While playing a game of “mafia,” Babak (Shahab Hosseini) and Neda (Niousha Noor) are tasked with figuring out who amongst them (it’s an evening with friends rounded out by two more couples) are gangsters and who are citizens. The idea is to therefore lie if you’re the former. Pretend you’re innocent and point your finger elsewhere in hopes that the majority of players choose to “kill” the wrong person. A poker face is king and in this case salvation for those searching for one last victory before kababs are grilled and conversations move to more serious matters. That’s not to say this sort of deceit doesn’t also bleed into those matters too. Secrets are inevitable. They sometimes prove necessary. The question becomes whether you can stomach the guilt.

As a sudden toothache reveals, Babak’s constitution for keeping his shame at bay might not be as strong as he thought. Or perhaps changing circumstances have changed him. Because despite his living in Los Angeles for five years, Neda only just arrived from Iran less than one year prior. That’s a lot of time apart. Anything could have happened. To reunite now with a newborn baby in their arms may seem like a good way to erase the slate and start again, but these things are much more complex in practice. Not only is it a matter of blindly forgiving or actively ignoring the other’s actions, it’s also about accepting your own. Can you look into the mirror with a clean conscience? Can you truly move forward?

Director Kourosh Ahari and co-writer Milad Jarmooz know the answers to these questions aren’t black or white. So they give the couple’s uncertainty and anxiety form by way of the supernatural. Maybe it’s a literal curse bestowed upon them when they decide to get two halves of a unique design’s whole tattooed onto their forearms without knowing what it means. Or perhaps that superficial bond has merely allowed the tumultuous emotions swirling within them to rise because they know it’s nothing more than a mask. The GPS gets wonky either way as Neda worries that Babak is too drunk to drive. They ultimately stop at a mysterious hotel to calm down and refocus after some sleep … if The Night is willing to let morning arrival at all.

It’s an intriguing premise in that its familiarity is tempered by a potential to deliver something fresh if only because its leads aren’t your usual middle class, white Christians worrying about the Devil. Babak and Neda speak Farsi and exist with a certain set of patriarchal rules he’s quick to wield involuntarily while she does everything she can to push back. The first fact makes it so characters like Elester Latham’s “displaced man” randomly speaking their language lends an almost other-worldly feel as though what we’re seeing is happening in their heads. The second fact makes room for a welcome bit of subversion (Babak has obviously done something culture can’t and shouldn’t excuse) that sadly never comes. Its inherent misogyny instead grows to risk derailing everything.

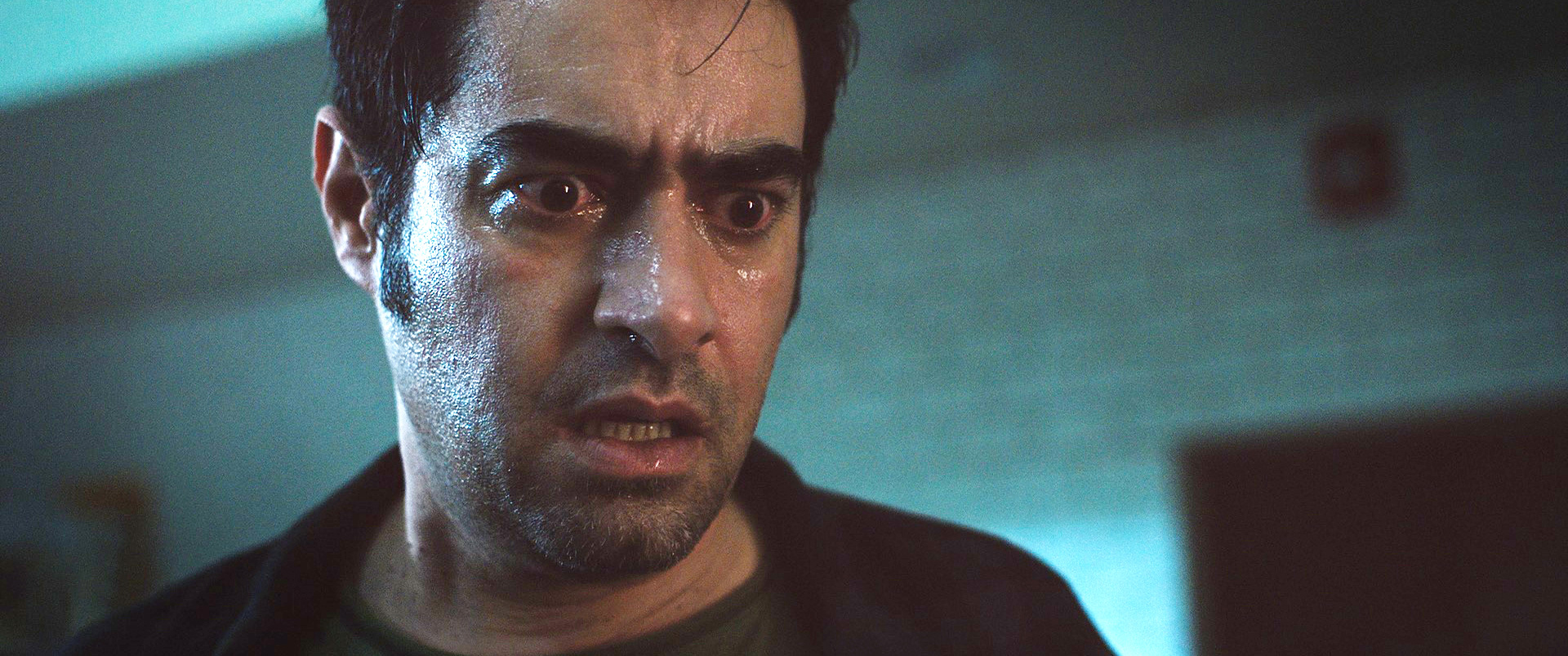

The reason is simple: this is Babak’s movie. He’s who we meet at the start while he’s dealing with the pain of his tooth in the bathroom. He’s who we follow inside the hotel—mostly staying with him as he wanders the darkened floorplan amongst ghosts, hallucinations, and harbingers of death (George Maguire’s concierge is contrite when speaking about his closeness to tragedies, but no less excited to revel in the brutality). As such, it’s Babak who we’re told has a dark secret concerning an unknown woman he’s too afraid to mention with any real detail. Until he reckons with the truth of who she is and what he’s done (presumedly while Neda was in Iran), escape is impossible. The doorways out of this nightmare will remain locked.

That a young boy also appears isn’t a problem until discovering his main target is Neba. But she neither receives the time nor context Babak does to earn such scrutiny—especially considering a conclusion that looks to all but erase her experiences anyway. So when the plot asks us to believe that she also has a secret she must divulge before they have any hope of going home, it can’t help proving an impossible order to fill. Up to that point Neba has been nothing but a check on Babak’s chauvinism. She’s been the mirror that shows he’s unraveling and perhaps too volatile to care about. Ahari and Jarmooz seem to be drawing her as his salvation only to saddle her with what they think is comparable guilt.

It’s not, though. Neba’s guilt is born from a situation Babak created and yet the film forces her to endure more pain than him as a result. Add a moral superiority to the tone of this secret and it’s easy to check out completely despite the effective atmospheric dread and tense horror leading towards it. There’s probably some wiggle room insofar as whether her secret is even real (perhaps Babak has created it as a way to lessen the burden of his own guilt about events that are at best sinful and at worst criminal considering the full picture is intentionally obscured), but only if you let Ahari get away with a rug pull that’s too abrupt to not feel like a course-correction rather than a purposeful evolution.

People won’t be happy with this secret. Nor should they. Ahari might be infusing his script with this hot-button issue because it’s a difficult conversation for couples to have openly, but he doesn’t include that conversation. He instead equates its gray area with an objectively horrible act in a way that makes it seem there shouldn’t be a conversation at all. Does it ruin his goals? No. As a journey inward into the roiling waves of memory and regret, Ahari fulfills his promise with an unapologetic air of penance and disgrace. That its success happens despite his exploitation of Neda as a character and woman doesn’t, however, negate that egregious misstep. And the latter being highly triggering unfortunately renders any blind recommendation of the former a reckless proposition.

The Night opens in limited release, VOD, and Digital HD on January 29.