On paper, Henry’s Crime, especially with the strong talent involved, could have been a fun and clever heist film. In execution, it’s neither of those things. There’s a lifelessness to the film that adds up to a dull, half-baked result.

The plot is fairly simple and filled with promise: Henry (Keanu Reeves) is a nice man who’s convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. Henry was asked on the whim to drive some of his buddies to a baseball game, during November, and he foolishly agreed to his shady friend’s (Fisher Stevens) request. That request is to really rob a bank, and he’s the unintentional getaway driver.

After a couple of years of a brushed by time in prison, because he was just too nice to rat on his crappy friends, he ended up meeting a newer and better friend in the big house: Max (James Caan), a father figure of sorts. Henry serves his time, but once he’s out, he’s pathless. That is, until he decides to finally do the crime he was convicted for. Henry convinces Max to finally go for parole and also, wisely so, recruits one of his unreliable friends to help him out.

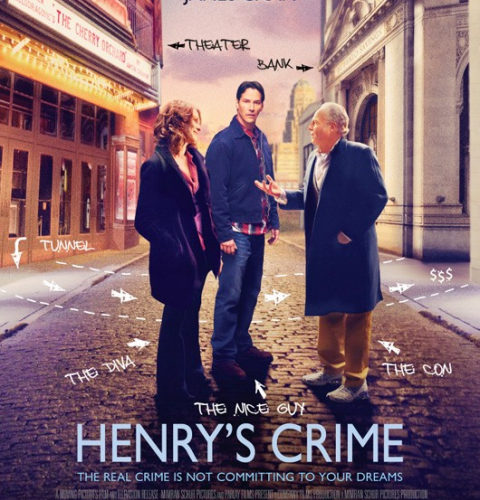

Right before this scheme starts, he meets Julie (Vera Farmiga). A charmingly cold, sarcastic, and cynical woman that couldn’t be more different than Henry. Farmiga usually has a sense of warmness to her, but here, not so much. Julie’s vulnerability comes from her cynicism, and you easily understand why Henry is interested.

Unfortunately, most of these basic string of events are underwritten. Everything always comes off without a pulse, except when Caan or Farmiga are on the screen. Reeves, on the other hand, has a script that consistently undermines him. Henry is a nice, shy guy, and that’s about it. Right from the beginning Reeves has to fight to make him appealing. Throughout the film Henry is making questionable decisions out of his passiveness, which is more annoying than endearing.

I consider myself a fan of Reeves’ work, not an apologist, and here he does what he can. The whole cast tries so vigorously to make Henry’s Crime play well, but by the end, you come to learn that’s near impossible.