cameras and static interviews are really for archival purposes. Aesthetics aren’t meant to overshadow content—we’re here for the history and it arrives in spades.

Take Me to the River hits limited release on Friday, September 12th.