For a way in, maybe we can detect that Zoology writer-director Ivan I. Tverdovsky is a fan of sad-boy rock star Morrissey, because the first ten to fifteen minutes of his not-exactly-successful film comes off like an adaptation of the lyrics of the seminal depression-jam “Everyday is Like Sunday”: both “Everyday is silent and grey” and “This is the coastal town that they forgot to close down.” The drab Russian life and home in question belongs to Natasha (Natalia Pavlenkova), a single, middle-aged zoo worker who still lives at home with her overbearing Catholic mother who, of course, seems to have instilled a deeply conservative, timid nature in her.

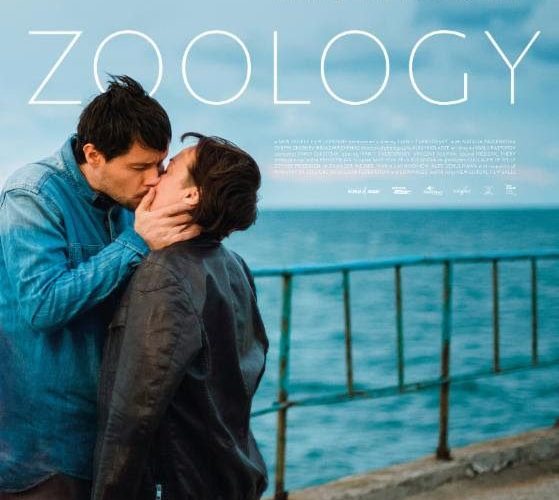

Though this is of a piece with the set-up of a fairy tale (portly, belligerent co-workers acting essentially as the wicked step-sisters), she all of a sudden finds a tail sprouting from her backside. Initially coming off as yet another curse instead of blessing, it leads her to the handsome younger doctor Petya (Dmitri Groshev), with whom a May/December romance blossoms. The relationship leads to her becoming far more outgoing and confident in her sexuality, be it a change in attire or letting it loose on the dance floor of a working-class bar — though only to clear it once her tail comes into view.

While able to be categorized under the magical-realist label, the film unfortunately heavily favors the latter word in that term, coming off as yet another festival title that seems to ape the Dardennes brothers’ signature camera-work, often hovering behind Natasha’s head as she moves through the various depressing locations. Which is not to say Zoology needs more quirk, per se, but the maintaining of this one register, despite Natasha’s shifts in attitude, is what ultimately seems to sink it. Be it the color palette remaining as muted as possible, though perhaps there’s props to be given to a film that rejects the corniest of opened-up point-of-view techniques — for example, there’s blissfully no Dolan/Iñárritu shifting aspect ratios here.

Still, one wishes the film was able, even within its modesty, to embrace its fantastical nature more, or at least give a Cronenberg-like precision to its ickier sexual implications. Case in point being a somewhat expected late reveal regarding Petya’s fetishes seen out-of-focus, giving almost too much sympathy to Natasha’s humiliation for the moment to truly register as being as gross as it actually is.

Even if Tverdovsky buries his film in naturalism, it doesn’t hide his weaker impulses for symbolism. Natasha at one point gets out of the office to visit the cages of her zoo, playing witness to a number of caged animals, in particular the harrowing sight of the hairless arm of a burn-victim chimp as we’re supposed to discern the echo of Natasha’s state as a fragile animal of sorts. But due to the narrow path, the audience — like her — only glances in pity, then quickly moves on.

Zoology is currently playing at the Toronto International Film Festival.