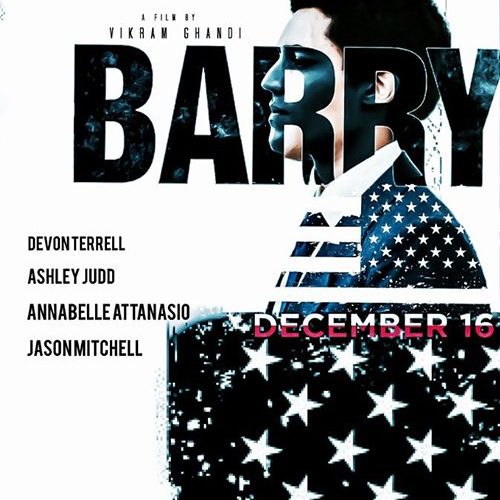

During his college days in New York, Barack Obama used to be called “Barry.” At that point in time he hadn’t fully embraced his African American roots yet, but was headed towards a journey of self-discovery that would change him forever. That is at least what writer-director Vikram Gandhi tries to show us in compelling drama Barry, which captures the tumultuous first few college days of the future U.S. president at Columbia University.

This is the second film about Obama to arrive this year after the Sundance hit Southside With You, which took place around 10 years later in Chicago. In Barry, Devon Terrell – an uncanny lookalike delivering a great performance — plays Obama with all the features and characteristics that we have come to know of the 44th U.S. president. He doesn’t just deliver a good impersonation of a 22-year-old Obama, but gets the humanity right as well. The performance is a fully sketched immersion that feels and looks like the real thing.

The swift wind of change that would invade Obama’s life happens within his first day on campus. He gets racially profiled by a police officer who thinks he is trespassing school property. The officer wants to hear nothing, not even a plea from Barry that he is in fact studying there and not an intruder.

One evening he decides to attend a party in Harlem with a crowd that seems to be foreign to him even though he shares the same skin color as them. The black side of his family, his distant Kenyan father whom he claims to have met only once, has been absent and uninvolved in his life. It his white mother, beautifully played by Ashley Judd, that has set Barry on the right path. Their relationship is carefully drawn out and reveals where the encoded free-thinking spirit of Barry’s might have come from.

As the film moves forward, Barry starts to feel more and more like he doesn’t belong, and what’s revealed seems almost too pertinent and relevant for the current social and racial climate in the United States. He starts dating a white girl, Anya Taylor-Joy (The Witch), a bright student that cares about him, but even that relationship becomes problematic. Barry is all too aware of how different his experience on and off campus is compared to hers. She doesn’t understand his frustration, but that seems to be his exact point. One cannot understand the black experience in America unless you step into their own shoes.

The racial tension in Adam Mansbach and Gandhi’s script is voyeuristic by simply, and smartly, showing us more than is explicitly said. Barry wants to be accepted, but he fears the path to acceptance will not come without major change in his country. He sees his brothers and sisters suffering daily, but is frustrated that he can’t do anything about it. A major decision for him would be to live outside of campus on West 109th, which would end up having him converse with black people on a daily basis, something he might not have previously done.

Whereas the aforementioned Southside With You was a calm, romantic watch, this is a serious and refined drama which has the feel of a political firecracker. Ending with his decision to not be called Barry anymore, but Barack instead, his transformation is complete and his investment into major political topics — such as race in America — is about to invade his persona and political life. In attempting to make the case that Obama’s racial experiences in 1981 at Columbia as what triggered and bustled him to the forefront of the political conversation for the years to come, Gandhi has succeeded.

Barry premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and will be released by Netflix on December 16.