The thing I could never wrap my head around, religious-wise, is the idea of strict right and wrong. As a Catholic it’s somewhat easy as far as sin and repentance. You’re allowed to do a lot as long as you feel remorse and guilt enough to learn your lesson. But other religions are more stringent than Ten Commandments and more vehement in how each version of its worship follows its specific edicts. There’s no better place than the Middle East to see this in action—and I don’t mean ISIS versus Islam. I’m talking traditional versus modern. Both exist simultaneously in a country such as Egypt. You have the latter’s westernized clothing and attitudes alongside the former’s veil and prayer. To choose one is to forsake the other.

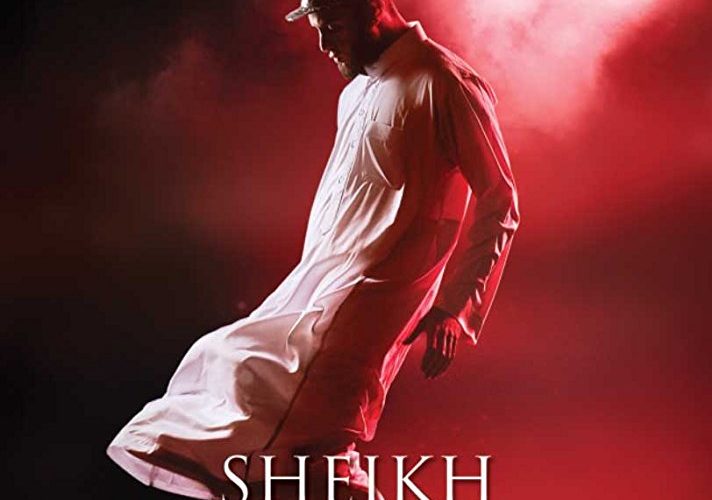

This revolt against duality is behind Amr Salama’s Sheikh Jackson and the young imam (Ahmad El-Fishawi’s Khaled) at its center. He’s just like any other devout follower of Muhammad and leader of Muslim faith upon introduction. He has short hair and a beard, wakes every morning to hold prayer, and wears a watch with two buttons (red and green) to keep an honor system tally of sins and blessings. He sleeps under his bed to prove piousness, spies on his daughter’s internet activities to catch any un-God-like behavior, and cannot look at a woman in public who isn’t covered from head-to-toe. He epitomizes his brand of Islam almost to stereotypical fashion and we thus assume it’s always been this way. The truth, however, reveals something else.

Salama and co-writer Omar Khaled ingeniously use the death of Michael Jackson as the catalyst to go back to Khaled’s adolescence. Memories of the King of Pop’s music show the great divide between Islam’s ranks and the separation of faith (Khaled’s uncle) and power (Khaled’s father as played by Maged El Kedwany) in the boy’s family. The popstar also provided a connection to young Khaled’s (Ahmed Malek plays him as a teen) mother. She admitted to liking his songs despite needing to keep it a secret from her “manly” husband quick to dismissively call Jackson a drag queen. The music became their little secret and Khaled’s obsession once she passed. He used it as an outlet to rebel against his father’s firm, conservative, but not quite saintly hand.

It’s obvious that Khaled changed his path and moved towards his uncle’s faith to become an imam. The question then becomes why Jackson’s death would impact him so heavily if he had put those days behind him. Anyone who has ever been faced with an ultimatum knows that one’s feelings towards the choice rejected never truly go away. Although Khaled forsook the “Devil’s” music and embraced the word of his Lord, Michael Jackson played an indelible role in his upbringing as well as the grieving process endured without the soft touch he needed from his father. The news therefore throws him off-balance as the emotions he buried long ago gradually rise to the surface. Do these thoughts diminish his faith? Do they reveal it to be a lie?

Khaled faces a crisis. His hope it stems from physical ailment only reveals a clean bill of health, the reality that his problems are psychological becoming too strong to ignore. It’s therefore these therapy sessions that serve as Salama’s movie’s backbone, the recollections of present and past spoken to a stranger helping him to understand why he can no longer cry. This matters because his congregation loved him for his passion. He opened himself to God in a way that made him break down during each prayer—something that suddenly stopped. The more we go back to witness his youth, the more we understand it’s not because Michael Jackson took his tears. Perhaps it’s the memories of a father who lived by a creed that men don’t cry.

So we watch the internal war for identity ignite within him. He becomes tested as a parent disappointed in his daughter’s love for Beyoncé like his father was in him. We see his refusal to unpack boxes he and his wife unloaded in their “temporary” home as a marker that perhaps this “home” isn’t the one he wants. And his work with his uncle to record a story to album and pass out flyers about the veil and faith becomes stalled when he remembers the women of his past (his mother and the teenager who shared his interests in school) were never beholden to either. Was his gravitation to Islam therefore pure or merely an escape from an oppressive father? Were his choices made for the right reasons?

Revelations are uncovered as well as an unavoidable strain of self-hate that had been warped into a shaky façade of newfound value. Nightmares about him being buried alive commence as well as fantasies wherein his life plays out like a montage of Michael Jackson music videos. This celebrity proves a totem of sorts to a crossroads in his life at a time when he wasn’t strong enough mentally or physically to make a choice for himself. There’s more to his father’s actions than mere “tough love” that pushes him away and those immoral trappings are inevitably found in the lifestyle choices of those who love western music and wardrobe much like him. Rather than reconcile these worlds, though, Khaled decides to erase one. This is the result.

But don’t think Salama is one to call lifestyle A right and lifestyle B wrong. This isn’t the goal of Sheikh Jackson. Instead he’s asking us to wonder when enough is enough and when wholesale submission to God becomes a detriment to the health of your soul. Khaled has grown into a fine man with a loving family—there’s no questioning this. It’s also the family that he wants. Where the uncertainty resides is who he is within it. Can he forget his past and continue moving forward? Or must he acknowledge it and therefore ease off on his zealotry to find a happy medium? He wants to preach to the young and help kids find Allah. But as he recalls his own struggles, he realizes full-scale censorship may only push them farther away.

Sheikh Jackson premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.