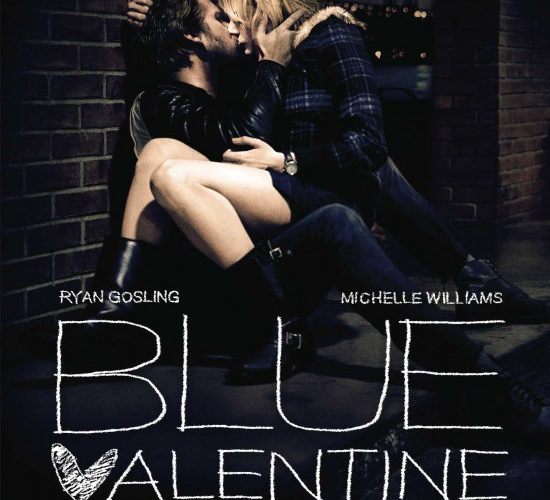

While much of the attention this drama has drawn has been for its unwarranted then overturned NC-17 rating, Blue Valentine is much more than the sum of its supposedly salacious sex scenes. At its core, Derek Cianfrance’s long-developed indie is a heartbreaking portrait of the end of love. This earnest and raw drama, which stars Michelle Williams and Ryan Gosling, trippingly reveals the beginning and end of a once glorious love, balancing scenes of film-shot rosey-eyed romance with cold and digitally-captured sequences of a rotting marriage.

Cianfrance has worked predominantly in documentary, and it shows as he ardently strives to present this bittersweet story in a frank and ungarnished manner that rejects the typical Hollywood tropes of glossy stars and zipperless sex scenes. Instead, Cianfrance cast a number of non-actors in supporting roles and encouraged his actors to improv, which adds to the sense of authenticity. While both the film’s stars are compelling, Gosling really shines with this new freedom, eliciting easy laughs with his winning charm as the blue-collared romantic, Dean. Williams has the heavy-lifting in this piece, playing an ambitious med student named Cindy, whose life is sidetracked when she discovers she’s pregnant. The two play brilliantly against each other, re-affirming their reputations as solid and compelling performers. With such sizzling onscreen chemistry, its little wonder gossip mags are speculating the two are a real-life couple.

While the scenes of young love are well-structured and glow with optimism and moxie, the present-day sequences are strained and tend to linger longer than needed. In their heyday, the pair is young and beautiful, full of passion and a joy to watch. The scene teased in the trailer, where Gosling plays a ukulele and Williams tap-dances, unfolds with such simple grace that it’s haunting—especially when contrasted with the vitriol the pair spouts at each other in latter sequences. The film flashes forward about seven years or so; Dean is balding and beer-drinking at breakfast, and Cindy’s infuriated by how her life’s played out. Dean tries to reconnect with her on a night out at a cheesy theme hotel. Hopeless romantic/optimist that he is, he chooses “The Future Room,” which turns out to look more like an 8-year old boy’s dream bedroom than a sexual fantasy getaway.

It’s these scenes, where Dean tries to engage his wife in sexual healing, that got the MPAA lathered up and are the most harrowing to watch. American films rarely capture this kind of raw vulnerability and emotional danger. Sadly, Cianfrance overplays his hand. While he carefully uses small visual cues and brief lines of dialogue to paint the picture of a fractured relationship, the sophomore narrative director doesn’t seem to trust himself in a narrative format, as the resolution plays out much longer than needed. After this failed tryst, the audience knows their marriage is over. But Cianfrance plods through an awkward sequence at Cindy’s workplace followed by a drawn-out heart to heart in her father’s house. So much pathos deadens the impact as the blows go on, leaving one punch drunk from overwrought melodrama.

All in all, Blue Valentine is a bold American drama that handles relationships and sex with a mature and careful hand. Sadly, like his male protagonist, Cianfrance doesn’t know how/when to let go. Still, it’s a stupendous film, well worth the price of admission – though I wouldn’t recommend it for a date night.

Blue Valentine opens in limited release December 29th, 2010.