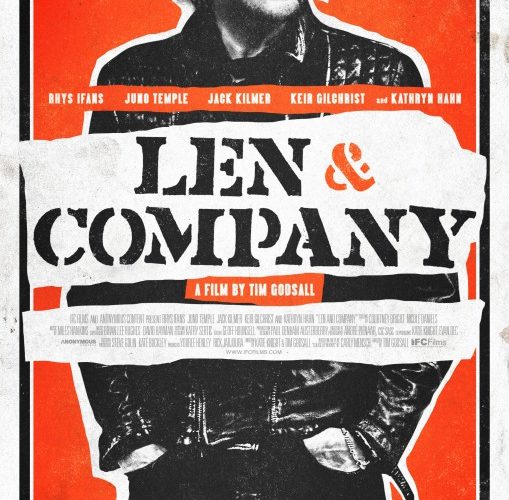

Hearing how deeply a film touched its cast lends a certain air that might not normally be there. Len and Company has it as Juno Temple and star Rhys Ifans both exclaimed during their TIFF premiere Q&A how affected they were by director Tim Godsall and cowriter Katherine Knight‘s script. Shot at the former’s own home with a delicate touch of humanity, an abundance of humor, and the perfect pinch of dramatic gravitas, the film proves more than its conventional story presumes. We’ve seen its depiction of mid-life and quarter-life crises—many times with the music industry at its back—but this newest iteration possesses an authenticity rendering it worthwhile nonetheless.

Ifans’ titular Len Black is the big persona at its center, a larger-than-life mythical creature of rock and roll producer clout who’s found staying in the background more suitable to his work ethic than actually performing on stage. Like most legends of a drug and sex-fueled era, his marriage to Isabelle (Kathryn Hahn) dissolved and his son (Jack Kilmer‘s Max) is an afterthought. So when the boy ends up in his backyard, Len automatically assumes it’s for a handout since being a father could never be a viable option. Max does want something, but it isn’t about money or even an industry referral. He wants to know Dad’s opinion about his demo—as a parent, not a cutthroat ass.

But that is pretty much all Len is. Just ask his family or his latest cash cow in international star Zoe (Temple). His relationship with the latter started years previously and he helped make her into a paparazzi magnet of bad choices and worse timing. God forbid he show her an ounce of paternal care too. Interestingly enough the one person he does show compassion towards is a neighbor boy named William (Keir Gilchrist) who works as his quasi-superintendent doing odd jobs around the house. The irony of this surrogate son is not lost on his biological one.

It isn’t long before the trio of misfits is under one roof with William playing fourth wheel on the outside looking in. Max is desperately trying to connect with Len despite his ambivalence and Len is attempting to toughen his son up by badly introducing some spontaneity to his otherwise “privileged.” Zoe enters as a devil’s advocate forcing the awkward silence between father and son into the open while also clinging to the hope Len might treat her like a human being for the first time in forever. And to think, this was supposed to be the producer’s much-needed respite of solitude.

There are many honest moments of drama that make Len and Company stand out from the pack. Some nice humor helps too—like the absurdity of William’s high school teacher allowing a loose cannon like Len to speak to the class. Godsall does a great job letting these scenes breathe without a need to tie everything together with a bow. This is a commendable and effective task, but it isn’t without problems. Zoe entrance, for example, arrives via sharp cuts to a venue far from Len’s house—disjointedly jarring transitions that confused me immensely. I was relieved when everyone finally got under one roof.

We do need these short glimpses into Zoe’s life to understand her struggle in the limelight, but the fact the others enter the frame in context with Len and she doesn’t is odd. It plays like she will be of equal importance to Ifans’ lead when she’s actually on the level of Max as a secondary. Her crisis is more attuned to the elder Black than his son, though, and that helps enhance the disparity between them. Max has had it a helluva lot easier than his Dad, but that blame lands on Len. His success made it so Max didn’t experience the depravity that makes rock and rollers and he can’t fathom the kid may have the goods regardless.

Things get dark in ways you’d expect a behind the scenes look at the music industry would. Depression and insecurity rule the day—even William joins the club with an affecting bit of turmoil perhaps unnecessary if Len’s heart to heart was directed towards Max instead. But then the way things are left between the Blacks wouldn’t be as effectively real or awkwardly laconic. Len can’t be the father he should, but he might learn how to be the father Max needs. And perhaps pushing William away helps him discover this after facing just how lonely he’s become. Everyone will get by without Len, but he truly needs them all.

Kilmer is good in his role and does bear a striking resemblance to his father Val. It’s a natural, instinctive performance that exists as a reactionary force to Ifans unpredictable Len. Gilchrist is a perfect mix of frustration and innocence while Temple’s a firecracker able to turn her smile from genuine to sarcastic on a dime like always. She contrasts Kilmer’s sheepish demeanor to hit Len from both sides—strong and soft. And Ifans excels at combating both with his lifeless stupor jolted by electricity when the occasion warrants. I felt the film had about four possible end points, but his consistently entertaining performance made any false alarms forgivable.

Len and Company premiered at TIFF and opens on June 10.