What does it require to take the ‘unfilmable’ and transfer it successfully to screen?

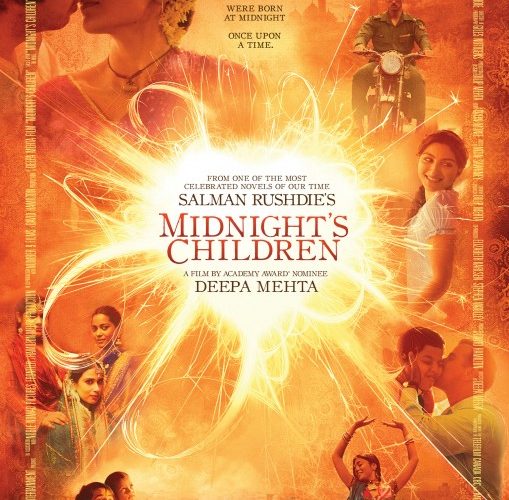

This was the quandary director Deepa Mehta and author Salman Rushdie faced when attempting to adapt Rushdie’s own esteemed classic, Midnight’s Children for the cinema. Their resulting response is not especially heartening, as it implies that the answer is two-fold, beginning with ‘compromise’ and working forward to ‘more than you are likely willing to give’. The Midnight’s Children that arrives in theaters is in no way a disaster and it is as filled with as many lovely and heartfelt moments as Rushdie and Mehta could find time for. However, as the onscreen emissary of the author’s Booker Prize-winning best work it lacks conviction and grace.

In the end, how could it have been otherwise? For those familiar with Children in its literary form, the pitfalls of streamlining this rich stew of magical realism, Dickensian melodrama, and fifty-plus years of tumultuous Indian history are obvious. The true difficulty is that Rushdie relied upon his work’s epic structure for emotional and intellectual heft, but delivered the poetry and meaning through the smaller, isolated details of his characters and their personal legacies. There’s simply not enough time on screen for both of those—apparently not even in a 146 minute film—and the balance would be obviously disrupted if one of the two was truncated.

Mehta, unsure of which side to unmoor has reduced both aspects and replaced the resulting emptiness with the typical allure of art-house India, drenching everything in scenery, color and music. These elements enhanced and provoked her character driven early films like Fire, Earth and Water but here they become a constricting stage for Rushdie’s mammoth tale, cramping the foreground with simply too much theatrical baggage. Rushdie himself has co-written the screenplay, and even narrates the film; eliminating his protagonist’s oration from the book and in the process unwittingly undermining the notion that Midnight’s Children could stand on its own without the associations of its infamous creator.

Only his second novel out of the gate, Children catapulted Rushdie to the ranks of literary auteur as certainly as his later work, the divisive Satanic Verses, made him a political pariah. The book and the film follow the life and trajectory of Saleem Sanai, son of a destitute street musician, who is born “at the glorious hour of India’s independence” from British rule. Shortly after his arrival, a literal-minded nurse who practically interprets the mandate ‘let the rich become poor, and the poor rich’ swaps Saleem with another child. The other boy is Shiva, who now grows to a man in the slums of Bombay (mostly off-screen) while Saleem arrives at adulthood through a more privileged upbringing in the care of a wealthy Muslim family.

Children intertwines the fates of both men, who identity with families and parentage not biologically theirs, pulling back to examine them within the context of India’s own national identity crisis. Saleem and Shiva merge into the grander tapestry of the tale; the story begins a generation before their birth and is not resolved by their eventual meeting. Mehta elegantly sketches their emotional journey and deftly contrasts it against war, revolution, and social change. Mehta’s actors carry the film, particularly Darsheel Safary and Satya Bhabha as the child and adult versions of Saleem respectively, and Siddharth, who evokes an imposing and multi-faceted figure in Shiva, Saleem’s mirror rival. In the best moments, Mehta marries the personal to the national with emotional shorthand that allows us to connect briefly with the story’s inner heart.

What works less well on screen is the fantastical conceit, playing like a muted take on Alan Moore’s Watchmen. It turns out that Saleem is actually psychically connected to 581 other children—including Shiva—who were also born on that day of India’s revival, each with their own special powers that may determine the fate of the India at large. The film visualizes their telepathic bond as illuminated specters that appear to Saleem in his room at night like a ghostly slumber party. As Children moves forward to the 1970’s, a secret history is played out as Shiva’s pursuit of these gifted stewards who threaten him becomes the real motive behind Indira Gandhi’s infamous military rule and the destruction of the slums of Delhi. As compelling as this science fiction bent is, it never really coalesces with the other aspects of Midnight’s Children and creates a sense of on-screen schizophrenia.

That patchwork sensibility is what ultimately prevents Midnight’s Children from being anything other than a handsome, static adaptation. Newcomers are likely to be even less satisfied than those familiar are because they will observe the movie as a series of vignettes lacking the essential roots put down in the novel. The film opens with a country doctor forced to view a village girl through a hole in a sheet, examining the afflicted portion but no more; he ultimately falls in love with her, but has done so one body part at a time. Audiences will experience something similar, only to be jilted at the end when the sheet itself never lifts to reveal the sum.

Midnight’s Children is now in limited release.