Philippe Garrel’s modus operandi since 2013’s Jealousy has been unfussy, melancholic, black-and-white tales of Parisian men in the throes of romance, typically under 75 minutes. His latest, The Salt of Tears, which played in competition at the Berlin Film Festival, stretches to 100 minutes, but retains much of the lo-fi monochrome aesthetic, here centering on a cocky, shaggily attractive 20-something whose predilection for spurning women won’t win admirers from the MeToo generation.

But The Salt of Tears, with its title that sounds like a philosophical tract by Sartre, is a distant, ruminative film that refrains from wallowing in snide judgments of its characters. Perhaps to its fault, it’s a sober, adult, sincere film that seeks to consider some truth of the fallacy present in all human relationships.

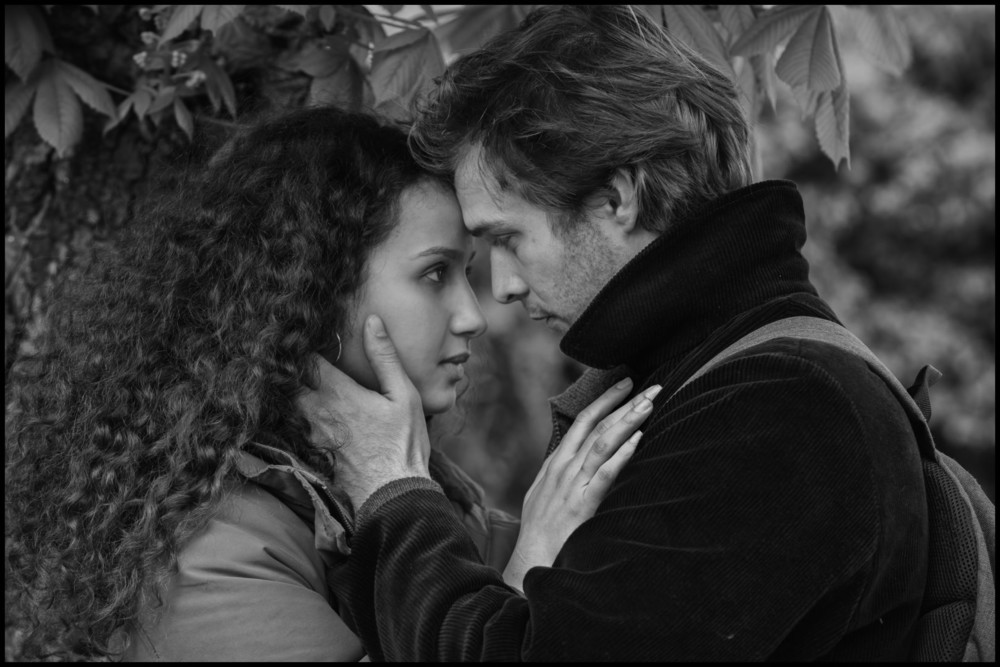

The story follows trainee carpenter Luc (a pretty but, ahem, wooden Logann Antuofermo) through a trio of romantic misadventures, as he moves from the French countryside for something akin to a sentimental Parisian education. The first is Djemila (Oulaya Amamra), whom he matches with while scouting each other at a city bus stop (Tinder makes no appearance here). Luc’s urge to jump straight into bed with her is our first indication that his intentions aren’t entirely honorable. Amamra, so luminous in 2016’s Divines, is given far little to do in a small role.

Luc soon returns to the provinces, where he rekindles a teenage romance with the bubbly Geneviève (Louise Chevillotte, last seen in Synonyms), but after a few summer months of relative bliss–at least for her–she looks for greater commitment. It’s too much for Luc, who scurries back to Paris to complete his training. Luc then hitches with Betsy (Souheila Yacoub), who gives Luc a taste of his own medicine as someone for whom monogamy is a challenge rather than the norm. Yacoub’s performance is the most cryptic of the women, and better for it.

Some of the film’s early scenes made my teeth grind, partly because Garrel puts us in the shoes of the film’s caddish protagonist–Antuofermo’s rather limp performance suggests there’s no great depth to his character. But Garrel slightly wrongfoots the viewer here, in that there’s a tragedy to Luc’s character arc that takes a while to flesh out. His hollowness isn’t merely a script lacking in psychological depth (Garrel co-writes with Jean-Claude Carriere and Arlette Langmann)–it’s his defining character trait.

But the film doesn’t bring much to life to its female characters either, or give them much in the way of agency in the story. Each reveals itself as a cipher of Luc’s sexual anatomy–submissive, provocative, dominant–which lessens their impact as individuals with distinctive voices. Garrel is also unforgivably liberal in showing female nudity while keeping his male protagonist protectively clothed.

In the background throughout is Luc’s father (André Wilms), also a carpenter but of an older generation, who puts all his hopes into his son. It’s through this familial bond, and Wilms’s touching performance–the best in the movie–that reveals something of the fragile nature of Luc’s character. The only person Luc truly loves in the film is his father, and Luc knows that for all the mistakes he makes, there will always be someone to be there for him. That is, until he’s gone.

Garrel’s regular DP Renato Berta returns, with black-and-white photography that both enhances a melancholic romantic ambiance, while also making the proceedings somehow more down to earth. Although for all its pastiche Nouvelle Vague aesthetic, it has some important updates–not least the racial diversity of its cast. But I found myself striving for something new are revealing in the film, which marks something of a come-down from Garrel’s moving previous film, Lover for a Day.

If anything, what Garrel’s film lacks in emotional connection it gains in reserved reflection. It’s a study in male chauvinism, and yet these characters–both men and women–are adults, in adult relationships, whose responsibility is theirs alone. There’s something generous in that type of filmmaking–no anger, just disappointment, with the lingering melancholy that nobody’s actions in life are perfect.

The Salt of Tears premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival.