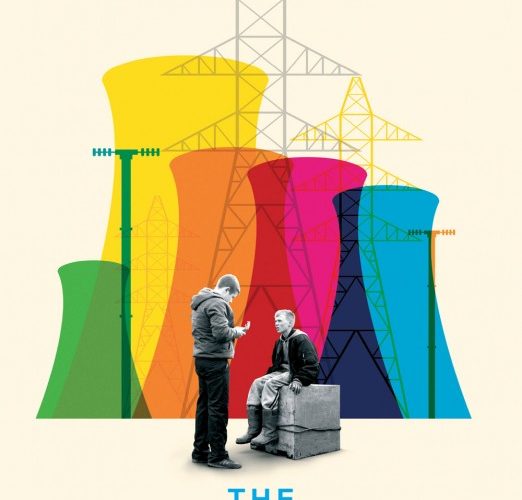

A contemporary fable thematically adapted from an Oscar Wilde short story and inspired by the world writer/director Clio Barnard entered while filming her documentary The Arbor in Bradford, Northern England, The Selfish Giant proves a stark drama wherein emotional growth blossoms through the aftermath of tragedy. It’s no surprise, however, considering the lengths poverty and a void of trusting role models drives young Arbor (Conner Chapman) and Swifty (Shaun Thomas) into a life far removed from the schoolboys horsing around and learning that they should be leading. With the former’s mother barely keeping he and his drug-dealing brother Martin (Elliott Tittensor) afloat and the latter’s gypsy parents selling their last couch in a room full of hungry kids to pay for electricity, a taste of steady income leads these thirteen-year olds onto their path towards destruction.

Barnard’s story is a simple one on its surface—two boys on society’s fringe seeking the adventure, danger, and wealth stealing metal for local scrapyard owner Kitten (Sean Gilder) can provide. Led by the fiercely loyal, hyperactive, and often out-of-control Arbor, this duo truly has only each other to count on. So when a schoolyard fight started by a couple bullies calling Swifty a pikey and finished by Arbor running out with adrenaline pumping through his less than formidable frame leaves the first suspended and the second expelled, they officially have nowhere else to go. But while Swifty’s mother holds onto hope and makes him attend school anyway to sit in the office and show his commitment, Arbor relishes his newfound freedom “working” and quickly recruits his best friend to join him like the bad influence he’s always been.

It’s an unfortunate reality of exploitation wherein these boys revel in the fact they can bring in money to help support their families as Kitten is afforded all the cheap child labor he could ever want to do his dirty work. He is the selfish giant of the title, a man assuaging his guilt by telling Arbor the boy’s first theft would be the last shipment of wire he’d accept while also teaching him the tools necessary to make the metal untraceable knowing the kid would never take “no” for an answer. It’s a master manipulation that hooks Arbor as soon as the cash hits his palm, one he follows suit by then lording his friendship over Swifty to exploit him in turn. And with little or no father figure showing interest, Kitten’s favor becomes just as integral a motivation for both.

This is where their disparate personalities come into play as Swifty’s want of praise and Arbor’s yearning for power puts them onto a collision course with destiny. A subplot concerning the horse racing affinity of Kitten’s gives Swifty’s more sensitive minded and compassionate soul the first leg up on Arbor he’s ever possessed. Whereas the latter’s drive to steal metal only makes him one more of a long line of replaceable thieves (a liability at that with his ADHD exacerbating his temper and greed to uncontrollable levels), his friend’s skill was one nobody else could offer. Kitten’s obvious appreciation for Swifty over Arbor therefore makes the boy even more volatile, escalating his greed beyond satiation until he’s stealing from his employer to resell to a competitor as the adult consequences of his situation unavoidably catch up.

Barnard bolsters this central friendship and subsequent unwitting rivalry with myriad background details to flesh out their world and expose how dire circumstances are. There’s Arbor’s brother selling his Ritalin pills to leave the youngster unable to cope with his affliction while leading himself towards jail or death when the crime can no longer support the habit; the boys’ mother Shelly (Rebecca Manley) struggling as a single mom powerless to help their rapid descent into chaos; the ridicule and bigoted remarks launched towards Swifty and his parents (Steve Evets and Siobhan Finneran) from kids and adults alike; the dangers inherent with stealing metal in a derelict industrial town riddled with live wires; and the unavoidable disintegration of youth when kids are forced to take on much more than they can or should ever handle.

Comparisons to Oliver Twist in the press notes are spot-on as we watch Kitten use these boys for financial gain, stringing them along with the promise of survival as their dark and unyielding way of life finds itself all too willing to pretend they’re involved in a symbiotic relationship with only the police as adversaries. They don’t yet see how much worse their fates will be at their own hands once hubris exposes mortality and selfish desires cloud judgments until the want for control leaves them desperately alone. Isolation is Arbor’s biggest fear—something he’s never had to face with Swifty by his side as each other’s only friend. But as Swifty finds purpose with Kitten and Arbor’s greed has him teetering on the edge of a lifestyle he’s simply too young to understand, you must wonder who the real villain is.

Is it Kitten’s guilt-less utilization of under-age urchins, Arbor’s hunger for power to get back at those who’ve dismissed him his entire life, or the environment failing them until these children can no longer avoid adult responsibilities from falling on their shoulders? Barnard gives each character a hidden conscience put aside for a survivor’s mentality before the consequences of such thinking make it impossible to pretend morality isn’t paramount. Thomas’ Swifty’s innocence exposes this complexity in both Gilder’s Kitten and Chapman’s Arbor as the light of optimism they’d both do anything to keep for their own personal salvations. Pushing and pulling him to his breaking point, Swifty never wavers in his obedience or love. Instead they only end up breaking themselves—the tragic realization neither could return the favor becoming all they have left by the end.

The Selfish Giant hits VOD and limited release on Friday, December 20th.