In the recent decades of Hollywood exporting slapped-together “children’s movies” to appease parents just looking to take their kids to anything that can pass the time, any film with an actual sense of youthful wonder in cinema feels like a lost artifact. For his directorial debut Riddle of Fire, director Weston Razooli creates such a utopia, following a group of mischievous children who embark on a woodland odyssey to deliver a pie, battle a witch, outwit a huntsman, befriend a fairy, and become best friends forever.

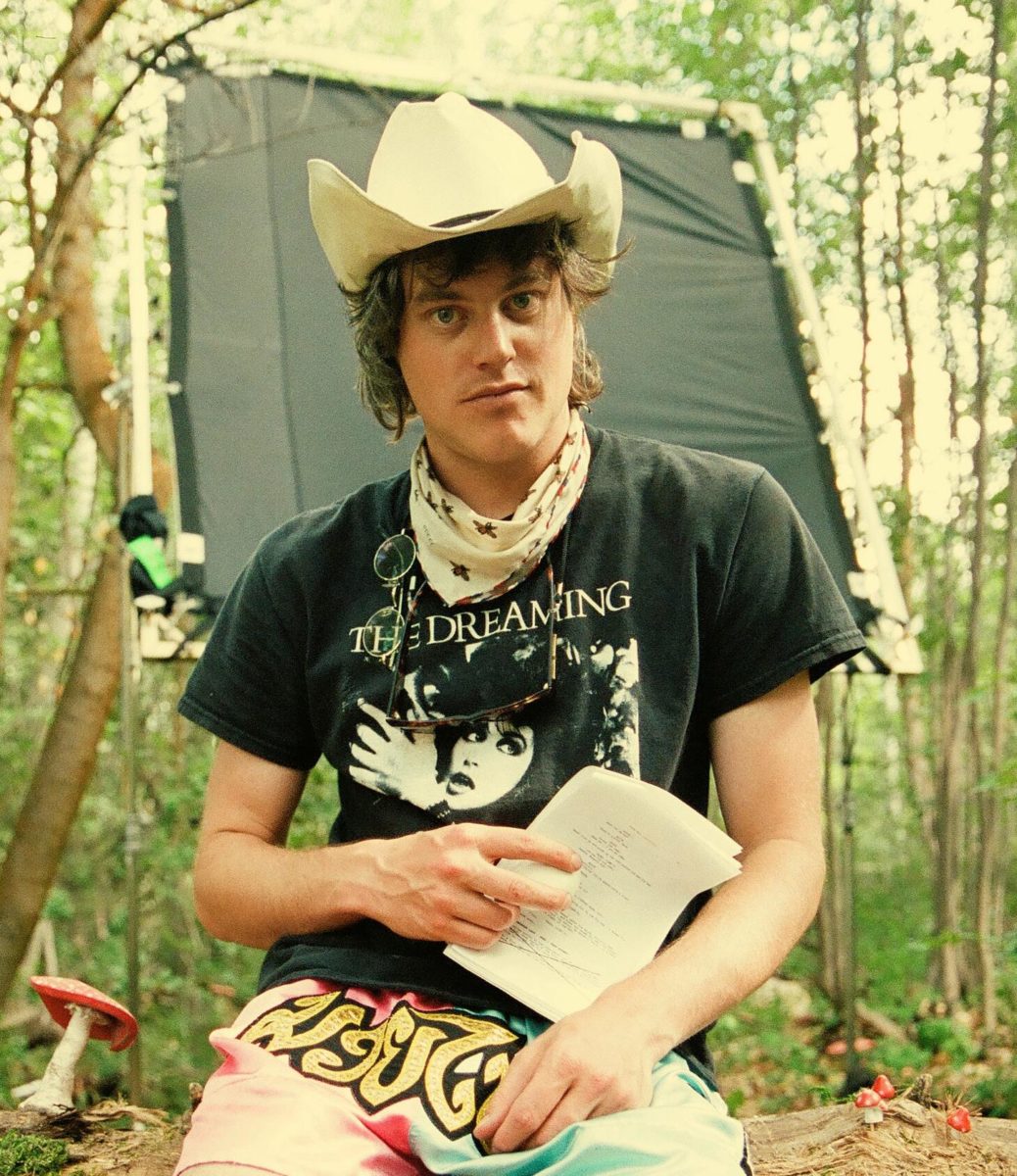

Though filmed in the Sundance headquarters of Park City, where Razooli grew up, the film premiered at Cannes Directors Fortnight last year and stopped by TIFF Midnight Madness. Ahead of the theatrical opening this Friday, I spoke with Razooli about capturing his neo-fairytale set on 16mm, being influenced by Hayao Miyazaki and Zelda, finding the right tone, what it was like working primarily with child actors, learning from bad movies, and more.

The Film Stage: When watching this film, there’s this sense the kids themselves could have directed it, which I mean in the best way possible. There’s a childlike wonder at play. How did you find the right tone?

Weston Razooli: Well, thank you. It’s a combination of things that I love now and loved as a kid. It was sort of me almost recreating my childhood, but a sort of fairy tale version of that. I also wanted to make it the ultimate kids movie where these kid characters have everything that you would want as a kid––like dirt bikes, paintball guns, the freedom, beautiful woods to adventure and explore. They’re sort of the masters of their own world. They’re sort of the chaotic, neutral goblins in the society. So they kind of wiggle around everything. They fight. They steal and do whatever. So they kind of live on their own. They live by their own moral codes, like pirates or something. And to me, it’s a childlike kind of vision of living and a way of life. That’s how I kind of live a little bit too. And it’s what I like and have always liked.

Also, it’s a lot of combinations of films I loved when I was a kid––like older Disney, like Davy Crockett and some anime, like early Dragon Ball, and a bit of Home Alone. It’s kind of a gumbo of childhood, dreamlike things and then the childlike direction of it came down to: I did want it to be very simply visually told for the framing and camerawork. I just wanted very basic framing as if I was almost working in cel animation or something to kind of contrast the craziness and amount of stuff that’s in the world. I want my world, characters, dialogue, and story to be loud, but the filmmaking is generally pretty simplistic and a little bit slapdash. That also came down to the time. The production every day was like a super rush. I mean, two to three takes because of the time that you have to shoot with kids every day. It’s very short.

You’ve mentioned you were in spurred by the Game Boy Zelda games and even the joy of split-screen Halo, which I also spent endless nights playing. Did you revisit any of those and, with anything you revisited, was it surprising to see how it aged now, as an adult?

So all the stuff that I love the most I still do. I love it still. Even the Zelda Game Boy games and the first Halo is still a great game, but there was a film that I watched because when I was sort of prepping for it, I was rewatching a ton of movies with kids that I loved and grew up loving. And in the ’90s there was a little bit of a boom with Little Rascals, Dennis the Menace, Home Alone, and The Sandlot. Then there was the unknown, terrible movies. There was one called Slappy and the Stinkers, and it starred some of the Little Rascals and it was about these kids who rescue a sea lion from a zoo and take it home. And my brothers and I loved that movie so much when we were kids. And I rewatched it and I was pretty horrified and scared. I was like, “Okay, yeah, directing kids could be very hard and very tricky.” You learn so much more when you watch bad movies, I think, because you’re like, “Oh, okay.” And you start seeing everything. Because watching perfect movies, you learn a lot, but sometimes they make it look easy. But if you see bad movies, it’s like, “Oh, wow.” So that specific movie––yeah, it was like, “This is genuinely scary.”

That process––working with the kids––did you know your approach from day one, or did it evolve over filming?

That’s a good question. A bit of both. It definitely evolved over filming, but my approach at first was: I wanted to keep it very simple. After I cast them I sent their parents some influences––very, very few. Maybe, like, two movies to watch for their specific character. And I was like, “Just watch, it’s sort of in the realm of the character, hope you enjoy it. But you can watch it and you forget it or whatever. It’s not like I want you to emulate it.” We never rehearsed because, with kids, I think once they get a scene they’ll just do it that way over and over and over again. And I didn’t want that to happen. Plus, there was very little time to rehearse anyways.

But basically I got pretty lucky with the kids I cast because they were pretty much the characters. My approach was, aside from a few things, mostly very simple. For example, if they’re emoting too much, I’m like, “Pretend you’re sleepy.” Sometimes they wanted to emote too much and I had to turn them down. For example, Charlie Stover, I was like, “Your character’s sort of been in the sun all day, so he’s a little tired and sleepy.” One of the things that evolved was: I invented a point system because the kids, after you cut, they want to run around and look at all the camera equipment and stuff and they don’t reset. So I created this game of points where whoever resets the fastest will get a point. And then, at the end of the day, whoever has the most points will get a treat––like a prop from that day of shooting. So that was pretty essential. That was very helpful.

When it comes to the locations, you mentioned recreating your childhood a bit. Are you going to places you explored as a kid or finding new locations? How do you think your knowledge of the locations aided the landscape of the film?

Yeah. I mean, every location has a huge story, and I would say that 90% of the locations are very important places that I grew up in. The forests are the forests I grew up exploring. The supermarket is the supermarket I grew up shopping at and it’s a supermarket where I shot so many short films there in high school with my friends. To shoot my first feature in this market was perfect. And then the A-frame house was the most special thing for me because it was this house that I always saw from a super-long distance up on this ridge, high up in the mountains. As a kid we drove past it and I would look way out at it and I would wonder who lived there and what they do and fantasize about this magical life that you would have to have to live in such a cool place. And when I was scouting I drove past and I was like, “I’m just going to go out there see what’s the deal.” It was a very long process to get that location, but we did get it and it really felt like the magical center of the entire film. And it was a great, great location.

The humor’s integrated quite well. It feels playful without ringing overly cute or sentimental. How did you approach that aspect?

The kids, I just wanted them to take it very seriously. But you’re right: it’s sort of a fine line of balancing the seriousness, the cuteness, the preciousness, the humor, and everything. And that’s where––in these types of films––when you start going overboard with anyone, that’s when they can really crash. So it’s difficult to balance all that.

It related to the different subtitles and different language elements you have throughout. How did you kind of develop that and talk to the kids about that?

So with the subtitles with Jodie [Skyler Peters]––that was never planned. When I cast him I didn’t really realize that he wasn’t as understandable as I thought. And then, the first day of shooting, he was incoherent. I was panicking, but the problem was: he was a great, hilarious kid. At the end of that day I had the idea, luckily, “What if I subtitle him? It would be hilarious and it’ll work.” The magic spells: I don’t know if I ever planned to subtitle them, but a lot of my work is very designed. I studied illustration and graphic design at art school, and so my movies have a ton of titles and graphics and motion graphics and posters and labels and everything. So I just went full speed ahead with everything. The magic spells was also to clarify they were saying a different language, not like you misheard something. And all the subtitles and all the graphics really play into this kind of board game, Game Boy game feel to me.

Shooting on 16mm adds such a great timeless texture to it. Can you talk about how you came to that decision versus going more digital considering the video game feel?

I’ve shot on 16 a bunch. Many, many music videos and a couple of short films, and I always wanted to make Riddle on 16. I’m showing a very stylized world and a world of fantasy with weird humor and weird characters. And for me to pull that off, shooting on film is the glue, the magic butter that holds it all together and allows you to accept the world as stylized. I personally don’t like sci-fi or fantasy or period film shot digitally. I can’t really give into the suspension of disbelief. I use the metaphor of film and digital: if there’s an outfit of clothing, there’s one person who can pull this outfit off and there’s one person who just can’t pull it off. And that’s film and that’s digital. It’s my opinion, but that’s that. Also, I just do love film. I think it looks super-beautiful and the idea of shooting a vintage fantasy-type kid movie on 16mm just sounded like a really epic, nostalgic, piece of magic that I was trying to make. It just felt like the way to go.

I saw this film at TIFF, which also screened The Boy and the Heron. I know Hayao Miyazaki is one of your favorites. It was cool you were both in the same festival. What does he mean to you as a filmmaker, and what specific influence did he have on this film?

I also saw The Boy and the Heron at TIFF; it was the only other movie I got to see there. He’s my favorite filmmaker for sure. I actually haven’t really connected that Riddle and a Miyazaki film were in the same festival. It’s cool. Yeah, he’s a major inspiration and influence. Essentially all his movies are super-influential, but specifically for Riddle I definitely wanted a Princess Mononoke vibe to the forest and the Anna-Freya character. When I was talking to Lio Tipton I showed her Lady Eboshi from Princess Mononoke. I wanted Anna-Freya to be like Lady Eboshi meets Sarah Connor from Terminator 2. For Alice (Phoebe Ferro), the two movies I sent were Paper Moon for Tatum O’Neal’s performance, I wanted that angstiness. Then I also sent Mononoke for San––her kind of angsty action, almost violent-like personality. I wanted that to be the thing for Alice.

With Miyazaki, obviously I’m doing my own thing, but I hope to capture this elemental spirit that surrounds nature and humans and relationships, everything. Also, I’m really into aviation and airplanes and stuff, and I will be eventually making a big airplane movie, and Porco Rosso was the film that got me into planes. I could go on forever but, yeah: Boy and the Heron, I thought it was an incredible, incredible piece of art. I tell people you should experience it as a dream and just accept it as a dream. I’ve only seen it once, so I’m eager to see it again. I loved it very much.

Riddle of Fire opens on Friday, March 22.