Besides the numerous raunchy one-liners spoken by the central quartet of aging stars for easy laughs, there’s one short passage from Fifty Shades of Grey that’s actually read onscreen. It comes courtesy of Candice Bergen’s Sharon and deals with the inexplicable decision to arouse Anastasia Steele with the “friction” of Christian Grey’s zipper. The line is a perfect barometer for whether you’re the target audience of E.L. James’ trilogy or Book Club, Bill Holderman and Erin Simms’ romantic comedy utilizing it as a catalyst for refueled libidos. You either giggle while continuing to read with baited breath and excitement, like Sharon, or squint in confusion before putting the book down forever. Being in the latter category, I’m obviously not this film’s target demographic. But I liked it anyway.

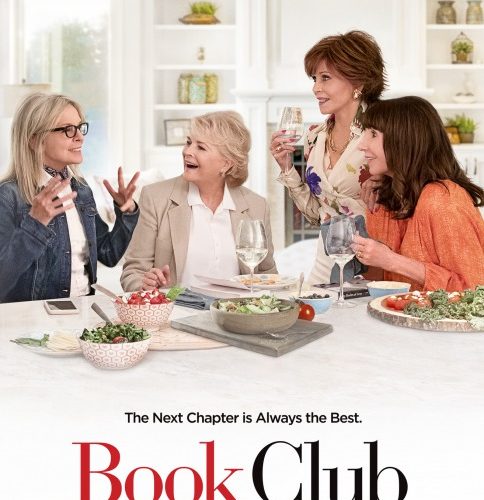

This isn’t a result I anticipated, considering the premise. Sharon’s a divorced and celibate federal judge; Diane’s (Diane Keaton) the recently widowed mother of two overbearing daughters (Alicia Silverstone’s Jill and Katie Aselton’s Adrianne); Carol’s (Mary Steenburgen) a “happily” married chef; and Vivian’s (Jane Fonda) a perpetually single sexpot of a wealthy hotelier. All are old friends who’ve met once a week for forty-plus years to discuss the latest novel they’ve collectively decided to read. Just as their lives are serendipitously upended courtesy of personal hang-ups and blasts from the past, Vivian chooses James’ fan-fiction sensation to get her BFFs in the mood to reclaim their sexualities. The assumption of lowest-common-denominator laughs is made true (and, boy, was the audience loving it), but only as a complement to its authentic heart.

It’s also unexpected because of the clichéd set-ups that had me dreading what was forthcoming — whether Sharon’s ex-husband (Ed Begley Jr.) shacking up with a woman (Mircea Monroe) their son’s age, Carol putting on her old waitress uniform to turn her husband’s (Craig T. Nelson) attention away from his double entendre of a motorcycle. Some stuff that Holderman (who also directed) and Simms have written is cringe-worthy and others tired sights gags, e.g. placing a very spry Keaton in senior-citizen hell amongst a collection of decrepit octogenarians left to die near the mall escalator. Add the obvious reactionary poses of out-of-touch “grandmothers” who constantly prove just how in-touch with the present they actually are and it’s hard to take a lot of what happens seriously.

Luckily, however, this is all a smokescreen for what’s really happened. Bergen failing to put on spanks and Steenburgen’s flower meter moving to “moist” while reading steamy prose are merely examples of broad humor meant to disarm so the true drama of real problems women their age face can play with honesty. It’s cute how Vivian falls in step with old beau Arthur’s (Don Johnson) flirtations and devastating to watch her insecurities hold her back. It’s charming to watch Andy Garcia’s Mitchell smoothly romance Diane and heartbreaking to witness as she rejects the joy of the moment because she feels like it selfishly means she’s emotionally abandoning her children. And those trajectories are cakewalks when compared to the debilitating sense of insufficiency and embarrassment Sharon and Carol combat.

These latter two are the ones who resonate most because they’re struggling to accept themselves and their circumstances rather than confronting a desire to adapt to change. In lesser hands, Steenburgen’s sexual appetite would be met in full by her husband’s blind testosterone and Bergen’s confidence post-getting back in the saddle with online dating (Richard Dreyfus and Wallace Shawn both send an electronic “wink”) would turn her into the persona Vivian can’t quite move past. But neither happens. Real life doesn’t make quick fixes that avoid tough conversations and self-reflection possible, so why should Book Club? It hints at them instead before pulling back to show the raw difficulties aging, retirement, death, and the generational divide present. Personal growth and self-care aren’t exclusively necessities for the young alone.

So while the studio is selling their product on a premise of laughing at the juxtaposition of “old” women saying spicy things, the filmmakers have taken care to move the whole beyond such one-dimensional constraints. This also means that Keaton, Fonda, Bergen, and Steenburgen aren’t allowing their immense talents go to waste. They are performing complex women surviving within the twenty-first century by rejecting the idea that life after sixty can’t be like it was at thirty. Fifty Shades of Grey may be here to make them horny, but that sensation isn’t a solution — it leads them towards confrontations they couldn’t engage in before. It reminds them that they’re allowed to have desires while also pushing them to face tough realities in their fight to earn satisfaction.

Book Club thus excels not in its boldness to be risqué, but its boldness to portray vulnerability. It’s about love’s risk versus reward and the acknowledgement that present happiness is worth the future’s potential pain. The number of contrived set-ups hinged upon new technology (e.g. dating apps) and bucking the Puritanical image society places upon its senior citizens to get to the good drama is many, and the journey can be arduously repetitive at times, but its actors make it worthwhile. Book Club will obviously delight the target audience, but its authenticity should also entertain their children and open eyes to the fact that their parents aren’t quite dead yet. This film may not be perfect, but it is commendably sincere.

Unfortunately, it’s also very white and very rich. Only a script dripping in privilege can let the following line be spoken sans irony: “I don’t want to change you. I love that you’re rich and independent.” One character constantly flies between California and Arizona like it’s no big deal, another presses pause on hundreds of working-class people’s days to take a call, and everyone has the means to pursue romance by not needing to worry about anything else. It’s the consummate Hollywood picture using affluence as a blank canvas wherein love isn’t presented in spite of financial security as much as a by-product of its freedom. So while Holderman and Simms do champion a demographic the industry neglects, they do it within a format that reinforces negligence.

Book Club opens wide on Friday, May 18.