The Confirmation opens with a child and his mother waiting outside a church. As the first lines of dialogue were spoken, I felt a sudden pang of shock, thinking I had unwittingly sat down for one of the numerous heavy-handed faith-based features crowding multiplexes. Thankfully, as it continued, the film revealed itself to instead be a rather smart comedy in which faith is a subject sometimes pondered by its characters. Seen through the eyes of its young protagonist, there is so much power in those big unanswerable questions of faith. The boy’s middle-class parents do not see eye-to-eye on the matter of religion, rarely agreeing on any subject since their divorce.

The first directorial effort from Bob Nelson, who also pens the screenplay, is another father-son tale following his Nebraska — this one a more slight, albeit heartfelt dramedy, set long after the parents’ break-up. It is not a film that provokes or challenges its audience, serving up quirky characters in a warmly inviting and sometimes silly fashion. A far cry from Payne’s film, but rather watchable and charming in its harmlessness.

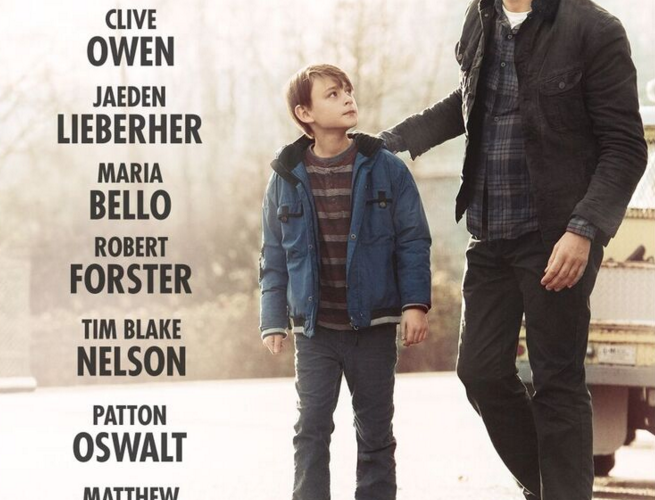

Telling a sunny, uplifting story of an 8-year-old boy helping his father, Walt (Clive Owen), recover a stolen toolbox for a new job, the film is also occasionally laugh-out-loud funny despite an innocuously safe approach. The narrative is crisp enough to intrigue, thanks to Nelson’s earnest, down-to-earth writing. Like Nebraska, The Confirmation is set in blue-collar America, where money is on everyone’s mind simply because of how little they have. Walt’s lingering unemployment hangs over his head like a cloud, an embarrassment that he’s desperate to make right. Brief interactions with his ex-wife, Bonnie (Maria Bello), indicate their relationship was likely destroyed by the husband’s financial irresponsibility.

Owen is a performer who can easily command authority, a quality that, when subverted here, imbues his turn as a poor man also recovering from alcoholism with a sense of empathy. One doesn’t expect the film to take us to the places it heads, feeling more sympathy for Walt with each passing hardship. It’s certainly terrible to encounter disappointment, but it must feel even worse to have these embarrassments witnessed by your impressionable children.

One of the film’s strengths lies in the performance of its young star, Jaeden Lieberher, who carries a vast majority of the screen-time. Lieberher, who will be seen again shortly in Jeff Nichols’ Midnight Special, acquits himself rather well, playing off Owen’s unstable parent with deadpan sincerity. The boy wisely delivers a naturalistic performance that helps the film’s humor resonate. No joke feels broadly sketched or forced, even as we watch a small child verbally outwit his adult counterparts.

The comedic digressions are the most successful element, far more than the nearly non-existent emotional payoff. The biggest laughs stem from these flawed, misguided protagonists, their richly defined authenticity evident in all of their hang-ups and contradictions. Between the father and son, Nelson satisfactorily captures that enlightening shift in perception where you finally begin to see your parents as imperfect people, just like yourself or anyone else. The Confirmation can evoke memories of Miguel Arteta’s The Good Girl or Kenneth Lonergan’s You Can Count On Me as we follow these flawed people around in their attempts to do the right thing, often misguidedly. While it’s not nearly as deep or cutting as those pictures, the tone lands in that ballpark, addressing “the common man” without mawkishness or condescension.

Each passing scene invites another capable performance into the party, including turns from Patton Oswalt, Tim Blake Nelson, Matthew Modine, Robert Forster, and Stephen Tobolowsky. Terry Stacy‘s cinematography is understated and often lovely. Fitting with its characters, Nelson attempts no fancy gestures with the camera, allowing performances to remain the focal point. There are occasional marks of a first-time director when the visualization feels less cinematic than functionary, conveying the story and absolutely nothing else.

The Confirmation slightly loses its balance in the end, its resolution failing to inspire an intended emotional pop. When the stakes are raised, its characters begin to move like puppets, cued by requirements of the plot — a crucial misstep. The too-hurried and convenient final developments leave characters behaving in ways that are, if not necessarily unexpected, perhaps too overly saccharine. In particular, Bonnie makes a decision late in the film that stands out as a possibly unearned, yet understandable narrative necessity. Yet the bookended diversion involving a confessional is a payoff that, though predictable, lands with graceful wit.

Nelson’s screenwriting voice is unpretentious, approaching earnestly grounded characters with a deliberate lack of sentimentality. If Horton Foote and Elaine May had a baby, they may very well produce something like this. His writing can be funny and touching, inspiring laughs of sympathy and identification. We’ve known people like Walt and Bonnie, and we can understand how they once ended up together and, sadly, apart. But they’ve still managed to raise a child who is honest, funny, and precocious, a curiously innocent mind still looking at the world with wide eyes. Like the child, The Confirmation doesn’t have a cynical turn in its repertoire.

The Confirmation arrives in limited release and on VOD on Friday, March 18.